ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

From Berkeley, CA, Sonya Egoian is a junior double-majoring in Political Science and Narrative with a minor in French.

“Even in the most innocent of minds, there are still secrets best left unrevealed.”

– Stephen King, The Outer Limits

Released in June of 2012, director Ridley Scott’s fifth installment of the Alien saga, Prometheus, was marketed as nothing short of a highly-anticipated blockbuster.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-EZC5zn2Fk

A prequel to the popular Alien franchise, the film follows the crew of the spacecraft Prometheus as they land on a distant plant only to discover a deadly life form that turns their journey into a nightmare. Though packed with thrilling action, computer-generated imagery, and the always sultry Charlize Theron, Prometheus was widely considered a box office disappointment in the U.S., only raking in $125 domestically against its $130 million production budget. Despite its success overseas, the film swiftly faded from the lips of critics and the American public alike as Hollywood hype turned toward Marvel’s The Avengers and Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises.

Its absence from public discussion was unfortunate, however, as the film’s summer release preceded NASA’s August launch of the rover Curiosity with the goal of assessing whether Mars was ever an environment hospitable for microbial life. Although Prometheus does not directly address the possibility of life on Mars, the film certainly grapples with extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) and, more specifically, the potential for its interaction with mankind. Numerous scholarly and popular media sources have already addressed the societal implications and ethical dilemmas arising from the pursuit of extraterrestrial life on Mars, and there is no doubt that the questions and concerns Prometheus raises would foster lively and thought-provoking debate with its relevance to current events.

While the bulk of the Alien franchise paints a violent and threatening picture of alien life forms, Prometheus makes a marked departure by delving into deeper and darker questions about the origins of mankind. As archaeologists Elizabeth Shaw, Charlie Holloway, and the rest of the crew of the scientific vessel Prometheus encounter mounting terror while exploring a distant moon, their awe-struck curiosity about mankind’s creators gives way to the realization of the dangers of wanting to know too much. As one-by-one, the crew members meet their demise at the hands of the alien “Engineers,” the film’s conclusion seems to discourage the notion of questioning too pressingly about our origins.

Offering a harrowing theory about the creation of mankind, Prometheus suggests that, perhaps, we are not destined to know how and why we came to populate Earth. The constant tension between the human crew and their alien counterparts, as well as between the on-board android David and his human creator, suggests that a less scientific, more speculative approach to explaining mankind’s origins would be both safer and more satisfying.

“You convinced me that, if these things made us, then surely they could save us.”

The pointed deaths of the crew members—namely aging billionaire Peter Weyland—coupled with Elizabeth Shaw’s firm appeal to go back to Earth and to leave the distant planet forever alone, suggest that the initial probative goal of Prometheus was misplaced and recklessly incautious. Foremost, director Ridley Scott’s decision to eradicate the whole crew—save Shaw, who emerges with an altered perspective on man’s relationship with the Engineers—illustrates his belief that, by unveiling more information and pushing the borders of knowledge, modern science and research become increasingly entrenched in the unknown.

While the crew’s genuine curiosity perhaps only indirectly leads to their deaths, the death of Peter Weyland, CEO of the Weyland Corporation and sponsor of Prometheus, strongly argues against an overly enthusiastic venture into the unknown. Sickly and aging, Weyland launches Prometheus as an explorative vessel with the ulterior motive of meeting the creators of mankind in the hopes of prolonging his life. He firmly believes that, through communication and interaction, the Engineers can be persuaded to prevent his death from old age. In his first encounter with Elizabeth Shaw aboard Prometheus, he confesses to her how her work stimulated his development of the Prometheus exploration: “You convinced me that, if these things made us, then surely they could save us.”

