Introduction

In ancient Greek, Roman, and Egyptian civilizations, mental illness was viewed as a form of demonic possession or religious punishment. Mentally ill people were chained to walls and subjected to cruel and unusual treatments such as lobotomies or strange surgeries that more than often resulted in death. People did not understand the brain and mental illness at the time, so the mentally unstable were mistreated and locked away from the rest of society. These negative attitudes towards mental illness continued on into the 1700s in the United States, leading to the stigmatization of the mentally ill (Farreras, 2013). Currently, depictions of mental illness are present in the media, and studies show that they negatively influence the public’s perspective, while contributing to the stigma around mental illness (Kobau and Zack, 2013). For example, movies such as Shutter Island and A Beautiful Mind can affirm people’s misconceptions about schizophrenia and how the disorder affects a person’s life. This leads to a stigma against the disorder and mental illness in general. Similarly, movies such as Psycho and Hide and Seek are depicting dissociative identity disorder (DID) inaccurately and, in turn, influencing society’s perspective on it. Due to a lack of awareness, the misrepresentation of dissociative identity disorder in film is affecting society’s perceptions of this mental illness by creating a stigma that has led to the isolation of these mentally unstable individuals from the rest of society.

Overview of the Influence of Film

Film is a form of mass communication and has a very large influence on the perspectives of the audience and/or viewers. They become common experiences between people of different backgrounds and provide them with a way to come together and talk or learn about different issues that might otherwise be seen as “taboo” to discuss (Damjanovic, 2009). A study done by Michelle C. Pautz, an associate professor of political science at the University of Dayton, suggests that films are a huge influence. Dr. Pautz gathered undergraduates (ranging from ages 17-22) and asked them to fill out a questionnaire on their opinions on the government before and after watching movies having to do with government conspiracies. The results showed that after watching the films, 20-25 percent of the students changed their opinions (Pautz, 2015). This study shows how the representation of an issue in a movie shapes people’s attitudes, proving that film has the ability to influence the perceptions and opinions of the public. Film has the ability to cause people to affirm or reject their preconceived notions on a certain issue or subject.

An interview with the late Tom Sherak, an actor-producer who was president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the 2009-2010 term, further revealed how film influences society. He discussed how movies “take sides, remain central, or project something forward,” and create controversy depending on whether the audience agrees or disagrees with the content. Because movies are made by filmmakers who want to take a position on a topic, they often lead to conversation and debate. Further discussing the film industry, Sherak went on to explain that movies are something “[people] all have in common,” and that whether one likes the movie or not doesn’t matter (Shah, 2011).

Overview of Mental Illness/DID

According to the National Alliance of Mental Illness, a person with dissociative identity disorder (DID), known formerly as multiple personality disorder, “is characterized by alternating between multiple identities” (2016). It is one of a group of dissociative disorders, which are mental illnesses that involve “disruptions or breakdowns of memory, consciousness or awareness, identity and/or perception” (Cleveland Clinic, 2016). People with DID usually develop tens of identities, but start off with 2 or 3 alternate personalities that each have different backgrounds, mannerisms, and thoughts. DID is usually developed as a way of coping with trauma, and it usually forms in people who have experienced childhood trauma such as “long-term physical, sexual or emotional abuse” (National Alliance of Mental Illness, 2016). People create alternate personalities that don’t have the problem they are suffering from to cope with whatever is going on in their “real” lives. However, while there is no cure for this disorder, therapy and medication can aid patients in controlling their alternates by helping them all work together instead of against each other (Tartakovsky, 2016).

