by Jeremy Lambert

*

*

“Shit.”

He dropped the match.

“Shit,” he said again, snuffing out the tiny flame with a loafer.

Bud struck another one, lighting his cigarette with a faint crackle as he sucked in the smoke. He looked down at the previous one lying on the floor of his porch, right between his feet. The heat from it had felt good until the flame licked his finger. He held it up, inspecting the damage. He couldn’t tell if it was a burn—every bit of his skin was a fresh pink, thanks to the cold.

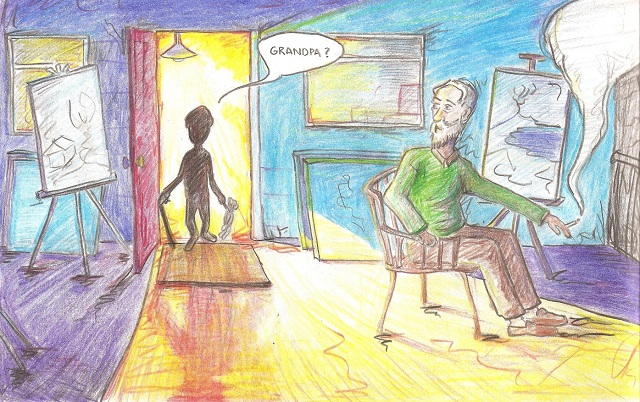

It was snowing. An easy one where the flakes shook down white and soft as dove feathers. He pinched the cigarette between his lips, rearranged the tattered afghan around his shoulders. The air felt cold and clean. Crisp. Refreshing. In this weather, walking outside was the same as plunging into fresh water. But when he took another drag the slow and relaxed process of blowing out smoke went stiff. His chest hardened as his lungs squeezed into fists. He was used to it. These coughing bouts never seemed to quit, lasting for minute on top of minute of jerking, ragged heaves. Then the blood came up—and there it was now—flecking his hand with those little red dots. When it stopped, he sat back in his chair, listening to the click of the old heater in the corner as it warmed. With a cough like this, no matter what he was doing he immediately looked vulnerable. Awkward and self-aware. He grabbed a corner of the afghan and wiped the blood off his beard. The porch was closed in by walls and windows but that didn’t stop the cold from getting in, and he was happy to have the heater—that’s why it was there—and he’d gotten used to listening to it like it was a radio. All around him, hundreds of canvases were leaned up against the walls. Landscapes and portraits. Most were finished with no place to go, waiting like colored dominoes. His easel lay in front of him, holding a blank one.

It’s funny. It looks so much like what hides behind it. Just another blanket of snow. That’s all it is, the canvas. Wet white snow.

The chair creaked as he shifted, his legs voicing their discomfort. He took another drag and poked his glasses, which immediately began inching down the bridge of his nose back to where they were. Between his fingers, the cigarette threatened to give his finger another burn, glowing down, smaller and smaller, as he watched. With the tiniest of movements, he let it fall into the tin can below. It used to be an old coffee can. Folgers. Once the coffee grinds ran out, it started holding his discarded butts and it smelled like death—or what Bud thought death might smell like. Burnt things and dirty water. The door behind him opened. He turned.

“Jim?”

The little boy stood in the open doorway, a warm encasement of amber light smoothed over the slopes of his silhouette. He was leaning on a cane.

“I heard something,” little Jim said.

“Heard what?”

“Something.”

“Oh, something,” Bud replied as he wrapped the afghan tight around his shoulders. He grabbed his own cane, leaning on his chair, and stood up. “Something’ll always want to bother you. Wake you up.” Bud walked over to little Jim in the doorway, placed his hand on his head. They walked inside together. “But you gotta tell it, you tell it: Mr. Something, I won’t be bothered tonight. No sir.”

Jim limped his way through the hall with his cane, and Edward shut the door.

“Now let’s get you to bed.”