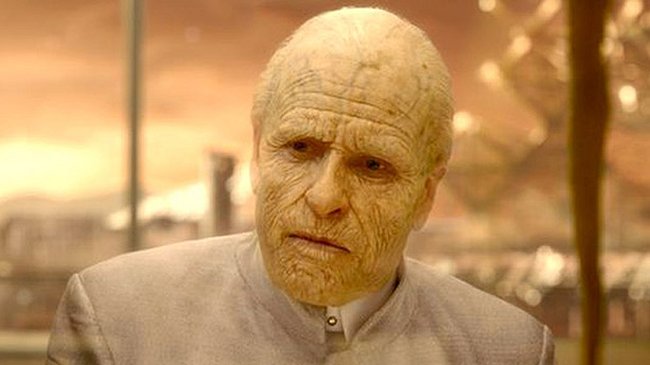

Perhaps the most driven of the crew members given his intentions, Weyland’s ultimate encounter with the Engineers is anticlimactic and disappointing. Frail and incapable of communication with the Engineers, Weyland is flung aside and left to die. In the last moments before his death, the audience sees Weyland’s weakness and desperation as he slowly becomes aware of the hostility and intimidation of the Engineers—despite the research and aspirations prior to Prometheus’s mission, they were entirely unprepared for the beings they intended to find.

Although Prometheus popularizes and fantasizes this possibility of sheer ill-preparedness and unknowing in the event of an ETI encounter, it is an oft-explored scenario in academic circles, perhaps most prominently in Britain’s acclaimed scientific journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

In their introduction to a recent issue of Philosophical Transactions devoted entirely to the potential societal impact of discovering ETs, English space science professor John Zarnecki and Royal Society researcher Martin Dominik suggest that relying on our earthly understanding of biology and life when searching for ETs may be too short-sighted of an approach: “Advanced extraterrestrial life might be unconceivable to us in its complexity, just as human life is to amoebae.” Here, Dominik and Zarnecki posit the frightening possibility that even meticulous planning, strategy, and research leading up to the discovery of alien life forms may prove ineffective if the ETs surpass our capacities of comprehension and knowledge.

“We were all so wrong.”

This sentiment is eerily echoed in the aforementioned exchange between Weyland and Shaw as she attempts to dissuade him from meeting the lone surviving Engineer: “You don’t understand. You don’t know. This place isn’t what we thought it was—they aren’t what we thought they were… we were all so wrong.” As Weyland and the larger Prometheus crew function as symbols of both the cutting edge of science and corporate America, their definitive deaths in the wake of their mission illustrates the futility of knowledge and wealth in the face of something greater than mankind itself. More importantly, the film suggests that it is precisely because of knowledge and the greediness of materiality (represented in Weyland’s desire to prolong his life) that the crew becomes engulfed in their fateful predicament.

Humankind’s inconceivability and misunderstanding of extraterrestrial intelligence, which Elizabeth Shaw desperately expresses, is a significant source of conflict not only for the crew of Prometheus, but also for scholars and researchers debating the ethical implications of the search for intelligent life forms. Acclaimed author and American astrobiologist David Grinspoon chimes in to support Shaw’s words. In his elegantly-crafted and thought-provoking nonfiction novel Lonely Planets: The Natural Philosophy of Alien Life, Grinspoon investigates the relationship between humanity’s evolution of philosophy and culture and the modern-day search for intelligence on other planets. Encouraging a highly self-reflexive approach, Grinspoon writes:

Even if we found a decent definition that worked for all life on Earth, we wouldn’t know if it applied anywhere else. We have no outside perspective. The fact that we have only one form of life to study was not obvious when biology was a new science. After all, trillions of diverse creatures are on Earth to compare and contrast. Now we know that they—and we—are all branches of one sprawling evolutionary shrub with a single root. Our limited and parochial knowledge of the nature of life makes any confident statement about life elsewhere an affront to the scientific method. Nevertheless, we can’t help it, because we so desperately want to know about life in the universe.

With this passage, Grinspoon articles and expands on Shaw’s earlier remark to Weyland. He presents his readers with a dichotomized view of life in the universe: life can seem unique and rare when considering the vast and diverse species on Earth, or it can be found on any planet with a supportive environment because in our sample size of one, we have found life. His language becomes more critical as he asserts that any conclusions researchers make are an “affront to the scientific method,” which can be distilled to a process of observation, hypothesis, experimentation, and revision.

