In 1876, an American man stowed on board a Spanish ship under the guise of a common seaman. His name was William Macy “Boss” Tweed, and he was reigned as the “boss” of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party political machine which held much sway over 19th century New York politics. During his regime, he tripled the city’s bond debt to almost $90 million dollars, paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes, and stole from $25 million to $40 million – to about $200 million in later estimates – of New York tax money through political corruption (Ackermann 2005). A few years prior, he had been one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in New York, and it seemed like no one could stop him (Burrows & Wallace, 1999).

While on the Spanish ship, he was on the run. His Tweed Ring had been destroyed by exposé pieces from The New York Times, and more importantly, by the political cartoons of Thomas Nast, which through months of attack shed light on Tweed’s corruption (Boime 1972; Burrows & Wallace, 1999). Tweed reportedly once said, “Let’s stop them damned pictures. I don’t care so much what the papers write about me–my constituents can’t read–but damn it, they can see pictures!” (Compton 2008; Jackson 2000) Tweed would soon be caught coming into Spanish borders, recognized from one of Nast’s cartoons (Nilsen 2008).

Throughout history, political cartoonists have managed to affect politics with their medium. Most historians agree that cartoonists like Nast had at least some influence over the events that followed the publication of their works (Compton 2008). As well as helping to take down the corrupted Tweed Ring, Thomas Nast “profoundly affected the outcome of every presidential election during the period 1864 to 1884” with “the strength of his visual imagination” (Boine 1972 43). Cartoonist Herbert Block coined the term “McCarthyism” and helped turn public opinion against the Nixon administration with his visual editorials, winning three Pulitzer Prizes throughout his lifetime by having a solid reputation as one of the countries’ foremost political commentators during the 20th century (Compton 2008, Graham 1993). Even in the 21st century political cartoons still have a great influence: initially in the Iraq war, the American government did not allow any pictures of killed soldiers’ flag-draped coffins, but relented after cartoonists brought them to the attention of the public by drawing them instead (Nilsen 2008).

These are a few historial examples of the effectiveness of political cartoons on framing public opinion. Despite making up only a small part of print media, cartoons are considered to play an integral role in the editorial portion of newspapers (Abraham 2009). Political cartoons have been described as “powerful forces in affecting attitudes and beliefs,” “one of the most powerful weapons in the journalistic armory,” and “a vital component of political discourse” (Compton 2008 40). Like journalists, most political cartoonists’ primary objective is to create and manipulate public opinion (Coup 1969; Abraham 2009). But, unlike news reports, cartoons do not have to claim objectivity; they are very much opinion pieces that interpret current events and information (Nilsen 2008). As Abraham notes, cartoon’s representations “constitute ways of knowing, articulating, and interpreting different facets of our environment, and thus ways of exerting knowledge and power in society” (2009).

Yet despite the historical evidence Nast’s and Block’s illustrious careers seem to provide and the easy logic behind the beliefs of supporters, there are those who doubt the effectiveness of political cartoons in framing social issues. Abraham notes that political cartoons are often dismissed based on the grounds of “political absurdity and ideological insignificance,” meaning that their brevity and use of humor make it difficult for some to see cartoons as influencing the serious world of politics and social issues ((2009, 120). “Sociologists normally dismiss their ideological import,” Greenberg observes, “on the grounds that cartoons simply offer newsreaders absurd accounts of putative problem conditions and are not likely to be taken seriously” (2002).

For this reason, although there have been a plethora of analytical and critical works written which scrutinize political cartoons, very little experimental research has been done to provide empirical evidence for the effectiveness of political framing through this unique medium (Abraham 2009, Compton 2008, Nilsen 2008). This experiment’s main purpose is to provide more empirical evidence of political cartoon’s effect on emotional response and effectiveness in framing social issues to supplement what history seems to show.

