ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Vellore Adithi graduated from USC this past May with degrees in anthropology and linguistics, as well as a minor in gender studies. She is currently pursuing her interests in education and social justice, working as a social studies teacher at Hyde Park Academy High School in Chicago.

Ever since Postmodern, Post-Structural writers and thinkers revolutionized our understandings of truth and reality by challenging the once-unassailable connection between language, expression, and self, questions of how identity is formulated—how it is conferred, claimed, and contested within existing cultural networks of shared meaning—have demanded our attention because of their complexity and their centrality to the social experience of difference. In Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, we can see how identity—marginal identity in particular—is not simply a fixed, context-less set of preexisting labels that we claim or that are conferred upon us, but is rather a dynamic and continual process of situating oneself among the abstract networks of language, meaning, and difference in a community. As such, identity formation is a matter of negotiating readings and misunderstandings of self, of coding and decoding the arbitrary and abstract language we inscribe on our very bodies, much as the chief narrator in Morrison’s novel, Claudia MacTeer, must navigate the notions of racialized beauty that are inscribed on black bodies as she develops her own identity of young, black womanhood in a racist society.

Claudia is uniquely positioned to help us investigate the process of identity formation because she finds herself at a critical juncture where her own sense of self is in conflict with the language and meanings of her society, a conflict which manifests in the interplay of reading and misreading, of the recognition and total misapprehension of that self. She describes the process of her personal development as a little black girl in a society enthralled by the icon of white, youthful beauty, Shirley Temple: “younger than both Frieda and Pecola, I had not yet arrived at the turning point in the development of my psyche which would allow me to love her” (19), she says, going on to situate her once-hatred for Shirley Temple along a well-developed timeline of a deeply visceral, violent confusion about her culture’s enchantment with white beauty and the fundamental misalignment of that enchantment with her own particular character and desires.

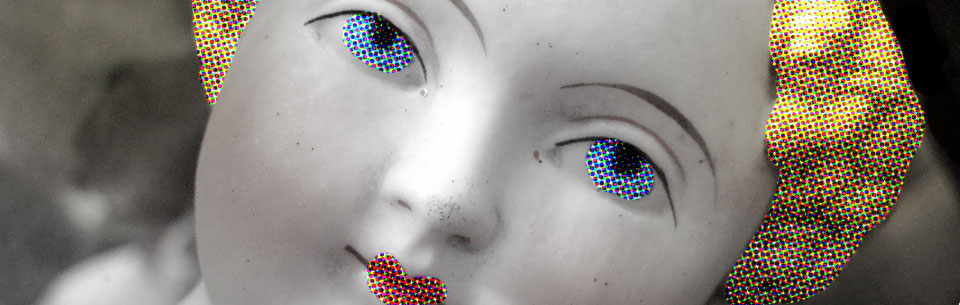

Claudia is forced to confront, physically and emotionally, this contradiction between the invisibility and inconsequence of her black selfhood and the racially-coded, popular cultural worship of whiteness when she is gifted with a white Baby Doll one Christmas. “I had only one desire,” she says, describing her unique experience with the cold, unyielding porcelain doll. “To dismember it. To see of what it was made, to discover the dearness, to find the beauty, the desirability that had escaped me, but apparently only me” (20). She struggles to understand how she and her desire have been so grossly misunderstood: she does not crave the pretense of motherhood; she does not take pleasure in cuddling with the cold, hard-limbed dolls that look nothing like her; she does not want to possess an object, but rather wishes to feel something, with every last one of her senses, on a Christmas day spent with her family. All the world, it seems to her, “adults, older girls, shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs…had agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured” (20), thus her only recourse is to dismember the dolls—and the little white girls they are modeled after—as she says, “to discover what eluded me: the secret of the magic they weaved on others” (22). So deeply unsatisfied with the exclusion manifest in the gift of the doll, but ill-equipped to verbalize her discontent, Claudia struggles to resolve her urgent, unanswered questions about self, color, worth, and beauty. Thwarted by a community that has failed both to represent her and to recognize her interests and desires, Claudia’s mounting desperation in her search for a meaningful and coherent self is palpable: “What made people look at them [little white girls] and say, ‘Awwwww,’ but not for me?” What special spirit did little white girls possess to merit “the eye slide of black women as they approached them on the street, and the possessive gentleness of their touch as they handled them”? (22-23).

These questions represent a critical interrogation of cultural knowledge, language, and shared meaning of the sort that Michel Foucault describes in his essay, “The Archaeology of Knowledge,” as a means of understanding how the contemporary production of knowledge occurs in a deeply historical lattice of discursive formations that society has already developed to unify and code the perceived units of our social experience. Foucault argues that the “systematic erasure of all given unities enables us…to restore to [a] statement the specificity of its occurrence,” such that we no longer take for granted the invisible ideological frameworks that constrain our lives, language, and the meta-discourse about our social experiences, and instead examine what knowledge exists in the ruptured spaces of discontinuity—spaces that emerge when we ask “what was being said in what was being said?” (quoted in Rivkin and Ryan 93). Claudia dismembers the doll in a brutal, physical erasure of the unities that order her world, ones which equate the hallmarks of whiteness—blue eyes, blond hair, pale skin—with beauty, and condemns blackness to associations with ugliness and dirt, in order to discover the underlying cultural framework in which that loathsome doll “was lovable” (21). In her own Foucauldian way, she questions the peculiar divisions and unities that conflate Shirley Temple and other little white girls with that-which-is-beautiful,treasured, and cherished, simultaneously devaluing, neglecting, and misreading the beauty and desires unique to young black girls like Claudia.

