Tribe, Livelihood, and Change: Bedouin Sedentarization in Egypt

“The land that has raised you is like your father, whose hair seems black although he is gray.”

– Bedouin Proverb

It was during researcher Clinton Bailey’s decades with the Bedouin tribes of Sinai and the Negev that he heard this proverb. Proverbs, like poetry, are one of the oldest and most sincere expressions of Bedouin culture in history. This is a proverb expressing the love that the Bedouin people have for their home, for their livelihood, and for the desert. Bailey explains the proverb from his perspective, having heard it first hand from his Bedouin friends and research subjects, “Just as a child does not notice the blemishes of his father, such as gray hair, so Bedouin ignore the defects of their regions, which, though arid, have sustained them as a father sustains his children.”[1] The desert is their home, and their bond to it is powerful. While they love their home, and while it is a seemingly unmovable part of their culture, only 5% of Bedouin are still nomadic today[2]. This begs the question: if the Bedouin are so in love with their desert life, then why have 95% of them abandoned it? There are really only two possible answers. The first is that the Bedouin are simply no longer in love with the desert lifestyle, though, none of the academic literature supports this explanation. The second, and far more likely, explanation is that something with a great force must have compelled the Bedouin to abandon their nomadic lifestyle and become sedentary or semi-sedentary. This, however, is clearly not an adequate explanation in its own right. Something must have caused a great shift in Bedouin society and culture over the last years, decades, and centuries; the question is what.

For the Bedouin people, the intersection of culture and tradition illuminates their identity. In Hobsbawm’s and Ranger’s The Invention of Tradition, the authors provide an excellent theoretical framework through which we can approach the sedentarization of the Bedouin in Egypt. They describe what they call “the invention of tradition,” which can be understood as the process by which peoples forego practices they have employed in their history for any number of reasons and replace them with new practices, sometimes taking on the mantle of tradition as though they had always been so. While explaining when we can expect the invention of tradition within a people, Hobsbawm and Ranger claim:

[W]e should expect it to occur more frequently when a rapid transformation of society weakens or destroys the social patterns for which ‘old’ traditions had been designed, producing new ones to which they were not applicable, or when such old traditions and their institutional carriers and promulgators no longer prove sufficiently adaptable and flexible, or are otherwise eliminated: in short, when there are sufficiently large and rapid changes on the demand or the supply side.[3]

This explains almost perfectly what it is we have witnessed in the Bedouin culture over the last few centuries. Their circumstances supported a particular way of life; when their circumstances changed, however, it necessitated the abandonment of that way of life in exchange for a new one. It would be an egregious error and completely ahistorical claim, however, to suggest that the significant changes in Bedouin life and the accompanying sedentarization are a result solely of modernization post-World War I, as some may first think. In fact, historian Reuven Aharoni suggests “there is evidence that [sedentarization] existed in the seventh century, when the tribes entered Egypt in the wake of the Arab conquest.”[4] Thus, this work is not intended to explain the ultimate origins of sedentarization of the Bedouin people. It is also not intended to explain the history of an entire people or region, a nigh impossible task in less than several volumes. It is intended, rather, to examine how the unique socio-economic and political circumstances in Egypt from the reign of Muḥammad Ali through the post-World War I Arab world affected and accelerated the sedentarization already occurring in Bedouin society in Egypt.

Definition of Terms

The Bedouin are not a single, unified group – rather a collection of social groups, or tribes – which were created, dissolved, joined together, and split off over millennia in Egypt and the wider Middle East. In order to understand this distinction, however, it is important to understand just what the term ‘tribe’ means. As Aharoni suggests, there is no widely accepted definition of tribe. The tribe is a number of things simultaneously, including “an administrative division of the state and an organization that controls a home territory.” It “possesses political organization, tribal values and various ways of influencing society; indeed, it may be said that as a collective unit it possesses a cultural essence.”[5]

There are various competing theories as to what constitutes a tribe. The two main theories relevant to this work’s purpose claim that the tribe is centered around either politics or social stratification. Emanuel Marx puts the first theory forth in his edited volume, The Changing Bedouin, in which he claims that the tribe is primarily a political organization. The tribe and membership in it is defined by belonging to a common patrilineal descent group which is recognized as part of the tribe. The individual’s or group’s belonging is outwardly displayed by their place in the tribal genealogy. This descent group is organized for the common protection and advancement of the social, political, and economic interests of the tribe around a powerful individual or group of individuals in leadership positions. Using this framework, then, the leader or leaders advance the agenda of the tribe, which is shown to be primarily a political entity.[6]

The second theory is discussed by Aharoni on the basis of Phillip Burnham’s theory of spatial mobility. “This phenomenon,” Aharoni says, “influences the structure of tribal society, leading to the development of political centralism and social stratification.”[7] As competition develops both within and without the tribe, the strong will inevitably rise above the weak in social and political status within the tribe and the larger tribal confederation — defined as a collection of tribes working together, often temporarily and within territorial boundaries, for the common social, economic, and/or political benefit of those involved. A number of forces must be taken into account when tracking the development of tribes and tribal confederations of the Bedouin. Aharoni suggests that “climate, pasture, the neighbouring tribes and the government dictate the type of political organization, its size and the extent of the territory which it must control. In other words, tribal organization is based on territory, and adapted to its ecology.”[8]