***

He waited until little Jim was asleep. It didn’t take long. Then, leaving the door cracked, he made his way down the hallway towards his own room. The floor creaked with every step. He used to try and make a game out of it. When he was little he pretended they were mines. The floor creaked and BOOM—dead. He taught the game to Jim. It was good exercise for the kid. It was one thing to get a bum leg, Bud thought. A bullet to the thigh or something like that. But to be born with one? That’s a tough thing, and little Jim had had it all his life. Bud used to try and comfort him, called him Bud Jr. He’d play soldier with him, their canes becoming guns. POW POW! Bud would roll over, dead, tongue lolling out of his mouth. Then little Jim would come close, and Bud would come back to life and grab him.

It wasn’t as simple anymore. The kid was growing up. Every day he came closer to realizing the hand he’d been dealt. Unable to play sports, unable to dance at the school prom, unable to fit in. Bud didn’t know what else to do but delay it.

The door to his room was already open. He limped in. It was a nice room. Not huge, but lived in and comfortable. Soft carpet. Big bed. Fireplace. The fire had died some time ago. It always amused Bud, when building a fire, that it was always said not to throw stones in a glass house. What about fire in a wooden one?

He leaned on the cane, shifting his weight to the bed, half falling onto it. The cane landed softly on the carpet and he pulled the sheets close. Hanging on the cross next to his bed were tubes. He pulled them off with a shaking hand and wrapped them around his face, twisted the valve and oxygen came flowing in with a hiss. He breathed and breathed. The dying fire left a lingering smell of smoke. He sucked it in, the pure air and the tainted.

He knew, of course. Knew what he was doing. The withering lungs trapped in his body were beyond repair. But he had to have the oxygen on. It’s the only way to sleep. Otherwise the night was full of hacking and heaving. Blood, too.

He stared at the picture on the nightstand until he was asleep.

He woke what seemed like hours later, his face shoved deep down in the pillow. His glasses still on, almost glued to his face. The first thing he noticed was the silence. The hiss of the oxygen was gone, had ran out. His mouth was dry and his nose was hot. He lifted his head and his tired eyes opened to a squint. Dawn. An orange glow came in through the blinds. Dust floated down. No. Not dust. Snow. It was snowing in his room. He looked up and there was only white ceiling. He saw her when he looked back down. She was at the foot of his bed. Hair and dress from many years ago. Sadness seemed to be etched into the lines of her pretty face. She just sat there, motionless. Staring at him. Bud couldn’t move and the only thing that moved was the snow as it covered the room, the bed, the blanket. A tear rolled down his wrinkled cheek. He recognized her. She was in a photograph, the one that sat on his nightstand. Her name was Mary. And they were together for 52 years.

He hesitated, not knowing what to do. He felt so aged in that moment. Vulnerable and hooked to an empty breathing device. A tiny, frail body in a bed too big for it. Mary’s eyes remained fixed on his. The light from the window started to move. The shadows shifted on her face. Her eyes lost their starry glint. Something was wrong. The light kept moving, not much of it left. She began to shrink, skin stretching tight over her bones. Her ribcage sticking out, the skin pulled taught over it. Her cheekbones hollowed, face now a gaunt horror, eyes on him. The blackest eyes. He was helpless.

When the snow stopped, she was gone.

***

Little Jim was the first to wake the next day. He limped to the kitchen and knocked the Raisin Bran from on top of the fridge with his cane. Poured the cereal and milk in. Voila. Breakfast. He balanced the bowl in one hand and gripped the cane with his other, careful not to spill the milk on the floor. He sat down at the table, just as the front door opened. He looked up.

Claire stepped in, arms full of groceries. She saw Jim at the table and smiled.

“Morning sweetie. Where’s your grandpa?”

“Hi,” he said. “He’s sleepin. I’d talk to you more but I gotta eat my cereal. It’s gonna get soggy.”

Claire laughed, setting the groceries down on the table next to him. She moved a few stray blonde hairs from her face, squeezed little Jim on the shoulder.

