Earlier this month, the French publication, Charlie Hebdo, was attacked by gunmen offended by the magazine’s portrayal of the Prophet. The attack and the following manhunt and hostage crisis caused by these gunmen has thrown France in a state of fear. The assailants had been born in France to Algerian parents, similar to one of their victims who was a police officer.

France has a different attitude towards religious freedom than Americans—as a result of rhetoric that originated during the French Revolution, France is a more secular country. Charlie Hebdo, as a publication, not only accepted the divide between religion and state, but relished mocking religion. Stephane Charbonnier, the former editor of Charlie Hebdo, said that, “We have to carry on until Islam is as banal as Catholicism.”

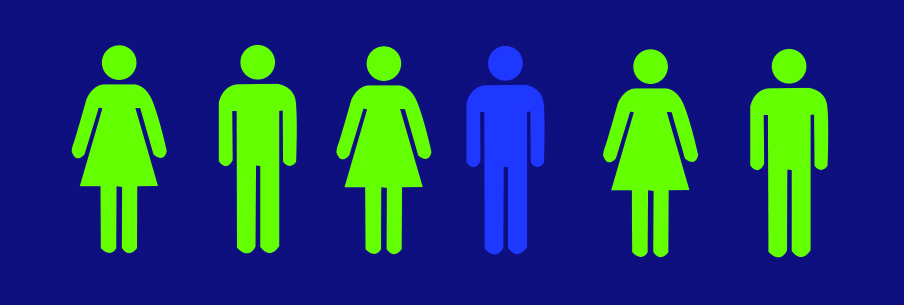

But Catholicism was never a religion from the outside—it was entrenched in France long before the idea of laicite came along. Islam, while having deep roots in France, suffers from the notion that it is a religion of outsiders. Some of France’s own Muslims, angered by a sense of economic and social exclusion, are accepting this dialogue of them being outsiders. On Wednesday, a boy and his father were questioned by the police; the boy had refused to obey the minute of silence honoring the victims, and then defended the terrorists’ actions[1]. Others in France have been sentenced to prison for speaking in favor of the terrorists.

While most of us cannot ever imagine supporting what these people are saying, locking them up in prison seems to be an action charged with fear. “Maybe if we lock these French citizens up, they can’t turn on us like the terrorists in Charlie Hebdo did.”

Locking them up is almost an act of war; a great number of people have been alienated and no longer feel that France’s values fit their own values. Moreover, due to economic constraints, these alienated individuals are often living together. In some schools, three-quarters of students refused to honor the moment of silence, saying that the attacks were justified.

France has to confront how it has, wittingly and unwittingly, excluded such a large number of people. There are those who have been incorporated into French culture, such as Ahmed Merabet, who died in the line of duty, and those who see France as their enemy. The rhetoric by far-right parties is definitely not going to encourage them to feel French.

France has to feel its way into the future. Imprisoning those who speak for the terrorists is an instinct driven by fear. France has proposed directing resources towards education, specifically on secularism and republican values. But France has to critically examine what is happening with its recent immigrants now—if they’re to become French citizens, they’ll have to be no longer outsiders in the banlieue.

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/30/world/europe/french-police-questions-schoolboy-said-to-defend-charlie-hebdo-attack.html?_r=1

Leave a Reply