Perhaps the best way to understand the use of the term here is to look at its Arabic language counterpart. According to The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, the Arabic word for tribe that the Bedouin would use – ‘ašīra – comes from the three letter root ‘ayn-shīn-rā,’ which, in one of its uses, means ‘to be on intimate terms with, to associate with one another, to live together.’ In other forms this root also refers to an intense companionship, a friend, or a comrade.[9] If we bring this understanding and those postulated by Marx, Aharoni, and Burnham together, we can see that in both the academic literature’s main use and this work’s use as well, the tribe is a social, cultural, economic, and political grouping, often centered around a common line of patrilineal descent, simultaneously concerned with both its internal and external relations and power dynamics that is equally as complex as any other group that inventive geographies might deem more ‘modern.’ The relationship of the tribe to the state is of paramount importance here. Aharoni’s examination of this relationship is one elegant and comprehensive enough to warrant its reiteration. He states:

As ‘stateness’ changes, the state incorporates tribes in various degrees of social integration and political participation. The tribes, on the other hand, have different degrees of autonomy and subordination. Thus, tribes and states create a dialectical symbiosis. They are simultaneously interdependent and separate….In the case we are discussing, the state was not created by tribes, and the bedouin did not play a significant part in its establishment and construction. Therefore, our study deals not with the transformation of tribes into states, but the dialectical symbiosis of the relations between tribes and the state over a period of time.[10]

Defining the term ‘Bedouin’ poses, perhaps, an even bigger challenge than tribe. It is again useful here to go back to the original Arabic etymology. The Arabic word for Bedouin, badawī, also badw, comes from the Arabic word for desert, bādiya, which literally casts a Bedouin as a person of the desert.[11][12] However, it is not sufficient to imply that Bedouin are Arabs who live in the desert, especially when attempting to find a working definition for academic purposes. Because the term Bedouin has never referred to a unified political or economic entity, and because Bedouin is not a separate ethnic group from Arab, the term Bedouin here refers to Arab nomadic and semi-nomadic groups whose livelihoods were drawn from animal husbandry and dry seasonal farming as they migrated through the deserts following the seasonally-changing resources as well as to those modern day, often sedentary Arabs who owe their lineage to said groups.

At different times in history Bedouin in Egypt were represented to the state and other actors by different ‘front men,’ as it were. Shēkhs would rise and fall, as would the individual tribes and tribal confederations that they led. As the influence of these shēkhs and their confederations would ebb and flow over the years, the political and social landscape of the Egyptian Bedouin would change drastically. From one period to the next an entirely new set of Bedouin would be the dominant tribal force in the region. Consequently, one cannot approach a historical study of Bedouin the same way one would approach a study of a state or ethnicity. While a state or ethnicity has a relatively constant historical representation easily traceable in the historical record, tracking a way of life is far more challenging. This difficulty is compounded by the fact that the Bedouin were largely unlettered until the middle of the twentieth century.[13] Consequently, all the available literature was written by non-Bedouin, and consists of ethnographies, chronicles and travelers’ accounts.[14] As though tracking a way of life amongst disparate groups was not difficult enough, tracking said way of life purely through the accounts of outside observers makes it even more difficult.