“I understand completely. What’re you having little man?”

“Raisin Bran. It’s good. Not great though. But I do like the raisins,” he said, mouth full of cereal.

“Well luckily I got you some more Fruity Pebbles.”

He looked up from his bowl, smiling. She returned it, and started to unpack the bags.

Jim picked a raisin out of his bowl.

“Why are they wrinkly?” he said, staring at it.

“Wrinkly?” Bud said from the hall. “Not talking about me, are we?”

Claire’s head popped out from the kitchen. “Morning Bud.”

“Morning dear,” he said, sitting at the table.

“The raisins,” little Jim continued.

“Eh?”

“Why are they wrinkly?”

“Ah, them. Well, they used to be grapes, y’know. Then they got old. And they got wrinkly.”

“Oh.”

Claire walked back in from the kitchen. “He’s right, you know.”

Jim popped the raisin in his mouth, stared back in the bowl of old wrinkly raisins. Claire watched him, smiling. She looked over to Bud. “Are you good on oxygen? I picked some tanks up from work on my way over.”

“Hmm? Oh. I’m out actually. Ran out last night.”

She got up. “Not to worry, I’ll bring them in.”

“Thanks, dear.” He said as she headed for the door.

Jim grabbed his bowl, spoon swinging around inside, and got up from the table. He clutched it tight to his chest, using the cane to steady himself as he neared the kitchen. Bud looked around the room. On every wall there were at least two of his paintings. They were everywhere. These ones were old. Having them on the wall used to reassure him that he had accomplished something. And they still did. But the feeling had diminished some.

Claire came back inside, keys clanging off of the oxygen tanks she held. “Where do you want em, Bud?”

He turned in his seat to look at her, “Just there is fine.”

Jim walked over to her, cane in hand. “Hey, come see something.”

“Ok.” Claire looked back at Bud with a grin.

Bud smiled and followed.

Out on the porch were two easels—Bud’s canvas still blank and waiting, but there was a smaller one next to it. On it, in wonderfully childish blues, blacks, and greens was a landscape. Sky, trees, and grass. Jim pointed at it.

“That’s what it’s gonna look like when the snow melts.”

Claire smile grew, “Wow, you’re right! That’s exactly what it’s gonna look like.”

Little Jim beamed up at her. She pointed to the other one.

“And what’s that one gonna be?”

Jim looked at his grandfather, Bud’s old caterpillar eyebrows raised in anticipation. Jim turned back to the painting.

“Well, it’s already done,” he said. “It’s the snow.”

Bud laughed, and was immediately overtaken with coughs.

“Ah, yes,” he managed to say, wiping his mouth with a handkerchief. “One of my best efforts. Finally nailed the simplicity of it all.”

Claire buttoned up her coat, laughing. “They’re both great. Especially Jim’s.”

The boy beamed.

“Ok, I’m outta here. Anything else you two need?”

Little Jim looked up at Bud, who shook his head.

“I don’t think so.” Then: “Oh, tomorrow is snowman day.”

“Hmm?”

“Jim’s gonna build a snowman tomorrow, er,” he looked to the boy. “What was it?”

“Snow-deer. I saw one over there in the yard so maybe we can build him a friend.” Jim said matter-of-factly. Bud turned back to Claire.

“Well there it is. Snow-deer. Interested?”

Claire smiled.

“Couldn’t miss that, could I?”

She stepped back out into the cold and left. Bud shuffled over to the space heater, clicked it on. His grandson sat down on his little chair, in front of his little easel. Bud joined him.

“Not bad, James. Not too bad.” He started to unpack the paints by his feet. The boy started doing the same. “I gotta catch up to you,” he groaned, sitting back up, brush in hand.

They painted together, on the porch.

***

Bud woke with a sore chest. The night was full of coughs and not much else. He unwrapped the tube from his face. It was morning.