With its first known case in 1883, dissociative identity disorder is one of the earliest studied psychological disorders, and as more cases followed, books were published on the findings that came along with them. In 1895, physicians Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud published Studies on Hysteria, a book that described different case histories of several patients that showed dissociative symptoms, one of them being a patient known as “Anna O.” (Gillig, 2009). Anna O. had multiple personalities, which Breuer described as “two separate states of consciousness” where one state was normal and the other “insane” (Borch-Jacobsen). Her symptoms included paralysis, hydrophobia, lethargy, and language difficulties. Breuer observed Anna O., and categorized her disorder into four stages: latent incubation, manifest illness, intermittent somnambulism (sleepwalking), and recovery. These observations and conclusions furthered the psychoanalysis of dissociative identity disorder, as more psychological theoreticians and psychologists saw the observations and work of Breuer and Freud.

However, there is a large group of people in the scientific community that don’t believe that DID exists. There are many disorders that cause controversy or generate disbelief in the public, such as bipolar disorder or attention deficit disorder (ADHD), but they are noncontroversial in the mental health or medical community. DID is an exception, though. Dr. Charles Raison of Emory University calls it a “middle-of-the-road position,” and explains that every psychiatrist has his or her own opinion on dissociative disorders. Many psychiatrists or general practitioners say that this disorder doesn’t exist, and if it does, it’s “iatrogenic,” which means that “it is caused by therapists training their patients to interpret their symptoms as if they have a whole set of distinct personalities” (Raison).

However, there are other trained professionals, such as therapists, that specialize in people with this condition, and will set up meetings for each of the patient’s alternate personalities. They point out the fact that the patient’s different personalities have different electroencephalogram (EEG) tracings – which are tests or records of brain activity – for each one, while skeptics try to discredit this fact by saying that actors have the ability to produce different EEG tracings when they go into different characters.

DID exists on a spectrum, similar to most mental illnesses, from normal to pathological, and Dr. Raison asserts that it is “very common” for trauma victims to “manifest high rates of dissociation,” and DID is said to be caused by extremely traumatic events such as child abuse or sex abuse (“DID Medical Breakthroughs”). He concludes by saying that he doesn’t believe that people have multiple personalities existing in their minds, but that some people who have suffered trauma dissociate so bad to the point that “either on their own or as a result of therapeutic experiences” they deal with their experience as if it was happening to multiple, different people.

Link between Movies and DID

A paper on psychiatry and movies published in the Clinical Center in Serbia states that the movie transcends the theater, making the viewer totally preoccupied with the images and sounds (Damjanovic, 2009). Therefore, it represents the most influential form of mass communication, and movies such as Psycho and Hide and Seek, despite their worth in an artistic sense, encourage inaccurate, preconceived notions on dissociative identity disorder, and while there isn’t much specific research on the societal effects of the representation of DID in film, research on the influence of film and the misrepresentation of mental illness can be synthesized to fill any gaps.

Filmmakers often exploit certain stereotypes – negative, and in this case, untrue beliefs – of people with DID, such as violent or homicidal tendencies, not having any control over their alternate personalities, or not being aware of their different identities at all. Social psychologists believe stereotypes are “especially efficient, social knowledge structures that are learned by most members of a social group” (Corrigan and Watson, 2002). They represent notions of groups of people, and are efficient because people can quickly generate “impressions and expectations of individuals who belong to a stereotyped group” (Corrigan and Watson, 2002).” Stereotypes often lead to prejudice and discrimination against these groups and people and end with them being isolated from the rest of society.

Also, the causes of the character’s DID is almost never shown in the films, and mental illness is instead used as a storyline (Suzdaltsev, 2014). Movies continue to portray DID inaccurately, perpetuating stigmatization of those who have it. Some argue that movies only reflect society’s views on things, so they aren’t contributing to the stigma around mental illness, since they’re just showing how people actually feel about it (Lilenfeld, 2015). However, in a recent interview, Dr. Danny Wedding, a former director of the Missouri Institute of Mental Health and co-author of Movies and Mental Illness: Using Films to Understand Psychopathology, discusses how movies play up the more dramatic parts of mental illness to make for more interesting films, ignoring whether the symptoms of the character are accurate or not (Suzdaltsev, 2014).