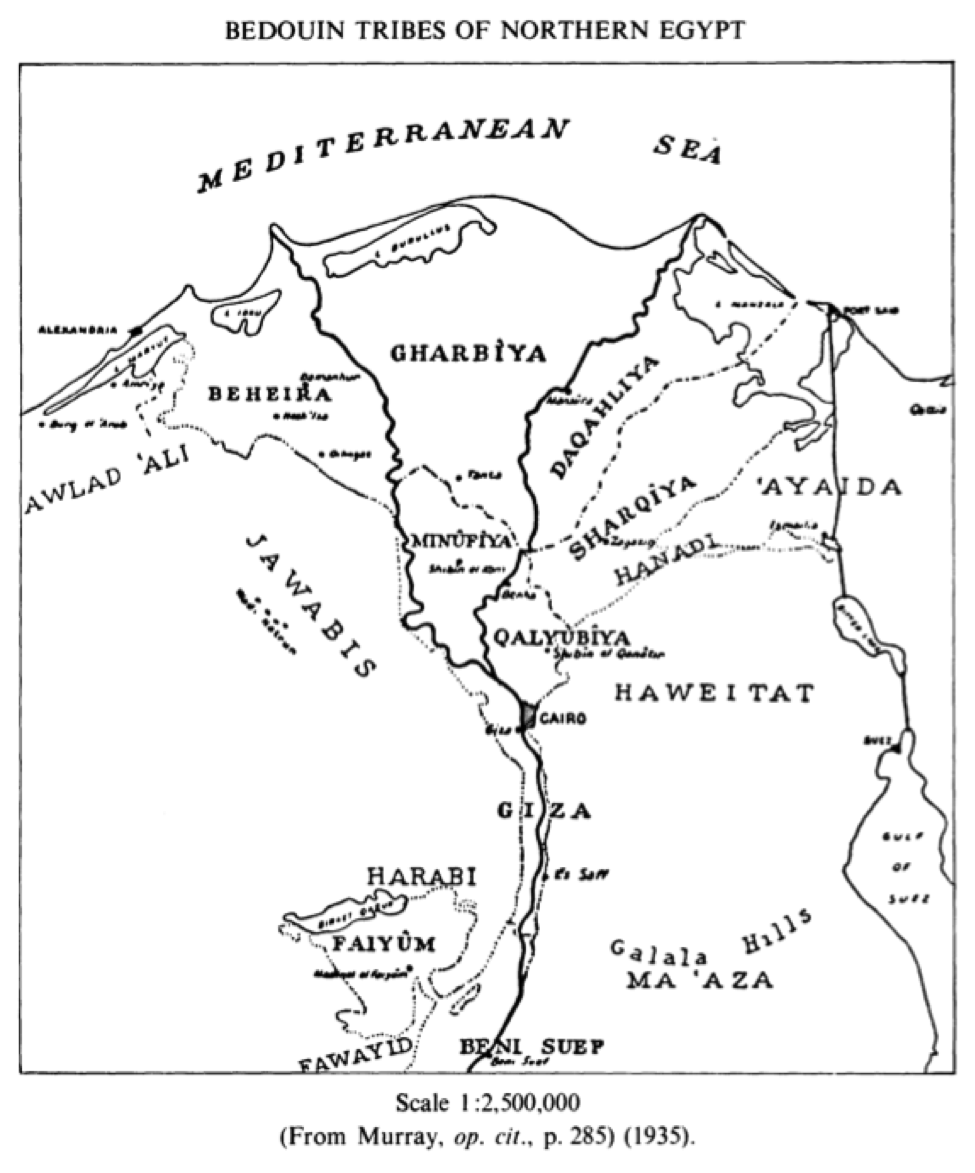

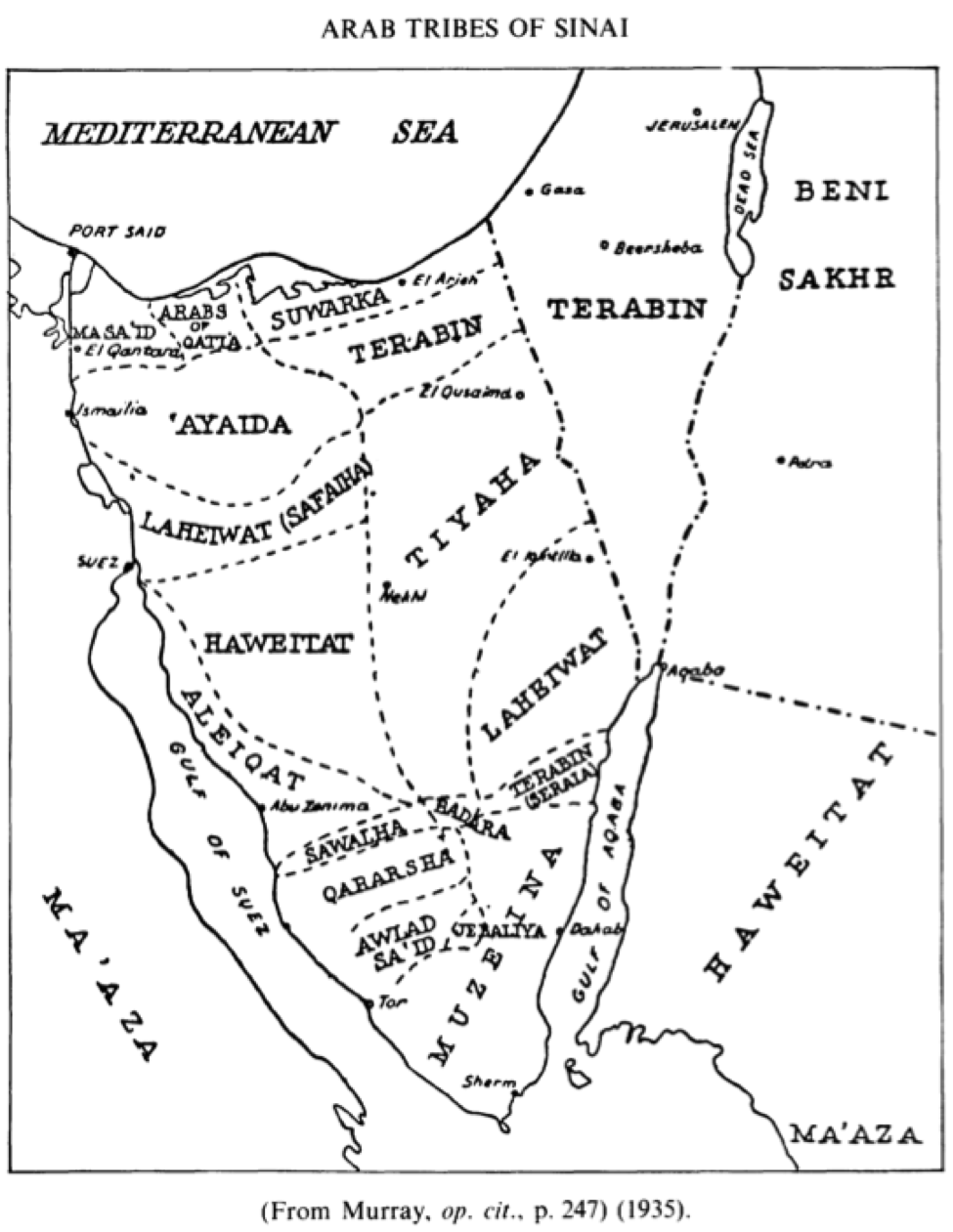

Since the rise and fall of different shēkhs and their tribes was the norm amongst Bedouin for so many centuries, one cannot simply say Bedouin and assume that word means the same thing now as it did in 1300 CE. Entirely different groupings of Bedouin exist at different points in history throughout Egypt and the Middle East. This is a result of “the unstable social structure of the tribes, and of the basic attribute which characterized Bedouin society: division and reunification.”[15] The diverse distribution of Bedouin tribes in Egypt at merely one point in time can be seen in the maps below, illustrating how difficult it is to explain the socio-economic and political circumstances of Egyptian Bedouin as a whole. Consequently, though many Bedouin groupings have experienced similar circumstances at certain points in history, each composition of Bedouin at different times may have different explanations for the socio-economic and political changes that have occurred in their society. Thus, it is imperative here to examine each grouping and time period individually while simultaneously attempting to draw connections and a historical continuity amongst these groupings over time.