“Fuckin’ thing.” He threw it on the floor. He turned on the lamp next to his bed. His picture was face down on the desk and when he went to grab it, he hesitated, remembering why.

The boy was shouting. Bud’s sluggishness wore off instantly. He gripped his cane and, hauling off the bed, moved as fast as he could.

“Jim? Hold on. Hold on, son.”

His bare feet smacked the hardwood floor in the hall, creaking with every step. By the rules of his own game he would have been blown to smithereens by now. BOOM! BOOM! BOOM!

He shoved through the boy’s doorway.

Little Jim was asleep, lumped under his blanket, as still as a stone covered in moss.

“Jim?”

He turned to Bud, tired eyes opening.

“Pop?

“Nothing, I… It’s nothing. You were dreaming. Go back to sleep.”

Jim sat up.

“Pop, my Dad wore glasses, right?”

“Yeah,” Jim said, out of breath. “He did. Big embarrassing things.”

Jim took a moment. “What about Mom? Did she?”

“No. Why do you ask?” he said, leaning on the door frame.

Jim scooted to the edge of the bed, grabbed his cane from the post. “I was dreaming about them, I think.” He got himself up, PJ’s loosely hanging on his bony little frame as he limped over to the door.

“Yeah? What were they doing?”

“They were dancing. They were dancing in a big old room. Dressed up and everything.”

Bud tried to laugh, coughed instead. “Looked silly I would think. I raised your mother. Sharper than a rail spike, but I’ll be damned if she ever knew how to dance.”

“No. It didn’t look silly.” Jim walked out of the room. Bud followed, the floor creaking with each footstep. “It was a slow one. They were smiling. It looked fun.”

“Fun, hmm?”

“Yeah. We were the only ones there.”

They arrived at the kitchen. Little Jim first, balancing himself and knocking down a box of cereal from the top of the fridge with a whack of the cane. No matter how many times Bud placed the cereal within reach, the boy always made him put it back on top of the fridge. Another game for him to play. God knows the boy needs them in this boring old place, he thought. He grabbed bowls and spoons for the two of them. They sat at the table.

“Looked just like her mother, she did,” said Bud, grabbing the box of cereal and turning it upside down into the bowls. “Same way as you look just like your old man.” It wasn’t until Jim dug in to his own cereal that Bud noticed he had himself a nice big bowl of sugar-coated, rainbow colored flakes in front of him. Not exactly Raisin Bran, but what the hell. He spooned some up.

“Am I supposed to ‘taste the rainbow’ with these things?” Bud said.

His grandson laughed.

“Nope. These are Fruity Pebbles.”

He chewed.

“What’s the rainbow one?”

“Skittles.” Jim said, mouthful of cereal.

“Ah. Well these aren’t terrible.” He chewed more. “So. We building this snow-deer thing?”

Jim was halfway to the kitchen, when he whipped around so fast that the spoon flew right out of his empty bowl.

“Oh yeah!”

***

Bud couldn’t take the cold. Not like he used to, anyway. He was back inside the porch, half painting, half watching Claire and Jim finish off that snow-deer. Turns out Claire was a damn good sculptor. The thing almost resembled a deer. Almost.

Bud’s painting was starting to come together, too. He decided on just painting what was right in front of him, right through those porch windows. Tall, dark trees bereft of any signs of life clawed at the pale blue sky. The tiniest bit of green showed through the snow on the ground, a lone verdant sentinel checking to see if it was safe to come out again. Not yet, little man.

His fingers, stained with black paint, gripped the brush a bit tighter. He raised his head and peered through his small glasses at the canvas. Finishing up one final branch, he set the brush down and took off his glasses.

Well, it was a fat deer. That’s for certain. But not bad. They had just added the head. He could hear their muffled voices through the window. Claire, all bundled up with a warm knit hat to match, stepped back to look at it.

“Something’s missing.”