In asking these questions and in seeking to dismember-to-discover, Claudia engages in a process of becoming and identity formation—she learns to negotiate her own identity as a young black girl in light of her community’s pervasive belief in the goodness, cleanliness, beauty of whiteness, even as it denies her own emotional nourishment. She grudgingly learns her place after being continually misapprehended, adapting to the cultural codes by which the society regulates the discourse on beauty and race, very much in the model of the iconoclast-among-iconolaters philosopher Jean Baudrillard describes in his meditations on simulation, reality, and truth in his essay, “Simulacra and Simulations.” While “one can live with the idea of a distorted truth,” he argues, the iconoclast’s “metaphysical despair came from the idea that the images [of God] concealed nothing at all, and that in fact they were not images, such as the original model would have made them, but actually perfect simulacra forever radiant with their own fascination.” Confronted with the alarming “omnipotence of simulacra, this facility they have of erasing God from the consciousnesses of people” and the ultimate, devastating condition of the nothing-ness, the very un-truth of her God, the iconoclast must exorcise this “death of the divine referential…at all cost” (quoted in Rivkin and Ryan 367-8). So, even as Claudia dismembers the baby doll to discover the underlying truth, the enchanting magic the little-white-girl body weaves upon the world, it is dangerous and overwhelmingly ruinous for her to confront the essential nothingness that underwrites the privileging of whiteness in her society; the idea that her entire culture conspires in this deliberate, historicize-able misapprehension of the black body—and consequently, of her—is simply too much to bear.

Furthermore, Claudia must then reconcile the meanings and motivations of her violent discovery with the cultural codes reinforced by adults’ reaction to her hostility to the baby doll. “You-don’t-know-how-to-take-care-of-nothing. I-never-had-a-baby-doll-in-my-whole-life-and-used-to-cry-my-eyes-out-for-them. Now-you-got-one-a-beautiful-one-and-you-tear-it-up-what’s-the-matter-with-you?” (21), she quotes the adults’ near-tearful outrage that speaks to their old longing for these beloved figurines. In the face of this disharmony between self and society, and lacking in the discursive frame both to understand her destructive desire and to describe the nothingness that underlies the cultural valuation of the baby doll, Claudia learns to regard her disinterested violence as her society does: as a “repulsive,” shameful expression of self that can only be hidden in a “fraudulent love” for the dolls. She conforms, unwillingly, to the iconolaters of her society, perhaps out of an unconscious recognition that, as Baudrillard asserts, “it is dangerous to unmask images, since they dissimulate the fact that there is nothing behind them” (quoted in Rivkin and Ryan 368), that no truth or essential spirit of beauty in fact justifies the world’s captivation with whiteness.

And so, she recalibrates her identity, undergoing a “conversion from pristine sadism to fabricated hatred, to fraudulent love,” a reimagining of self that allows her to “worship [Shirley Temple]…to delight in cleanliness, knowing, even as I learned,” she says, “that the change was adjustment without improvement” (Morrison 23). Having learned the language of her culture, a language that unites beauty and whiteness and relegates blackness to a position of inferiority, having been misread as that-which-is-not-beautiful-and-must-therefore-desire-beauty-as-defined-by-culture, Claudia adjusts so that she can better participate in this culture, which nevertheless conspires to exclude her and her notion of selfhood. She learns to love Shirley Temple where she once felt hatred for her, she learns to take pleasure in the cleanliness she once considered the “dreadful and humiliating absence of dirt” (22), she learns to play the “game” of language and the hyperreal just as the iconolaters of her society do. She adjusts, but she doesn’t improve: she has already, at some level, confronted the nothing masked by the baby doll, the absence of any particular essence that makes little white girls so lovable and her so readily ignored; but, lacking the conceptual tools to satisfactorily identify and dismantle the invisible frameworks of racism and white privilege that obscure the cultural construction of equalities between whiteness, worth, and beauty, she must renegotiate the positioning of her identity, coerced to comply with a system that denies her black selfhood at every turn.

Claudia’s recognition at the end of this powerful passage in The Bluest Eye, that the change she makes to her self is “adjustment without improvement” is of paramount importance for us to understand how she forms identity as a marginal individual. She adopts a particular language and discursive coding to participate more fully in a culture that is nevertheless determined to misapprehend and exclude her, and so, she must reconfigure her identity to make space for her “fraudulent love,” which ultimately allows her to resolve the competitive disharmony of her subjective self-concept and society’s overwhelming act of (mis)reading of her black body as a soiled and inferior object. In this poignant scene of introspective interrogation of self and society, Morrison is able to illustrate how crucial reading as well as misreading is to the challenge of formulating a marginal identity in a hostile social space, raising pressing questions about the complicity and differential power relationships that infuse even the most mundane and minute experiences of difference in our shared social experience.

Sources:

Baudrillard, Jean. “Simulacra and Simulations.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. 2nd ed. Eds.

Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004. 90-96. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “The Archaeology of Knowledge.” Literary Theory: An Anthology. 2nd ed. Eds.

Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004. 365-377. Print.

Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970. Print.

Leave a Reply