For example, In Psycho, Norman Bates, the main character, is shown to disassociate into his mother by dressing in her clothes and talking to himself with her voice (Hitchcock, 1960). However, The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders states that one of the symptoms of DID is “recurrent gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and/or traumatic events that are inconsistent with ordinary forgetting” , so it would be unlikely for someone with DID to have conversations with an alternate personality (2000). Also, there is no explanation as to why Bates developed this disorder, but it is implied that Norman Bates and his mother were involved in an incestuous relationship.

In Fight Club (1999), the unnamed narrator dissociates into Tyler, a man that is completely opposite to what he is really like. By the end of the film, the narrator is “captured” by Tyler, and has to force himself to kill him and free himself from his alternate identity. This implies that the narrator doesn’t have control over his alternate identities, which is rarely the case with someone who actually has DID, according to the National Alliance of Mental Illness (2016). In this film, DID was used as a hyperbole to show what could happen to one if he or she continues to be oppressed by society, and the narrator is shown to have insomnia and low self-esteem, which are two things that don’t lead to one developing dissociative identity disorder.

In Hide and Seek (2005), the main character’s alternate personality is a violent and manipulative murderer. He is shown to not know about his disorder and goes on a killing spree without being aware that he is going into an alternate personality. People with DID are usually very lethargic and tired; they do not have the energy to do many things, much less kill people, so this movie is another example of an extreme and stereotypical version of someone with a dissociative identity disorder, contributing to the stigma around DID.

Shutter Island (2010), which was directed by Martin Scorsese, is set in the 1950s, a time when people were extremely uneducated and ignorant about mental illness. It’s about two US Marshals who travel to a criminally insane hospital on Shutter Island, and one of them is delusional. His condition isn’t stated anywhere in the film, but it is implied to be dissociative identity disorder. The psychiatrist in this film used electric shock treatments and lobotomies to cure him of his delusions. The fifties and sixties were a time when traditionalists believed shock treatment was the way to deal with mental illness, especially DID, while modernists believed that different forms of psychotherapy, education, and medicine were the ways to help mentally ill people. Scorsese toyed with the audience’s emotions, but it was reported that he had a psychiatric consultant, Professor James Gilligan of NYU, on set at all times to proofread the script, checking for accuracy (Clyman, 2010).

Lastly, in the movie Split (2017), James McAvoy stars as the main character who has twenty-three alternate personalities along with an animalistic twenty-fourth emerging, which is referred to as the “Beast.” His host personality, or original personality, has a therapist who talks about the disorder as a new form of evolution, instead of as a mental disease. McAvoy’s character kidnaps three teenage girls, and as his latest personality forms, he has a craving for human flesh and devours two of the three girls. This film shows alternate personalities to not only be violent and destructive but cannibalistic as well — which isn’t accurate at all.

Methodology Process

I have chosen to do a meta-analysis of the data available in literature and films to display the research on the societal impacts of the misrepresentation of dissociative identity disorder in film. I have conducted this method of research through a mixture of film analysis and a synthesis of information from articles about mental illness and the influence of film. Articles about the influence of film will support my claims on how the portrayals of people with DID are harmful to society, and scenes or lines from films will serve as examples of the misrepresentations of DID. I’ve been looking at films with an analytical lens, gathering my observations, and coming up with conclusions (original research) about the way the DID archetype has evolved through time as well as comparing actual scientific facts about DID to the way it is shown in movies to conclude whether or not the portrayals have gotten more accurate with the increasing amount of knowledge the medical and scientific community has attained from the 1960s to present day.

I have also incorporated a correlational analysis with the meta-analysis by analyzing different factors – such as medical advancements, level of education on mental disorders, and sensitivity to mental illness – that contributed to the evolution (or lack thereof) of dissociative identity disorder in films. However, due to the type of quantitative data that was available, I have mostly focused on the correlation between the portrayals of DID in film and the amount of medical knowledge society has regarding mental illness. I used information from medical articles, the NAMI database, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) to measure the amount of medical information on DID.