From the Past to the Present

Bedouin are often typified as the archetypal Arabs: long before the advent of the state in the Middle East, they formed the backbone of Arab society. With the advent of Islam, a newfound organization brought the Arab Conquests to Egypt and the Bedouin tribes along with them. From that point until the reign of Muḥammad Ali in the 19th century, there was a relatively constant flow of Bedouin migration into Egypt.[16] Prior to the acceleration of sedentarization under Muḥammad Ali, and continuing through that period, Bedouin were nomads wandering the desert upon camels seeking pasture and pillage, left to their own devices and only rarely called upon as conscripts in the armies of the Egyptian rulers of the time. Today, though, the picture is much different.

The 95% of Bedouin who have become sedentary or semi-sedentary have taken up jobs in industry and the security forces, as farm workers, self-employed tractor and truck drivers, commuting wage laborers, and migrant laborers. Though many still practice the traditional occupations of herding and farming, many either abandon these in favor of more permanent employment or receive their primary income from their permanent employment while the Bedouin livelihood is either supplementary or held in reserve.[17] Their wage labor positions, however, are precarious, as Bedouin workers are seen as more expendable than sedentary, non-Bedouin workers, thus leading to deflated wages and the possibility of dismissal at any time, even after years of employment with the same business. Many of the Bedouin who do remain with their pastoral livelihoods have adopted a large-scale, more industrialized method of herding. They raise herds in large numbers, claim use of particular feeding grounds, hire help, and employ certain industrialized machinery, crafting a new group of capitalist Bedouin herders.[18] There is a distinction from tribe to tribe as to which jobs are typically taken up by Bedouin outside the traditional Bedouin livelihood, depending on where the tribe settles, what work is available, the ease of access to urban centers of employment, and their previous economic experience as pastoralists, seasonal agriculturists, and so forth. Bedouin of every tribal affiliation tend to settle in nucleated villages where they are close to water, shops, health services, and transportation. The majority of the time the settlements are either spontaneous creations of the Bedouin themselves or they join already established communities in urban and suburban settings. Only rarely, such as a few particular groups of Bedouin in the Negev, are they settled in government-sponsored settlements or suburbs.[19]

Marx argues in his essay that some nomads leave their tribes permanently, and that the range and frequency of nomadic movements have become limited, but he also shows that pastoral nomadism continues and that the tribal framework does remain intact to a certain degree. The four general trends that he sees amongst the pastoral nomad Bedouins today are:

- Nomads who have taken up employment in towns congregate in tribal residential enclaves and tend to concentrate in a limited number of work places.

- They maintain strong ties with kinsmen who remain in tribal territory, and many even keep their homes and families there.

- Even where few of the nomads still rely on pastoralism for a living, corporate descent groups remain intact and tribal territory is protected.

- They raise small flocks and till land in the tribal territory, even though they may lose money on these ventures.[20]

Through these general trends, one can see that there is no black and white distinction between what is a nomadic Bedouin and a sedentary Bedouin. Rather, sedentary refers to a Bedouin or tribe that is largely settled in a particular place and pursuing as their primary livelihood permanent employment in a business or industry that allows or demands that they remain in a singular location throughout the year. Within the term sedentary there is a further distinction between sedentary and semi-sedentary. While some nomads achieve a large measure of economic security in their sedentary lives and break away from their tribes, kinsmen, herds, gardens, and even their tribal friends also settled around them, essentially abandoning their Bedouin identity altogether, this is not the majority. The majority, Marx argues, are in fact closer to semi-sedentary. Unable to achieve a permanent foothold in the economic world of sedentary Egypt, they hold onto a “basic economy” in their tribal areas, which can be called upon and transformed into a subsistence-based economy with the help of the tribal relations, which they left intact in the case of failure in their more permanent economic life.[21]

Accompanying the contemporary sedentarization of the Bedouin is an increased government presence and control in all Bedouin affairs. More and more the Bedouin in settled communities are being absorbed into the same legal framework as other Arabs. An increase in police presence in settled Bedouin communities also brings government power deeper into the tribal structure as they are subjected to the same laws and restrictions as other sedentary Arabs. Furthermore there is a massive change in education amongst Bedouin youth that accompanies sedentarization today. When before youth in Bedouin societies would be put to work and learn the Bedouin desert livelihood, those in sedentary communities now attend schools and more and more are becoming educated professionals. Though uncommon, a handful of Bedouin doctors, lawyers, social scientists, and army officers are seen in Egyptian society and beyond.[22]

Along with more permanent and stable sources of income has come the ability to purchase, rent, and operate industrial machinery, adding to the abilities of Bedouin to participate particularly in the new industrialized agriculture of the sedentary population. With closer ties to government, law enforcement, industry, agriculture, and education we also see an increase in access to health care and social services, leading to an increase in life expectancy and birth rate.[23] Bedouin have, over the last several decades, participated in organized labor, becoming members of unions and participating in wider industry-labor relations.[24] Across the board it is apparent that Bedouin are now more closely tied to wider Egyptian society than they have ever been. This is very much to the liking of state governments throughout the Middle East, including Egypt, as it gives them a more firm sense of control and security in an area historically outside their grasp.

