By Cody Marion

In 1927, sound and image became forever linked with the production of The Jazz Singer, the very first feature film to synchronize dialogue with visuals. While some proclaimed it to be the death of filmmaking, others championed it, arguing that the medium was progressing and evolving into something much more engrossing than what had already been an undeniably successful art form. Indeed, sound and picture still exist as cinema today, as do their most fundamental attributes, though since the ‘20s countless alterations and advancements have been made – to the extent that contemporary audiences now find their own easily accessible home theater equipment far surpassing the once highly esteemed (now comparatively weak) major theater advancements previously wrought by the most skilled and insightful engineers of the early 1900s.

Knowing where we are today, modern sound buffs cannot help but possess a curiosity towards the ever-constant progress of sound as art – as a technologically complex tool with which a listener can immerse him- or herself unconditionally into a world of fantasy, escaping the stress and occasional tediousness of everyday life. Not only as a traditional cinematic device, but also in running on its own stamina as a psychoacoustic emotional trigger, sound is now reaching peaks – even limits – in its usage by mankind. In focusing on those here referred to as “technological artists,” creators with backgrounds built on more than merely the arts (e.g. Tomlinson Holman and Janet Cardiff), I will aim to demonstrate that certain people – particularly in the field of multi-channel, spatial differentiation – are yet facilitating filmic sound’s potential, still pushing its limits, in their desire to capture an audience’s imagination and subsequently integrate them more thoroughly (and enjoyably) into the world of make-believe.

How does multi-channel, spatial differentiation evolve from conception to reality?

Tomlinson Holman revolutionized the movie industry by contributing two vastly significant developments now involved in any professional cinematic experience: THX Theater Standardization and 5.1 Surround Sound. I was lucky enough to meet with Mr. Holman and, over the course of a few hours, touch briefly on the current focus of his attention and where he feels sound is now heading. However, in order to properly comprehend where Mr. Holman’s work lies, a basic knowledge of its history is first required.

Prior to the release of George Lucas’ Return of the Jedi in 1983, theaters were designed with little thought pertaining to the reproduction of a film’s soundtrack. THX brought a devotion of maintaining mixes sent out from studios by calibrating theaters to a certain paradigmatic design; thus, everyone could hear the same film. Shortly after came 5.1 Surround Sound, the methodical placement of speakers around a viewer, immersing him or her within the world of the story. Along with the inclusion of developments by Dolby and various other companies, audiences now find themselves living within the world of modern sound technology.

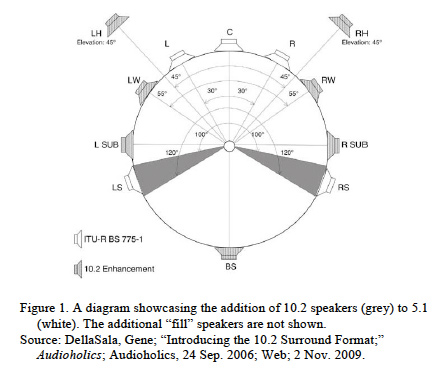

Today, obstacles regarding frequency limitation no longer exist; bit depth and dynamic range (the perception of the lowest sound a human can hear in relation to the highest) has vanished (Holman, Sound 65; 119). Theaters can now play recordings so well captured that it is nearly impossible to distinguish what is real and what is contrived. With so many tremendous accomplishments already reached, it must be asked, “To where is it leading?” This question was, in fact, posed to Mr. Holman, to which he quickly and assuredly responded by stating, “the one thing we need is spatial differentiation. This can be separated into two distinct parts: Imaging and envelopment. Imaging: the sense of placing sound in space; and envelopment: the sense of being immersed in that space” (Holman). He then mentioned that this could be accomplished through a simple, “logical logarithm,” one applicable to speaker position and quantity. Thus, from 5.1 one moves to 10.2: ten speakers and two subwoofers precisely calculated to engulf an audience, to erase all efforts in resistance of suspension of disbelief, and to thereby solidify an absolute

acceptance in an on-screen world.