I thought about doing a survey that included clips of movies (i.e. Split) so people could watch them and give their opinions on DID before and after the clips. I planned on using this survey as another way of proving my claims, however, I have decided against it because I feel as if a qualitative approach to this project is best. There have been numerous studies done on the influence of film, and while there isn’t one on DID films specifically, I assume the results would be the same, and people’s opinions would be influenced by what they have just seen (taking into account how honest the participants were). Incorporating graphs from data I have collected is a more representative way of displaying the evolution (or lack thereof) of DID films over time. With this method, I didn’t have to worry about people being honest or answering questions thoroughly; I just had to look at facts, and figure out how to display them visually.

My project is focused more on how the representation of dissociative identity disorder in film has changed over time and why, instead of just seeing how the portrayals affect people’s opinions. Split serves as the “gap filler” in my research, since it is the most recent film, and I can use it to properly analyze how or if the portrayals of DID have evolved over time. It has been concluded in numerous studies and papers that I have cited that negative portrayals of mental illnesses contribute to the stigma surrounding them. Therefore, I did not find it necessary to test this theory out again. I focused on why and how this is the case with this particular type of illness instead of gathering data through a survey to answer my research question on the societal impacts of these misrepresentations.

My goals for this project were to connect the portrayal of DID in film to the stigma surrounding them and to report on society’s perceptions of DID and how it has evolved because the correlational analysis I have done connects the stigma to the portrayals of the illness in films, which I can use to analyze the evolution of society’s views on DID along with mental illness as a whole. There haven’t been many shortcomings during my research process except for the fact that DID films are not highly reported on. There are no specific studies on DID in film, so I had to use articles on the representations of any mental illnesses in film or just mental illness in general, since a lot of the time, the exact illness the character suffers from isn’t explicitly stated, it is implied or left for the audience to guess. Also, if I had a bit more time to conduct research I would have analyzed more films to properly report on the evolution of DID films throughout every decade, but I tried to pick successful, well-known ones from every other decade.