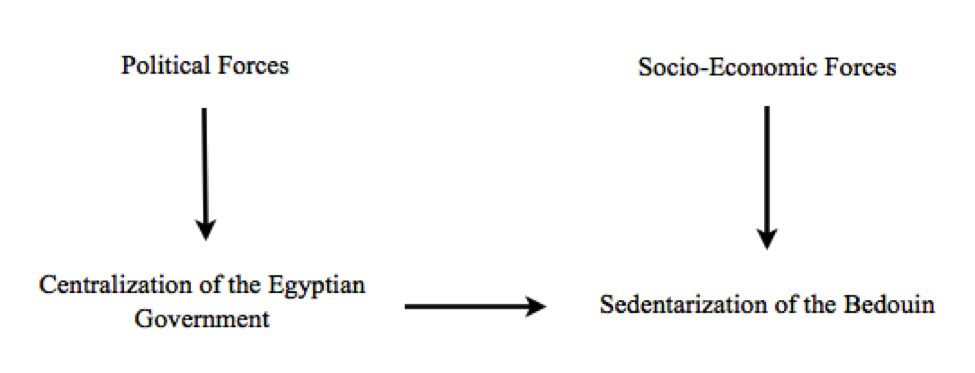

Having now seen where the Bedouin were, and where they are now, it is imperative to explore how they got there. The theme that will be seen here is that there is a strong connection between various forces at work in Egypt and the sedentarization of the Bedouin. Below is the flow of forces in effect, wherein socio-economic forces lead directly to the sedentarization of the Bedouin, political forces lead to an increased centralization of the Egyptian government, and, subsequently, the increased centralization of the Egyptian government accelerates further Bedouin sedentarization.

From Muḥammad Ali to 1914

Many of the changes in Bedouin society that have occurred over the last few centuries began or were accelerated under Muḥammad Ali. Prior to his rule, Egypt was largely undisciplined. Therefore, after his accession, he instituted vast reforms in every aspect of Egypt, including land distribution, labor relations, and military conscription. His reign was the first to see a significant increase in centralization of the Egyptian government, and the effect on the Bedouin was noticeable.

One of Muḥammad Ali Pasha’s first reforms – intended to create a revenue stream for the European-style state that he envisioned for Egypt’s future – was the nationalization of land throughout Egypt. This measure was a part of Ali’s central process, the process of nation-building. Through his new taxation policies, Ali seized much of the land belonging formerly to the multazims — tax farmers — and was free to redistribute the land as he saw fit.[25] Ali, however, exempted the Bedouin from many of his new taxes as well as forced military duty in exchange for their services.[26] Ali recruited and later appointed many Bedouin shēkhs to serve his purposes, one of those main purposes being the provision of Bedouin men for his military needs. After Ali Pasha’s accession to the throne in Egypt, the Ottoman soldiers available for his army were lacking. Thus, he needed the help of the Bedouin shēkhs to bolster his ranks, and the shēkhs provided desperately needed horse and camel-riding cavalry. In exchange for Bedouin protection of roads and trade routes in the largely ungoverned desert regions, he rewarded these shēkhs with land grants from land that had been seized from the multazims.[27] The now powerful landowning shēkhs established small iltīzam communities of their own around their new land grants, often bringing their families and kin with them, resulting in accelerated sedentarization of some of the Egyptian Bedouin in favor of a new livelihood.

This new aspect of the relationship between Ali Pasha and the shēkhs resulted in much closer supervision of the Bedouin communities in Egypt. Though the Bedouin were largely exempted from the compulsory service and taxes levied on the fallāḥīn – rural farmers – this close supervision led to a reduction in the power of the Bedouin tribes as a strong independent element.[28] As part of his plan to gain more control over the outlying desert areas and bring the Bedouin further under his control, Ali aimed to limit the territory from which they could derive their livelihood through his reshuffling of land distribution and control over the shēkhs. He also knew how to exploit the Bedouin’s need for allies in the outside world in the face of desert life and a changing political landscape. His attempts were largely successful, as he did establish in Egypt the closest thing there had ever been to a centralized European-style state, and his policies had a heavy effect on the Bedouin. The result of his policies toward the Bedouin was a decline in the profitability of nomadism and, thus, in the spirit of Hobsbawm and Ranger, a shift away from their nomadic tradition for some. At the same time, however, sedentarization is a very long-term process, thus, most of the Bedouin still remained nomadic even under his policies.[29]