A major component of this experiment builds off one of the few political cartoon research experiments, which was done by Del Brinkman in 1968. In his experiment, he showed study groups editorials, cartoons, and cartoons matched with editorials. What he found was that, though editorials were more persuasive than cartoons alone, a cartoon paired with an accompanying editorial persuaded people more than either one alone, meaning that political cartoons have a positive effect in persuasion (Compton 2008). This experiment will closely emulate Del Brinkman’s in that the independent variables will be textual editorials, editorial cartoons, and the two paired together, in order to confirm if the results of Del Brinkman’s experiment would still hold true today with in regards to the contentious issue of gay rights.

In a broader sense, as the independent variables are essentially text versus visuals, this is also a study on the effectiveness of visual framing in general. The majority of scholars who believe in the effectiveness of political cartoons credit their persuasiveness to the compactness and brevity in showing information and opinion. Paradoxically simple and complex, editorial cartoons “condense and reduce complex issues into a single, memorable image often pregnant in deeply impeded meanings” (Abraham 121). The reason why cartoons and visuals are so effective is because they give people “a visual handle for what they already knew and felt” (Jackson 2000). The brevity of visuals appeals to the current fast-paced, information-loaded culture visual products have become salient (Abraham 2009, Nilsen 2008).

The second interest of this experiment deals with the emotional response that political cartoons elicit within their readers and its correlation to persuasiveness. Though there is a dearth of research on the role of emotion on political communication, as most research efforts study cognitive rather than affective response, there are those who have noted that “emotions can play a crucial role in how citizens process political information and arrive at political judgments” (Gross 2008 169). Gross’ experiment found that between thematically centered articles and episodically framed ones, the latter were more emotionally engaging and would be more persuasive than the former. In another example, Brewer found that participants in his experiment “might have rejected frames that made them angry and accepted frames that did not,” meaning that their emotional reaction to a certain frame depended on their positive or negative opinion of it (2001, 57). The study of emotional response is important to political cartoons because more often than not they elicit a response that is primarily affective. Cartoons, by manipulating and distorting simulations of our real world visual experiences, “elicit attention and emotion, and orient us to particular points of view” (Abraham 2009 152).

Based of the research done by Del Brinkman and Wheeler, as well as the critical research of many other intellectuals, this experiment searches to confirm political cartoon’s effectiveness as a visual medium. It also seeks to confirm this connection between framing through political cartoons and emotional response, and from this, supplement Gross’ study between emotional response and persuasiveness. Thus, the hypotheses of this experiment are:

(H1) On the basis of previous visual framing research and experiments, the sample with both a cartoon and article will be the most persuasive.

(H2) On the basis of previous research on emotional response, the sample that is most persuasive will also garner the strongest emotional responses.

Method

In order to explore the effect of visual framing on emotional response, as well as the correlation of this emotional response and persuasiveness, we conducted an experiment which focused on participant’s emotional reactions to an article on gay and lesbian personnel in the army, a trending debate since the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy had been repealed in December 2010. In the spring of 2011, the experiment was conducted online at YourMorals.org, a scientific research website whose main goal is to “understand the way our ‘moral minds’ work.” The participants of this experiment elected to choose a study entitled “Media Framing Study 1 – What are your reactions to these 3 news stories about Facebook privacy, gays in the military, and the Falun Gong?” Each one is a separate experiment, albeit all concerning media framing. This experiment concerns the second story, the story about “gays in the military.”

Participants

The sample was a total of 247 participants who answered the questions of the experiment, of which 41% participants identified as female, while the remaining 59% identified as male. The average age of participants was 35 years old, with the median age of the sample at 34 years old. Of the participants, 20% completed a graduate or professional degree, 19% completed college or university, and 30% were currently in college or in a graduate program. Most also had an interest in politics, with 41% professing that they were “somewhat interested” in politics, and 52% profession that they were “very interested” in politics.