Original Research and Results

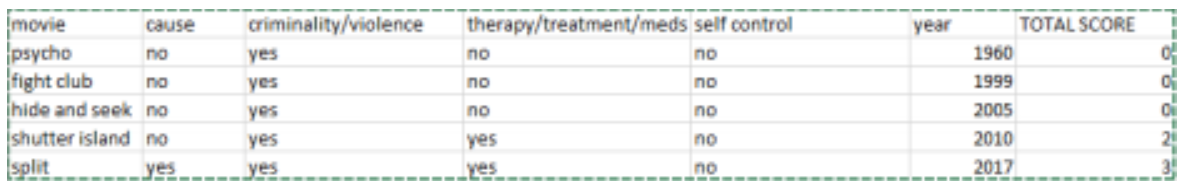

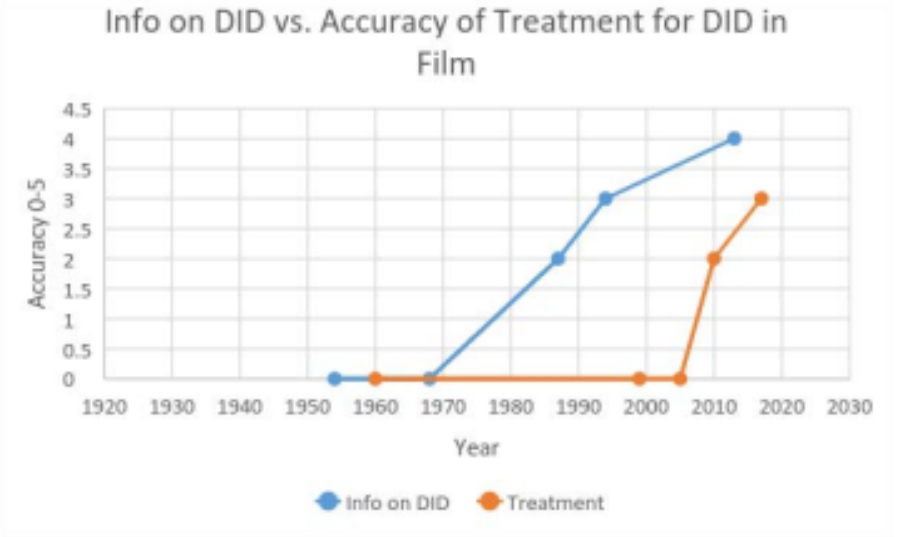

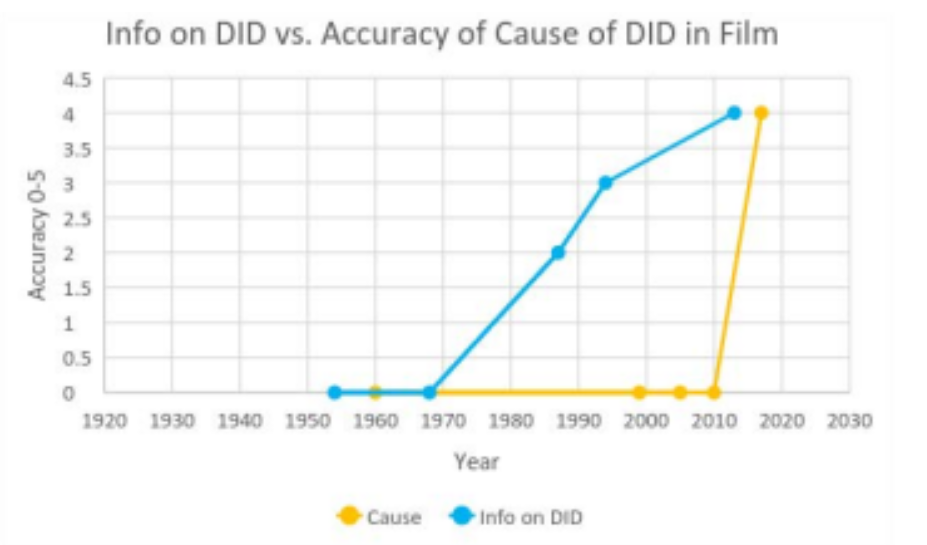

My original research involved displaying all the information I gathered with the meta-analysis (through watching films) with graphs to show the trends and evolution of the portrayals of DID in films. I put all the movies I had watched into a spreadsheet and decided on factors to “grade” them off: the presence of criminality and/or violence, the accuracy of the cause for the character’s DID (if there was one stated), the character’s self-control and awareness over his/her DID, and the presence of treatment (including medicines or any form of therapy). I graded each film based on these factors and gave them a score from 0-5, 0 being not accurate at all, and 5 being completely accurate as shown in Table 1.

Table 1  Then I proceeded to graph the overall accuracy of each film and the year it was released as shown in Figure 1.