Grinspoon acknowledges the risks and dangers of approaching outer space exploration armed with limited knowledge about and no experience with extraterrestrial life (let alone intelligence). However, Grinspoon has a more neutralized tone toward our penchant to explore deeper and farther; resigned to mankind’s curious nature, Grinspoon realizes that, without continued exploration of planets, it will be impossible to supplement our knowledge and begin the scientific process.

Ridley Scott, on the other hand, argues against it, suggesting that humankind is not yet ready to compromise their position in the universe. While the societal implications of an ETI encounter have been hotly discussed in diverse forums of academia and popular culture, the self-reflexive and philosophical aspect of the debate is less explored. Among the films in the Alien franchise, Prometheus is the first film to deeply explore the conflict of mankind’s identity in the face of an intelligent, alien being, with the friction between our curiosity and our comfort becoming more and more evident as the film progresses.

“The fact that we have only one form of life to study was not obvious when biology was a new science. After all, trillions of diverse creatures are on Earth to compare and contrast. Now we know that they—and we—are all branches of one sprawling evolutionary shrub with a single root.”

Berkeley theologian Ted Peters, however, has plunged into this issue with several papers about astro-ethics and extraterrestrial intelligence, offering insight into the conflicts at the heart of Prometheus. In a 2008 paper, Peters covers not only the practical effects of the discovery of alien life on society, but also its influence on human dignity and identity. He asks the provocative questions, “Will extraterrestrial life forms be similar to us or different? Like us or alien?” Moreover, Peters hypothesizes that mankind may be eager to categorize ETs as “1) inferior, 2) peer, 3) superior.”

Here, Peters highlights mankind’s tendency to both differentiate others from themselves as well as rank them based on their perceived value—Weyland is certainly guilty of the latter in his frantic attempt to persuade the Engineers to “save” him. Venerating the Engineers as superior and more advanced than mankind, Weyland overlooks their intentions and considerations in the process to extract useful information and technology from them. Peters goes on further to write that a potential future encounter with extraterrestrial intelligence will serve to “remind ourselves of just who we are.” Evidently, our identity and self-understanding will be irrevocably altered upon meeting an alien “other” (or, in the case of Prometheus, an alien creator), and neither Peters nor Scott can decisively say that man is prepared for such a change.

Furthermore, the marked emphasis Scott places on the strained relationships between the figures in the film who function as “parents” and their “children” illustrates his advocacy of distance and separation between creators and their creations. Most notably, he explores the violence and disregard the Engineers express toward their human descendants, but also the disgust Charlie Holloway exhibits toward David, an android designed by Weyland himself, reveals his disdain for a child trying to maintain a close relationship with a parent he does not truly understand. David’s inability to connect with Weyland mirrors that of the humans and the Engineers. Even in their limited dialogue, Holloway clearly scorns David’s inhuman relationship with his maker:

CHARLIE: You think we wasted our time coming here, don’t you? What we hoped to achieve was to meet our makers, to get answers—why they even made us in the first place.

DAVID: Why do you think your people made me?

CHARLIE: We made you because we could.

DAVID: Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?

CHARLIE: I guess it’s a good thing you can’t be disappointed, huh?

DAVID: May I ask you a question? How far would you go to get your answers? What would you be willing to do?

CHARLIE: Anything and everything.

Here, Holloway’s insensitive comment about the superfluity of David’s creation hinges upon David’s inability to feel emotions like disappointment and anger. With his technical prowess and advanced form, David is a paragon of modern scientific achievement, yet Holloway’s contempt toward him stems from this very inhumanity. Holloway’s remarks plainly show how he values the intangible quality of “being,” which makes the fact that the crew of Prometheus comes to realize that the Engineers express the same inhumanity and unfeeling toward them that much more disturbing.