After his death, Muḥammad Ali’s policies remained largely in effect under the rule of his successors, including, most notably, Isma’il Pasha (r. 1863-1879). Further attempts to incorporate the Bedouin into sedentary Egyptian society were made, however, under the Khedival leadership in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Isma’il, at one point, contemplated revoking the Bedouin exemption from forced military service and the corvée, but ultimately a distinction was made between sedentary and nomadic Bedouin, where only sedentary Bedouin were forced to pay the fee in lieu of the corvée.[30] In 1882, the Egyptian legislature even offered 7 of the 125 seats in the majlis to the large Bedouin tribes in an attempt to incorporate them without the use of force.[31] Later in 1882, a general census was conducted which attempted to count, along with the other Egyptians, the Bedouin within the Egyptian province. The numbers did not include the Bedouin who migrated across borders, because they were not considered real Egyptians, and thus the numbers make sedentarization look far more progressed than it actually was at the time. The 1882 census counted 245,779 Bedouin (about 3.6% of the population). 21,313 had reportedly given up the tribal environment altogether and were permanently settled in urban, suburban, and rural centers, although still regarding themselves as Bedouin, given that they answered to Bedouin in the census. 126,270 inhabited 822 Bedouin villages, of which 467 contained less than 50 Bedouin individuals and which still had a significant population that remained mobile during the year, and 98,196 were living in mobile tents.[32] Even if these numbers were wholly accurate, it would still be apparent that sedentarization of the Bedouin in Egypt had not yet entered full swing. The moderately paced sedentarization of the Bedouin resulting from an increased presence of the Egyptian government in tribal life and the socio-economic changes brought by it continued largely uninterrupted until the massive shake up in Middle Eastern political divisions that was World War I.

From World War I to 1952

By the time World War I had arisen, Egypt had been under significant British influence for several decades since the British military victory in 1882. Under Isma’il Pasha, Egypt had become increasingly dependent on the British, particularly after the completion of the Suez Canal when the British absolutely had to ensure a stable and friendly Egyptian leadership, and the 1882 conflict brought full de facto British control over the province. During these decades Egypt was still nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, but after the outbreak of World War I and the Ottoman Empire’s alliance with the Central Powers, the British formally expelled the Ottomans and established a British-controlled Sultanate. With this new form of British rule over Egypt came a new round of political centralization and socio-economic change.

During the occupation and control of the British over Egypt, the nation developed into a regional commercial and trading hub. The number of foreigners looking for work and investment in Egypt rose from 90,000 in the 1880s to over 1.5 million in the 1930s.[33] These foreigners became a large part of a new local industrial and commercial bourgeoisie that used resources of private wealth to diversify and invest in the Egyptian economy.[34] As a stronger British-led liberalization of the Egyptian economy came to be, the demand for and organization of labor in Egypt increased in urban, suburban, and rural settings. The continued industrialization of every sector of the Egyptian economy and the decrease in demand for the products of the nomadic lifestyle — i.e. protection of roads and trade routes, a reserve supply of conscripts, small and irregular supplies of animal products, etc. — led to the sedentary or semi-sedentary life being far more appealing economically and socially to the Bedouin.

There was a significant decrease in the government need of the Bedouin over the decades in that Muḥammad Ali Pasha and the Ottoman leaders before and after him were heavily reliant on Bedouin conscripts for their cavalry and infantry ranks. This necessity meant that they could not afford to completely discount the wants or needs of the Bedouin within their borders. In the decades following World War I, the need for an effective horse or camel riding cavalry and Bedouin foot soldiers greatly diminished, particularly since the British had no place for them in their regular army. This had a profound impact on Bedouin relations with the Egyptian state and British colonial masters after the war. This shift in military technology illustrated that the Bedouin were no longer much of an asset to the state and mandate governments, greatly reducing their obligation to tend to Bedouin needs. As a result, the Bedouin drifted into the hazy background of local public thought, along with the memory of their ancestral tradition of honor and self-reliance.

With an increased emphasis in Egypt on business and entrepreneurism, particularly in urban centers, and a decrease in the profitability of the nomadic way of life, it was around this time that the trend of Bedouin working and staying in towns and cities to work while maintaining families and small subsistence economies in the tribal territories began to take hold.[35] As under Ali in the 19th century, the British-dominated Egyptian government instituted policies that de-facto redistributed the land to industry and agribusiness based on liberal business accumulation, limiting the availability of land, and thus the availability of pasture and livelihood, to the Bedouin. Faced with no other options, scores of Bedouin were forced to find permanent or semi-permanent wage labor positions outside the tribal territories, only leaving behind a meager Bedouin existence, if they retained any ties to their kin at all.

From Gamal Abdul Nasser Forward

While entrepreneurial policies contributed to the limiting of Bedouin livelihood and subsequent sedentarization in the post-World War I period, the realities of Egypt after the 1952 revolution were very different. As John Waterbury argues, Egypt went through two modes of accumulation and growth. The first mode, he claims, was the initial efforts at import-substitution industrialization and protective tariffs from after WWI through the Depression that led to the aforementioned dispossession of land from the Bedouin during that period. The second mode, he claims, was initiated almost immediately by the military regime that took over in 1952. This mode consisted of state-led import-substitution industrialization and the state involving itself directly in the design of the economy under Nasser’s socialist regime. “This was a period,” says Waterbury, “of deepening and of developing vertical linkages in the industrial sector.”[36] Along these lines the trend of increased government centralization and socio-economic incentives for sedentarization continued.

The extent of cultivated land increased by nearly one third under Nasser’s policies, and unemployment and inflation were at record lows during the 1950s and first half of the 1960s.[37] These facts pushed the Bedouin further from their desert livelihoods and into the labor market, as their pasture was increasingly lost to them and the appeal of more stable sedentary and semi-sedentary life increased.

Under Sadat’s regime following Nasser’s death, a new direction that Waterbury calls “controlled liberalization” took hold in Egypt. Under this system, Sadat actually took some decentralization measures in the economy, but he and his government still held significant control over the lives of everyone from fallāḥīn to the landowning capitalists to the entrepreneurial elite, which continued to impact the fate of the Bedouin as it always had.[38] Under controlled liberalization, the rate of industrial and agribusiness control over land and resources continued apace, and sedentarization of the Bedouin continued in parallel.