Jim picked his cane up and dusted the snow off it. He limped back to Claire, and looked back at their deer.

“It needs the prongy things.”

“Right,” she said, checking the ground. After a few minutes, two particularly gnarled twigs with branches shooting out in all directions were poked into the deer’s head, and there they were: antlers.

When Bud went outside to congratulate them, there was silence. They were gone. Nothing but the snow, sky and light, and then the sound of Jim’s tiny laugh. Bud searched the area from where the noise was coming from. Then, out of the frozen air, it arrived. A snowball. It spread across Bud’s face and dripped onto his shirt. Claire was laughing too. Then all three of them were laughing.

***

Jim was still outside, building friends for the deer. Claire had come back inside after the snowball fight. Little Jim won the bout, using his cane as a catapult.

Claire made hot chocolate. She popped her head out from the doorway.

“Marshmallows?” she asked.

“No, thanks.” he answered.

“Ok then, here we go.” She handed him the steaming cup.

“Cheers.”

Bud took a sip.

He looked over at Claire, still rosy-cheeked from the cold. She raised her eyebrows.

“And?”

“Excellent,” he said.

She turned back to watch Jim. “Good.”

He didn’t want to bring it up. He’d already tried to talk to her about it once before.

“Claire,”

“Yes?” Her eyes didn’t leave the boy out in the yard, limping about with his cane. Slow, through the snow. Not a care in the world on his tiny shoulders.

“I’m not exactly…getting any better over here.”

That broke her gaze. Bud regretted it.

“I just…I’m afraid I’ve made Jim a bit dependent on you and it’s not fair, what I’m going to ask.”

She understood. He could see it.

“I know,” she said. “You don’t have to ask.” She pulled the blanket tighter about her. “But Jesus. Stop smoking, will you? There’s really no point in the oxygen if you’re just gonna keep that up.”

He hadn’t realized he’d had done it. But there it was: smoldering and waiting, right between his fingers.

Jim was looking at them on the porch, leaning on the cane, giving a thumbs up.

Claire returned the gesture.

Bud flicked the half-smoked cigarette into the can.

***

It was cold, dark. And he couldn’t breathe.

He opened his eyes.

He was outside, snow covering the ground. Trees surrounded him. He still couldn’t breathe. He reached up to his mouth and felt it. Something was wrapped around his face. He grabbed, pulled it. Vines. Vines were wrapped around his mouth. He yanked them free, tugging and tugging until he could finally suck in air. Bud stood, gasping, and looked around.

He was near the edge of the forest. He could tell because there was little Jim’s snow-deer. Antlers and all. But something was wrong.

He started to run, right into the forest, his cane wobbling as weak as a twig. The loose gray sweater flapped about him in the cold wind.

“Jim?!”

Bud needed to find Jim.

“Jim?”

Wet and cold from the snow, he came to a clearing. Large boulders broke through the white surface.

A flash of red among the trees on the other side.

He stumbled his way around the rocks, through to the trees. Hurrying, he entered the labyrinth of woods again. Tired. So tired and clutching a tree, regaining his breath. He felt something behind him, a swirl of energy, vibrant, warm. He turned.

There she was Mary Brennan, clad in a vibrant red coat, unmoving.

Bud’s breath steamed in the cold air.

“Bud,” she said. “What are you thinking?”

He couldn’t speak. He gripped his cane tight, tighter, until it jumped like a fish from between his fingers and he was on his knees.

Mary tilted her head as if confused. Then she rapidly thinned. The muscle sucked from her bones, skin stretched tight against them. A sunken face. Deep, empty eye sockets stared back at him.

Bud awoke in his bed. The hiss of the oxygen tank as terrible as silence. He curled up in his blankets and didn’t go back to sleep.

***

He was already out on the porch, painting by the time little Jim woke up.

The painting was coming along. The trees were like silhouettes, the moon just visible beyond them.

His grandson sat down next to him and grabbed a brush. He started to paint.