The majority of participants have a liberal bias, with 57% participants self-identifying as liberal, 9.7% self-identifying as conservative, and 12% self-identifying as libertarian. This is only a general overview of the sample’s political makeup is given for simplicity’s sake; however, it should be noted that most participants cannot be strictly defined by the left-right political spectrum and have their own complex political ideologies. This complexity was revealed when participants were asked to give their political view on a few areas of politics, and when several of the participants elaborated even further on their political identities in the comments section provided on YourMorals’ registration. On that note, concerning political standing on social issues, most participants chose to identify themselves at the left end of the political spectrum, with 32% saying they were very liberal, 26% saying they were liberal, 9.3% saying they were slightly liberal, and a mere 7.7% saying they were any form of conservative at all.

Finally, in terms of religious values, 55% said they had “no religion” and 17% identified with some Christian denomination, though 56.3% stated they were raised in a Roman Catholic or Protestant household.

Procedure

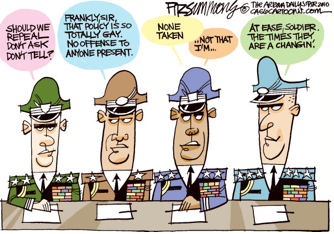

The study included a textual article on the subject of gay and lesbian personnel serving in the military from MSNBC.com titled: “Admirals, generals: Let gays serve openly – More than 100 call for repeal of military’s ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy” (Appendix A), as well as a political cartoon on the subject of gay and lesbian personnel in the military by David Fitzsimmons for the Arizona Daily Star (below). The textual article was chosen for its relatively positive (as opposed to normative) news reporting, and the cartoon was chosen for its relevance to the content of the article, as it depicted generals speaking negatively about the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy.

This study also hoped to find correlation between emotional response and persuasiveness and includes both negative and positive emotions. This means finding out if strong positive emotions make the participant perceive that the sample is persuasive and strong negative emotions make the participant perceive the opposite. The highly contentious issue of gay and lesbian rights, the topic this experiment is used on, is used because of the strong emotions it usually elicits in people to help meet the experiment’s objective.

Participants are randomly assigned to one of three conditions:

- Condition 1, which contained only Fitzsimmons’ political cartoon, and is meant to represent visual framing.

- Condition 2, which contained only the MSNBC textual article, and is meant to signify simply textual framing.

- Condition 3, which contained both the political cartoon and the textual article, and is meant to signify textual framing supplemented by visual framing.

After reading their assigned condition, the participants were given ten statements and were asked, on a scale of one to seven, to say whether they agree or disagree with each question. Four of these questions (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) asked the participants about their opinions concerning gay and lesbian rights as well as the government’s involvement in social activism (Appendix C). These questions are used partly to reveal participants’ biases, but their main purpose is to make the study’s true purpose less transparent. The exact wordings of these questions were created for the purpose of this study, but data-collecting websites such as Gallup.com have asked several questions concerning the public’s opinion on gay rights on which they are loosely based.

The remaining six of the ten questions were meant to gauge the participant’s emotional reaction to the stimulus, as well what he or she perceives to be its persuasiveness (Appendix D). Of the six questions, two questions connected the stimulus to positive emotions (Q5 and Q9) to see if participants would react with positive emotion to the stimulus, and with what intensity. This was in order to see if visual framing indeed elicits strong emotional response, and if it is positive. Another two questions connected the stimulus to negative emotions (Q6 and Q8) in order to see whether the stimulus would produce strong or weak emotional reactions in the negative spectrum. The remaining two questions (Q7 and Q10) connected the stimulus to persuasiveness, to see whether the persuasiveness ratings participants gave the stimulus would correlate with their ratings of how positive or negative they found the condition. As with the first four questions, participants were asked show on a scale of one to seven how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

Finally, the order in which the ten questions were asked were randomized in order to further obscure the objective of the study and prevent from inadvertently priming the participants.