The construction of the Aswan Dam also had a moderate effect on the Bedouin, just as it did every other Egyptian. The dam brought about many new jobs, but also displaced tens of thousands of people, providing economic incentives for Bedouin to settle in the face of severely disrupted lives. The backed-up floodwaters created a new micro-ecosystem around which some Bedouin began to become semi-sedentary. With new fertile, yet fragile, land to cultivate, some Bedouin took up agro-pastoralism around it, creating a new livelihood for themselves.[39]

A number of socio-economic factors since the first days of Nasser and Sadat, factors both old and new, contributed to accelerated sedentarization. One that had a huge impact was the widespread availability of motorized transport. According to Chatty, most Bedouin tribes were using motorized transport by the 1970s.[40] This newfound mobility amongst the Bedouin that got started slowly in the years before Nasser and then blossomed by the 1970s enabled the Bedouin to pursue a widely diversified set of economic pursuits to a more efficient degree. Cars and trucks served as transportation to and from centers of employment, instead of traditional camelback. They also could bring water to herds and transport livestock to markets, bringing the Bedouin deeper into the local economy.[41]

Another important factor, one that the Bedouin have had to deal with for centuries but was exacerbated by the new land restrictions placed on them by government and business policies, was droughts. According to Kathleen Galvin:

[There are] two major causes of change in pastoral systems. First is fragmentation, the dissection of a natural system into spatially isolated parts, which is caused by a number of socioeconomic factors such as changes in land tenure, agriculture, sedentarization, and institutions. Second is climate change and climate variability, which are expected to alter dry and semiarid grasslands now and into the future.[42]

Fragmentation we have seen amongst the centralization and entrepreneurial policies from Ali to Sadat, but climate change and climate variability is a factor that has a massive direct impact on Bedouin livelihood. The only way in which Bedouin can successfully roam the desert is if they have constant access to water. Both their livestock and the Bedouin themselves must drink, and any sort of seasonal farming they toil on requires seasonal rains to garner a fruitful harvest. In times of drought their livelihood is decimated, and they must find alternative sources of income and resources. Sometimes these alternatives are only temporary, but in recent decades the socio-economic factors that drive sedentarization lead most Bedouin affected by drought to become sedentary or semi-sedentary for the long haul. Hobbs and Tsunemi show us that, historically, severe droughts, such as the one that stretched from 1997 to 2005 in Egypt’s eastern desert, compelled Bedouin to settle permanently along the Nile Valley, or to take up wage labor positions in urban, suburban, and rural settings. One group, however, the Khushmaan Ma’aza Bedouin, responded to the drought by creating semi-sedentary tourist stations where tourists could come experience ‘traditional Bedouin life’ for a few hours.[43] When asked, the Bedouin said they would return to their desert livelihoods if the rains returned, but they, along with countless other Bedouin, have been forced into sedentary and semi-sedentary lives due to the combination of ecological and socio-economic change.

Conclusion

Today many Bedouin are nearly indistinguishable from any other Arab driving a truck, selling wares in the market, or working in industry or agribusiness. Employing the theoretical framework of Hobsbawm and Ranger, we can see that increased centralization of the Egyptian government over time and extreme socio-economic changes throughout Egypt have all contributed to a loss of Bedouin desert-dwelling tradition in exchange for a new tradition that is more suited to their circumstances. Looking at the state of Egyptian Bedouin today and their sedentary or semi-sedentary lives as shown by Marx, we can see how they have, over several centuries, taken these changes and incorporated them into their lives and livelihoods. The Bedouin are a hardy people, and though some might argue that their way of life is inevitably doomed, they always seem to find a way. Their livelihood will never be the same, and certainly a continued trend of a loss of Bedouin identity will continue, but the Bedouin will be around and a source of study for probably many years to come.

References

Aharoni, Reʼuven. The Pasha’s Bedouin: Tribes and State in the Egypt of Mehemet Ali, 1805-1848. London, UK: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Al-Khatib, Mahmoud A. “The Arab World: Language and Cultural Issues.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 13.2 (2000): 121-25. Taylor and Francis Online. Web. <http:// www.tandfonline.com/toc/rlcc20/13/2>.

Bailey, Clinton. A Culture of Desert Survival: Bedouin Proverbs from Sinai and the Negev. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2004. Print.

Chatty, Dawn. From Camel to Truck: The Bedouin in the Modern World. New York, NY: Vantage, 1986. Print.

Cole, Donald Powell. “Where Have the Bedouin Gone?” Anthropological Quarterly 76.2 (2003): 235-67. JSTOR. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3318400>.

Hobbs, Joseph J., and Fujiyo Tsunemi. “Soft Sedentarization: Bedouin Tourist Stations as a Response to Drought in Egypt’s Eastern Desert.” Human Ecology 35.2 (2007): 209-22. JSTOR. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/27654182>.

Hobsbawm, E. J., and T. O. Ranger. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1983. Print.

Galvin, Kathleen A. “Transitions: Pastoralists Living with Change.” Annual Review of Anthropology 38.1 (2009): 185-98. Annual Reviews. Web. <http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.usc.edu/stable/20622648>.

Kressel, Gideon M. “Changes in Employment and Social Accommodations of Bedouin Settling in an Israeli Town.” The Changing Bedouin. Ed. Emanuel Marx and Avshalom Shmueli. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction, 1984. 125-54. Print.

Marx, Emanuel, and Avshalom Shmueli. The Changing Bedouin. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction, 1984. Print.