After a while, they headed inside for breakfast. The day was spent watching old films. Westerns, mostly. Jim’s favorite. A lone hero craving solitude above all else. One man alone with his thoughts for most of his life.

After dinner, Bud stepped outside. He lit a cigarette. It began to snow again. Lightly. There they were again, those lost feathers. He leaned against the window, overlooking the yard. And Jim’s snow-deer. It took him a moment to see the figure, but he did. A hint of red against the white. He breathed in sharply.

“What is it?” Jim had walked out from the house.

Bud pointed his knuckles, the cigarette jutting out from between them like a burning finger, to the tree line.

“A woman. She’s standing right past those trees. There. See her?”

Jim scanned the yard. “I don’t see anyone.”

“No. No, I suppose you wouldn’t.” He said with a grin, tossing the cigarette into the can by his feet.

The coughing started again. He walked into the house and took a drink of water from the tap. He sipped it, trying to calm the fire down in his throat.

He went back out to the porch when he was able to breathe. Just in time to see a little boy limp his way into the forest and disappear behind the dense curtain of trees.

“Jim!”

Bud almost slipped, clutching the cane like it was a ledge he was leaning over. He made it outside, shuffling through the snow towards the tree line. It wasn’t safe in there. He didn’t know what to think about Mary, but if Jim fell, he wouldn’t be able to make it back. It was too cold. Too cold out here for him. He would freeze. Bud was coughing.

He moved as fast as he could snaking his way through the trees.

“Jim!”

He kept going. No sign of the boy. Kept going. Coughing. Coughing.

He reached a clearing. The one he’d seen before. Dread rose up like a tidal wave, threatening to drown him. No. No. Not now. He kept moving. He was hacking up blood now. And there she was. In her red coat, standing amongst the trees. Mary.

“Bud.”

Shaking, he met her gaze.

Bud, rasping. “I can’t do this.”

“You have to let him go.”

“Where is he?” He coughed again, then shouting, “Jim?!”

“He’ll have a mother.” she said.

More blood.

“I know.”

He was so frail. So frail now. As broken as the twigs around him. His cane wobbled. And he sank to the ground.

“Grandpa?”

The snow still fell, melting as it touched Bud’s face. Coughing. Coughing. It threatened to choke him. Hot blood sprayed the white snow. He closed his eyes.

When he lifted his head, Jim was there. He was okay. Bud tried to wipe the blood from his beard but it had crusted.

“Do you see her, Jim?”

The boy, red-eyed with tears, said, “No. We need help.”

“It’s all right.” Bud reached for his cane and pushed himself up. With Jim’s help they went back to the house.

Jim helped Bud over to the rickety chair by the heater. He didn’t know what to do. Bud placed his hand on the boy, trying to comfort him.

“Do me a favor, pal. Go give Claire a call, hmm? Her number’s on the fridge. Just tell her to come over, ok? It’ll be all right. Go on.”

Jim limped inside.

He got to the phone, straining to see the number on the fridge, and dialed.

“Hello?”

“He says you need to get here, he’s bleeding, I—”

“Jim? Jim, what happened?” the voice on the line said.

“He was coughing, and then he started bleeding…he wants you here, I don’t know what…”

“James, listen to me, you stay with him, ok? I’ll be over there in five minutes, honey. You stay with him.”

“Ok.”

He hung up the phone and grabbed his cane, going back outside.

He stopped when he reached the porch.

Bud was slumped in front of his canvas, red-stained chin resting on his chest. His fingers covered in black. A paintbrush resting limply in his hand.

Red lights flashed against the windows. Some men came in. They ran to Bud. But Claire went straight to little Jim and held him. She told him it was going to be okay. She looked at the painting in front of Bud. It was a landscape, full of snow and trees. Three figures stood just outside the tree-line, two of them silhouettes. One red, the others black. And a deer made from snow. Antlers. Even antlers.

Leave a Reply