Results

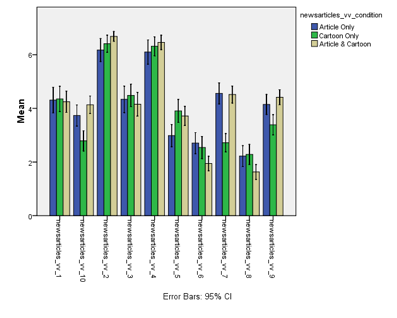

The chart below graphs the average score for each question given to the participants in each condition. It is apparent from the results that the first hypothesis, which stated that the sample with both the cartoon and the article would be the most persuasive, has turned out to be correct. While Q7 did not garner any significant outcome, Condition 3 was found to have the highest rating for Q10 by a significant amount, meaning that participants found the article and cartoon combination to be the most persuasive condition. Similarly, results for Q2 showed that the participants who received Condition 3 agreed more with the statement “Gays and lesbians should be allowed to serve openly in the military” than participants in the other two conditions. This is perhaps the most significant finding because it shows that the article and cartoon combination is more effective in persuading participants in the direction of pro-gay rights than the cartoon or article alone.

Graph – Participant Responses to Questions

In terms of the first hypothesis, the results of this experiment support Del Brinkman’s research in 1968, wherein he found that the combination of article and cartoon was found to be more persuasive than a textual article or cartoon alone. It’s also interesting to note that the results of this experiment mirrors Del Brinkman’s even further. In this experiment, Condition 1 was rated significantly less persuasive – both in Q7 and Q10 – than Condition 2 or Condition 3, meaning that participants found the cartoon less persuasive than both the article and article/cartoon combination, just as participants did in 1968. Thus this experiment further supports the idea that while a political cartoon by itself may not be as persuasive in portraying an opinion as an actual article, it can be a very effective supplement as a visual aide in informing the reader.

The second hypothesis proved to be partly true when Condition 3 turned out to be the most effective (Q9), least offensive (Q8), and least disrespectful (Q6) of the three conditions. However, the condition that received the highest rating for being funny (Q5) was Condition 1, the cartoon alone, which also was the least persuasive (Q9) and least effective (Q10). In short, the article and cartoon combination was the condition least connected to negative emotions and the most persuasive, while the cartoon alone was the condition which participants attached the most positive emotion to, but was the least persuasive. From this, it can be assumed that instead of persuasiveness being correlated to strong emotional reactions, it is instead correlated to a lack of a negative emotional reaction.

The reason for this outcome most probably goes back to observations made by Abraham and Greenberg about the general dismissal political cartoons face from scholars on the grounds of “political absurdity and ideological insignificance.” Because the punch from their emotional impact often comes from ridicule and absurdity, political cartoons are often treated as merely entertainment, nothing more. The reader compartmentalizes the emotional reaction to the fictional world of the absurd, and thus disregards when creating an opinion on a topic which the reader classifies as reality. However, this knowledge does not invalidate a political cartoon’s effectiveness as a visual aide that supplements the information a reader receives from an accompanying article. To reiterate Jackson, cartoons give people “a visual handle for what they already knew and felt,” acting as a summary of the article worth a thousand words (2000). Like study guides, political cartoons cannot be the main transmitter of information. They are often too brief, too opinionated, and too ambiguous, but they serve well to summarize and make memorable information already known, still making them effective framers of political opinion.

Appendixes

Appendix A: Textual Article

Admirals, generals: Let gays serve openly

More than 100 call for repeal of military’s ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy

ANNAPOLIS, Md. — More than 100 retired generals and admirals called Monday for repeal of the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy on gays so they can serve openly, according to a statement obtained by The Associated Press(…)

“As is the case with Great Britain, Israel, and other nations that allow gays and lesbians to serve openly, our service members are professionals who are able to work together effectively despite differences in race, gender, religion, and sexuality,” the officers wrote(…) (ARTICLE ONLY) “The times are changing.”(…)

The officers’ statement points to data showing there are about 1 million gay and lesbian veterans in the United States, and about 65,000 gays and lesbians currently serving in the military.

(ARTICLE ONLY) “Frankly,” one officer joked during conversation, “that policy [DADT] is so totally gay. No offense to anyone present.”(…)

The military discharged about 12,340 people between 1994 and 2007 for violating the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, according to the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network, a military watchdog group. The number peaked in 2001 at 1,273, but began dropping off sharply after the Sept. 11 attacks.