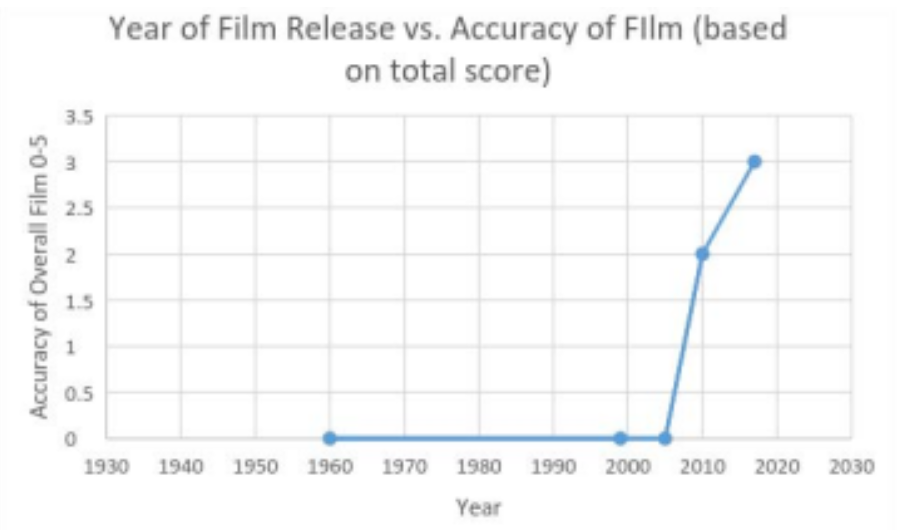

Then I proceeded to graph the overall accuracy of each film and the year it was released as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