Marx, Emanuel. “Economic Change Among Pastoral Nomads in the Middle East.” The Changing Bedouin. Ed. Emanuel Marx and Avshalom Shmueli. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction, 1984. 1-16. Print.

Murray, G. W. Sons of Ishmael: A Study of the Egyptian Bedouin. London, UK: G. Routledge & Sons, 1935. Print.

Osman, Tarek. Egypt on the Brink: From Nasser to Mubarak. New Haven: Yale UP, 2010. Print.

Schölch, Alexander. “The Egyptian Bedouins and the ‘Urābīyūn (1882).” Die Welt Des Islams 17.1/4 (1976): 44-57. JSTOR. Web.

Solway, Jacqueline. “The Bedouin of Wadi Allaqi: Social, Historical, and Economic Perspectives.” Wadi Allaqi Project, South Valley University, Egypt. 33 (1999): Web.

Tignor, Robert L. State, Private Enterprise, and Economic Change in Egypt, 1918-1952. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1984. Print.

Vatikiotis, P.J. The History of Egypt. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1985. Print.

Waterbury, John. The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat: The Political Economy of Two Regimes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983. Print.

Wehr, Hans. “‘ašīra.” The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. Ed. J. Milton Cowan. Urbana, IL: Spoken Language Services, 1994. Print.

[1] Bailey, Clinton. A Culture of Desert Survival: Bedouin Proverbs from Sinai and the Negev. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2004. Print. 16.

[2] Al-Khatib, Mahmoud A. “The Arab World: Language and Cultural Issues.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 13.2 (2000): 121-25. Taylor and Francis Online. Web. <http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rlcc20/13/2>. 123.

[3] Hobsbawm, E. J., and T. O. Ranger. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1983. Print. 4.

[4] Aharoni, Reʼuven. The Pasha’s Bedouin: Tribes and State in the Egypt of Mehemet Ali, 1805-1848. London, UK: Routledge, 2007. Print. 13.

[5] Aharoni, vi-3.

[6] Marx, Emanuel. “Economic Change Among Pastoral Nomads in the Middle East.” The Changing Bedouin. Ed. Emanuel Marx and Avshalom Shmueli. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction, 1984. 1-16. Print. 12-13.

[7] Aharoni, 38.

[8] Aharoni, 38.

[9] Wehr, Hans. “‘ašīra.” The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. Ed. J. Milton Cowan. Urbana, IL: Spoken Language Services, 1994. Print. 718-719.

[10] Aharoni, 2-3.

[11] Wehr, 59-60.

[12] Bailey, 1.

[13] Bailey, xxi.

[14] Aharoni, vi.

[15] Aharoni, 19.

[16] Aharoni, 23.

[17] Marx, Emanuel, and Avshalom Shmueli. The Changing Bedouin. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction, 1984. Print. x.

[18] Marx, 1.

[19] Marx and Shmueli, x.

[20] Marx, 1-2.

[21] Marx, 2.

[22] Marx and Shmueli, xi.

[23] Marx and Shmueli, ix.

[24] Kressel, Gideon M. “Changes in Employment and Social Accommodations of Bedouin Settling in an Israeli Town.” The Changing Bedouin. Ed. Emanuel Marx and Avshalom Shmueli. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction, 1984. 125-54. Print. 130.

[25] Vatikiotis, P.J. The History of Egypt. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1985. Print. 55.

[26] Murray, G. W. Sons of Ishmael: A Study of the Egyptian Bedouin. London, UK: G. Routledge & Sons, 1935. Print. 31.

[27] Aharoni, 6.

[28] Aharoni, 6.

[29] Aharoni, 6.

[30] Schölch, Alexander. “The Egyptian Bedouins and the ‘Urābīyūn (1882).” Die Welt Des Islams 17.1/4 (1976): 44-57. JSTOR. Web. 46-47.

[31] Schölch, 48.

[32] Schölch, 49.

[33] Osman, Tarek. Egypt on the Brink: From Nasser to Mubarak. New Haven: Yale UP, 2010. Print. 33.

[34] Tignor, Robert L. State, Private Enterprise, and Economic Change in Egypt, 1918-1952. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1984. Print. 5.

[35] Cole, Donald Powell. “Where Have the Bedouin Gone?” Anthropological Quarterly 76.2 (2003): 235-67. JSTOR. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3318400>. 240.

[36] Waterbury, John. The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat: The Political Economy of Two Regimes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983. Print. 10.

[37] Osman, 57.

[38] Waterbury, 379.

[39] Solway, Jacqueline. “The Bedouin of Wadi Allaqi: Social, Historical, and Economic Perspectives.” Wadi Allaqi Project, South Valley University, Egypt. 33 (1999): Web.

[40] Chatty, Dawn. From Camel to Truck: The Bedouin in the Modern World. New York, NY: Vantage, 1986. Print. 119.

[41] Chatty, xxv.

[42] Galvin, Kathleen A. “Transitions: Pastoralists Living with Change.” Annual Review of Anthropology 38.1 (2009): 185-98. Annual Reviews. Web. <http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.usc.edu/stable/20622648>. 185.

[43] Hobbs, Joseph J., and Fujiyo Tsunemi. “Soft Sedentarization: Bedouin Tourist Stations as a Response to Drought in Egypt’s Eastern Desert.” Human Ecology 35.2 (2007): 209-22. JSTOR. Web. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/27654182>. 209.

Amazing write up! Thanks for this post