Last year, 627 military personnel were discharged under the policy.

Source: MSNBC.com

Appendix B: Political Cartoon

Source: David Fitzsimmons

Appendix C: Questions 1-4

Q1. The government should play a prominent role in social activism.

a. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q2. Gays and lesbians should be allowed to serve openly in the military.

b. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q3. I closely follow the news and opinions concerning Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.

c. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q4. Homosexuality should be considered an acceptable lifestyle.

d. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Note: Answers will be on a seven point scale.

(These questions are to make the study’s purpose a little less transparent, and also perhaps to see any strong biases.)

Appendix D: Questions 6-10

This article/cartoon was:

Q5. Funny

a. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q6. Disrespectful

b. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q7. Informational

c. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q8. Offensive

d. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q9. Effective

e. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q10. Persuasive

f. Strongly Disagree . . . . . . . . . . . Strongly Agree

Q5 and Q9 – Gauge Strong positive emotional response

Q6 and Q8 – Gauge Strong negative emotional response

Q7 and Q10 – Gauge Persuasiveness

References

Abraham, Linus. “The Effectiveness of Cartoons as a Uniquely Visual Medium for Orienting Social

Issues.” Journalism and Communication Monographs 11.2 (2009): 117-165. Print.

Ackerman, Kenneth D. Boss Tweed. New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 2005. Print.

Best, J. Images of Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems. New York: Aldine de Cruyeter, 1995.

Boime, Albert. “Nast and French Art.” American Art Journal 4.1 (1972): 43-65. Online Text.

Brewer, Paul R. “Value Words and Lizard Brains: Do Citizens Deliberate About Appeals to Their Core

Values?” Political Psychology 22.1 (2001): 45-64. Online Text.

Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: a history of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford

University Press, Inc., 1999. Print.

Compton, Josh. “More Than Laughing?: Survey of Political Humor Effects Research.” Laughing Matters:

Humor and American Politics in the Media Age. Jody C Baumgartner and Jonathan S. Morris. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2008. 39-63. Print.

Coupe, W. A. “Observations on a theory of political caricature.” Comparative Studies in Society and

History 11 (1969): 79-95.

Del Brinkman. “Do Editorial Cartoons and Editorials Change Opinions?” Journalism Quarterly 45 (1968):

724-726.

Graham, Katharine. “Introduction.” Herblock: A Cartoonist’s Life. Reed Business Information, Inc., 1993.

Print.

Greenberg, J. “Opinion discourse and Canadian newspapers: The case of the Chinese ‘boat people.”

Canadian Journal of Communication 25.4 (2000): 517-38.

Gross, Kimberly. “Framing Persuasive Appeals: Episodic and Thematic Framing, Emotional Response, and

Policy Opinion.” Political Psychology 29.2 (2008): 169-192. Print.

Iyengar, Shanto. “Framing Responsibility for Political Issues.” Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science 546 (1996): 59-70. Online Text.

Jackson, Bruce. “Lazio’s Finger.” Artvoice 2 (2000). Web. 5 May 2011.

<http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~bjackson/lazio.html>

Nilsen, Alleen Pace and Don L.F. Nilsen. “Political Cartoons: Zeitgeists and the Creation and Recycling of Satirical Symbols. Laughing Matters: Humor and American Politics in the Media Age. Jody C Baumgartner and Jonathan S. Morris. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2008. 67-79. Print.

Spector, M. and Kitsuse, J. I. Constructing Social Problems. Menlo Park, CA (1977): Cummings

Thomas, Samuel J. “Teaching America’s GAPE (Or Any Other Period) With Political Cartoons: A

Systematic Approach to Primary Source Analysis.” The History Teacher 37.4 (2004): 425-446. Online Text.

Wheeler, Mary E. and Stephen K. Reed, “Response to Before and After Watergate

Caricatures.” Journalism Quarterly 52 (1975): 134-136.

Leave a Reply