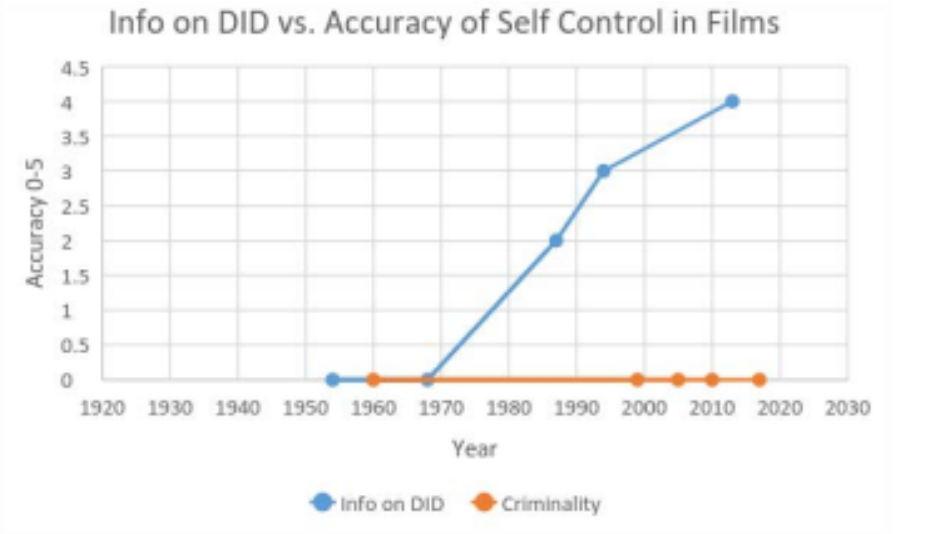

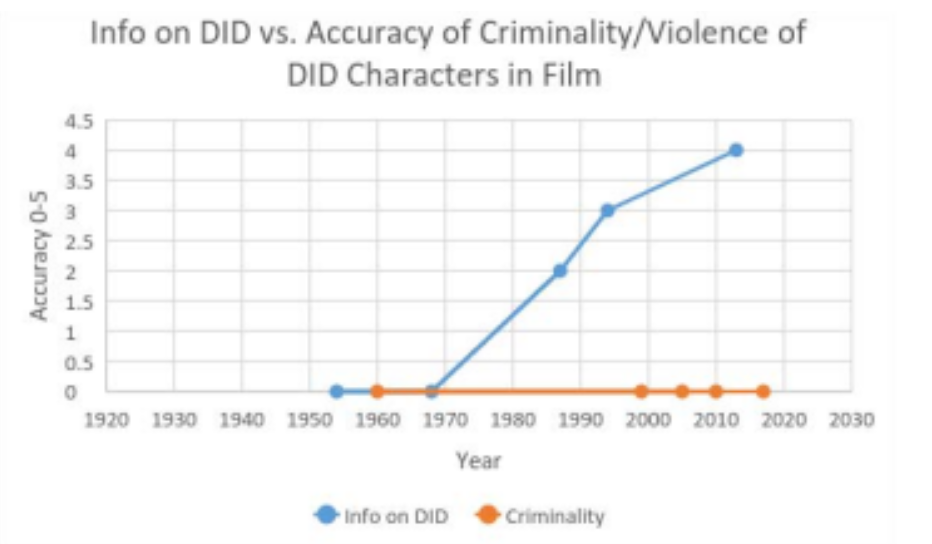

I noticed that as time went on, the portrayal of DID in films did get a little more accurate. After this, I needed to break down each factor and see how the accuracy of each of those changed, if they did, throughout time. Another thing I was analyzing with this project was whether or not the accuracy of these DID films increased with the amount of knowledge on the disorder. I measured this by reading the DSM manuals and giving them each a rating based on the amount of information present in each one. The first two, which came out in 1954 and 1968, respectively had no information on DID at all (0 on information scale). The third one (2 on information scale), which came out in 1987, had a small paragraph, but referred to it as MPD, which is a term no longer used to describe this disorder. The fourth and fifth editions (3 and 4 on information scales, respectively), which came out in 1994 and 2013, respectively had extensive information on it, and referred to it as DID, the proper term. I graphed the accuracy of each factor (shown in Figure 2, 3, 4, and 5) alongside the information on DID (0 being no information and 5 being extensive information) that was present at the time the movie was released.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

As shown by my graphs, the accuracy of the cause of DID and proper treatment for it increased over time with movies such as Split showing both the actual cause of DID and therapy, the most common form of rehabilitation for a person suffering from DID. However, factors such as self-control and criminality/violence stayed at a 0 with every film I watched and analyzed. This is due to sensationalism. Films are thought to be more interesting when the characters with DID are violent and criminal, even though that is never the case for a person who actually suffers from the disorder. The fact that the cause and treatment of DID are being portrayed accurately proves that society has attained a larger amount of knowledge on it, but because movie directors’ goals are to fascinate their viewers, they play up factors such as violence.

Analysis of Results

With the movies I have watched and focused my project around, it is evident that films dramatize the disorder – such as McAvoy in Split playing a man who suffers from DID and has cannibalistic, murderous alternate personalities – and incorporate inaccuracies for a more “exciting” film. These inaccuracies may be overlooked, but as stated in “How Movies Change Our Minds,” people who do not have prior, accurate knowledge on a topic are usually influenced by film whether they realize it or not. Negative influences contribute to the stigma surrounding not only dissociative disorder, but all mental illnesses, as well as other aspects of mental health such as therapy and medication. Movies such as Shutter Island and Split, the two most recent films in my research, portrayed accurate treatments and Split showed the cause of the main character’s illness, but they both still had elements of criminality and violence.

It is evident that films tend to blur the definition of mental illness and take creative liberties in making up symptoms for disorders or playing up the more aggressive, rare cases of them. Filmmakers often take inspiration from the stereotypes of mental illness, instead of the actual, scientific information about the particular illness. Organizations such as the National Mental Illness Association have dedicated themselves to fight and invalidate the misconceptions of DID along with other mental illnesses, while films often lead them to become even more deeply rooted in popular culture. Negative attitudes about mental illness are still very present among the general public, and films, being such an influential, pervasive form of media, have the potential to decrease them.

Consequences and Implications

Society’s perceptions and opinions of dissociative identity disorder are largely based on film due to a lack of education on the issue. Mental illness is not something everyone has knowledge on, so therefore, films that misrepresent it or portray it inaccurately cause a larger stigma around it, and contribute to the stereotypes and prejudice about the disorder and its symptoms. Also, mentally unstable people watching films that portray them as murderers, for example, can lead to them actually developing violent tendencies due to self-stigma, which is when one starts to form negative feelings towards his/herself.

If people are more aware and educated on what DID really is, the negative attitudes and stigma surrounding it would reduce and those suffering from DID or any mental illness, would not be ostracized from the rest of society. People who suffer from mental illnesses deal with the symptoms of their disease and also deal with the prejudice and discrimination that stem from the misconceptions about mental illness and health. An extreme form of discrimination would be social avoidance, where people refuse to interact with mentally unstable people at all, and this is already happening. Research has shown that this stigma towards mental illness has a harmful effect on “obtaining good jobs and leasing self-housing” (Corrigan and Watson). Due to this, mentally ill people often find it hard to live a normal, quality life, and while there is much more research to explain different mental illnesses in scientific terms, there has been little to no extensive research on the stigma surrounding it until recently.