Zarnecki and Dominik again offer insightful commentary on the discussion of human nature and the hunt for extra-terrestrial life, arguing that “the detection and further study of extra-terrestrial life will fundamentally challenge our view of nature, including ourselves.” The research duo articulates that the discovery of the alien “other” will undoubtedly shift the way we view life on Earth and prompt us to redefine our understanding of humanity. When time and time again history and philosophy have evidenced a heavily selfish and ego-centric view of mankind, we cannot help but wonder if mankind will ever be fully prepared to “make room” for a new life form.

“How far would you go to get your answers? What would you be willing to do?” “Anything and everything.”

Although Zarnecki and Dominik’s article was published in a 2011 issue of Philosophical Transactions, the questions the researchers raise seem to be nearly in response to those that emerge in Prometheus. In pursuit of discovering mankind’s maker, Holloway indeed risks “anything and everything”—including his own life—which only seems reckless and futile after considering how few “answers” he actually stumbles upon. His limitless and driven efforts seem ill thought-out and over-eager. With the brief yet poignant exchange between Holloway and David, Scott underscores the foolhardiness of plunging into exploration and contact with our own unknown origins. He suggests that humankind exhibits little care or thought toward our own technological creations, and that our creators may just as easily adopt this attitude toward mankind.

Surely picturing something similar to the warfare and violence that ensues between the Engineers and the crew, Zarnecki and Dominik warn that “such an endeavor may rather turn out to be a threat to our own existence.” Certainly, classic novels like H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds and more contemporary films like Independence Day have illustrated fantastical visions of total warfare between mankind and alien invaders, but the possibility of inter-planetary contamination poses a much subtler, though equally disastrous, consequence of advancing exploration of deep space.

An alien in the Hollywood sense may be easy to identify, but microbes and microscopic organisms that may contaminate spacecraft raise additional concerns to the surface, namely planetary protection and disease prevention. Always comprehensive in his cinematic endeavors, Scott does not gloss over this latter possibility. After their terse exchange, David splits a substance he extracted from the planet’s soil into a glass of water from which Holloway drinks, and within twenty-four hours he contracts a contagious and fatal disease.Even in the absence of the Engineers, he is killed by a foreign body nonetheless, advancing the sense of unknowing and entrapment that saturates Prometheus.

In unveiling the dark curtain shrouding outer space exploration, Scott reveals mankind’s problematic desire to fervently seek what may lie beyond our understanding. While Grinspoon and others may recommend that mankind tread lightly when exploring deep space, Scott seems to discourage treading at all. The overt annihilation of the crew, coupled with the hostility of the Engineers, clearly underscores the dark underbelly of pushing the borders of knowledge, science, and exploration; the Engineers play a near “bogeyman” role, scaring the audience into relying on the comfort and safety of the known world.

With the diversity of both life and thought that already exists on our planet, Scott suggests that there is little need to search for the undefinable “other.” An artist himself, he mimetically employs the film to show the breadth of mankind’s capacity; Prometheus expresses an inherent sense of pride in mankind. At its core, Scott uses Prometheus as a vehicle to suggest that, uniquely gifted with imagination and creativity, mankind should instead look within to find the answers to the question of our origins.

Sources

Anders, Charlie Jane. “Biggest Box Office Hits and Misses of Summer 2012.” io9. 13 Aug. 2012. Web.

Dominik, Martin and John Zarnecki. “The Detection of Extra-Terrestrial Life and the Consequences for Science

and Society.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 269.1936 (2011): 499-507. Print.

Grinspoon, David Henry. Lonely Planets: The Natural Philosophy of Alien Life. New York: ECCO, 2004. Print.

Peters, Ted. “Anticipating Detection of Life in Space: AstroEthical Scenarios.” Journal of Lutheran Ethics 8.10 (2008). Print.

Prometheus. Dir. Ridley Scott. 20th Century Fox, 2012. Film.

Randolph, Richard, Margaret S. Race, and Christopher McKay. “Reconsidering the Theological and Ethical Implications of Extraterrestrial Life.” The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences 17.3 (1997): 1-8. Print.

“The Revelations of Becka Paulson.” The Outer Limits. Showtime. CFCF, Canada. 6 Jun. 1997. Television.

Leave a Reply