Conclusion

Society has made advancements in terms of the amount of information it has on DID and mental illness, but this advancement is not translating into films. Due to sensationalism, films tend to dramatize or play up things like criminality and violence for a more “interesting” storyline. Films should include more aspects of what DID is actually like rather than just including the ones that would make for a more “interesting” film, so viewers of these movies can be more aware of what mental illness is really like, and there would less negative attitudes against DID and other mental illnesses.

Works Cited

Corrigan, Patrick, Amy C. Watson. “Understanding the Impact of Stigma on People with Mental Illness.” World Psychiatry, 5 January 2017. Web. Feb. 2002.

Clyman, Jeremy. “Shutter Island: Separating Fact from Fiction.” Psychology Today, 23 Feb. 2010. Web. 30 Dec. 2016.

“Dissociative Disorders.” www.nami.org. NAMI, 2016. Web. 11 Nov. 2016. “Dissociative Identity Disorder.” my.clevelandclinic.org. Cleveland Clinic, 2016. Web. 11 Dec. 2016.

“DID: Latest Medical Breakthroughs.” www.newsmax.com. News Max, 4 Oct. 2010. Web. 23 Feb. 2017.

Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel. “Bertha Pappenheim.” www.psychologytoday.com. Psychology Today, 29 Jan. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2016.

Damjanovic, Aleksandar, Olivera Vukovic, and Aleksandar Jovanovic.

“Psychiatry and Movies.” Psychiatria Danubina 21.2 (2009): 230-35. 2009. Web. 10 Nov. 2016. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Vol. V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Print.

Farreras, Ingrid G. “History of Mental Illness.” Nobaproject.com. NOBA, 2016. Web. 10 Nov. 2016.

Fight Club. Dir. David Fincher. Perf. Brad Pitt. Twentieth-Century Fox, 1999. DVD.

Gillig, Paulette Marie. “Dissociative Identity Disorder: A Controversial

Diagnosis.”www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Matrix Medical Communications, Mar. 2009. Web. 1 Dec. 2016.

Guida, John. “How Movies Can Change Our Minds.” Newyorktimes.com. The New York Times, 04 Feb. 2015. Web. 14 Nov. 2016.

Hide and Seek. Dir. John Polson. Perf. Robert De Niro. 2005. DVD.

Kobau, Rosemarie, and Matthew M. Zack. “Attitudes Toward Mental Illness in Adults by Mental Illness–Related Factors and Chronic Disease Status: 2007 and 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.” American Journal of Public Health103.11 (2013): 2078-089. Www.cdc.gov. CDC, 2013. Web. 1 Dec. 2016.

Lilienfeld, Scott O., and Hal Arkowitz. “Can People Have Multiple Personalities?” Www.scientificamerican.com. Scientific American, 22 Aug. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2016.

Psycho. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Screenplay by Joseph Stefano. Perf. Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh. 1960.

Raison, Charles. “Is DID Real?” CNN. Cable News Network, 23 Feb. 2010. Web. 30

Mar. 2017. Shah, Vikas. “The Role of Film in Society.” Thoughteconomics.com. 19 June 2011. Web. 12 Dec. 2016.

Shutter Island. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Perf. Leonardo Dicaprio. 2010.

Suzdaltsev, Jules. “We Spoke to a Psychologist about Hollywood’s Depictions of Mental Illness.” Vice.com. VICE, 21 Oct. 2014. Web. 24 Sept. 2016.

Tartakovsky, Margarita. “Media’s Damaging Depictions of Mental Illness. “Psychcentral.com. Psych Central, 17 July 2016. Web. 15 Sept. 2016.

Leave a Reply