The idea behind developing 10.2 is to essentially “fill in the holes left by 5.1,” to ensure that sound remains unbroken, a single invisible bubble encapsulating the hearer from one end of the room to another. In addition to the front speakers used by 5.1, 10.2 implements four more directed towards the front of the viewer (see fig. 1): a left center and a right center at roughly 45 degree angles from the screen, and two atop the original left center/right center speakers (much of our spatial discernment stems from these overhead locations). Positioned directly to the left and right of the viewer are the two subwoofers, placed on the floor; and directly behind the viewer is a new central back speaker, allowing sounds to pan more smoothly from left to right. The last addition, and the most interesting, is a pair of heightened speakers situated above the subwoofers (these actually raise the speaker count to 12). Each of these speakers is actually two, facing opposite directions perpendicular to the direction of the screen. These speakers pump out “fill tracks.”

A nice comparison to these “fill speakers” would be a glass of ice. Say the glass is full, though absolutely no air is to be allowed within it. In order to occupy the areas between the ice, the glass is filled with water. In the context of sound, 5.1 has issues panning (fluidly completing the movement of) an effect from one speaker location to another. In order to disguise the pan and prevent the audience from noticing a “jump” between speakers, fill sound is emitted throughout the entire room by the aforementioned “fill speakers,” in the process obliterating the notion that any single speaker exists whatsoever.

10.2 is most definitely achieving its objective of furthering the cinematic experience, and its standardization has already been set; indeed, it may be discovered in such media programs as QuickTime. A few theaters in the U.S. even have the system installed, though as of yet, no 10.2 feature films have been released. Nonetheless, upon experiencing Tom’s demo, which includes an expansive concert hall performance of Handel’s rousing “Hallelujah Chorus,” as well as a lightning fast, ubiquitous bouncing ping-pong ball swerving from one corner of the room to the next within a quarter of a second, it is undeniable that one quickly forgets he or she is merely sitting in a sparse, 30 X 20 foot dead-air room.

According to Tom, a less recognizable but still heavily important sound tech. company is Smyth Brothers, the developers of “coherent acoustics” for the DTS sound system and formidable experimenters of a new, nearly perfected calibration design. From what can be gathered on their latest work, it involves “probing a mic within a listener’s ear canal. The system emits chirps to loudspeakers [within the room where the sound will be heard], measuring transfer functions from loud speakers to ear canal, one’s pinnae” (Holman). Already, it feels beyond today’s capabilities, but Tom insists it exists, and works: “There’s a certain pattern of reflection, equalization and so forth. It calculates what you hear from the headphones to what you hear from your loudspeakers,” adapting them to the more rich experience provided by the headphones – calibration (and a resulting aural engagement) of the highest level.

Somewhere, the distinction between art and technology (one purely expressive, the other purely scientific) is becoming muddled as the two fields cross paths and begin to, more and more, merge as one unique craft. It is difficult to label someone like Tom; “Is he singly an artist or an engineer/inventor?” is not an appropriate question. At this stage of development and fine- tuning, in today’s high concept world, it almost appears as thought the mere act of creating requires a solid background in electronics, acoustics, etc. In fact, appreciation of sound is becoming so infused into the general public that those who today use or manipulate it for personal expression on even the mildest of terms could arguably be required (or even forced) to grasp a cardinal comprehension. And Tom, conversely approaching more from the engineering side of the spectrum, does not merely measure – he thinks, creatively. He laughed when he was referred to as an artist, explaining, “No, and I’m not a scientist or engineer either, though I pretend pretty well”; yet, when he described his thoughts on applying loudspeakers with Smyth Bros. individually calibrated headphones for the concept of a highly advanced Disneyland ride, it could not be helped but to infer that such progressive, intrinsically artistic ideas as this may be exactly where today’s forerunners of sound are headed. “Technological artist,” a solid amalgam of two distinctly separate fields, seems a fitting term to grant them, and another singularly fascinating example is the innovative and inspiring Janet Cardiff.

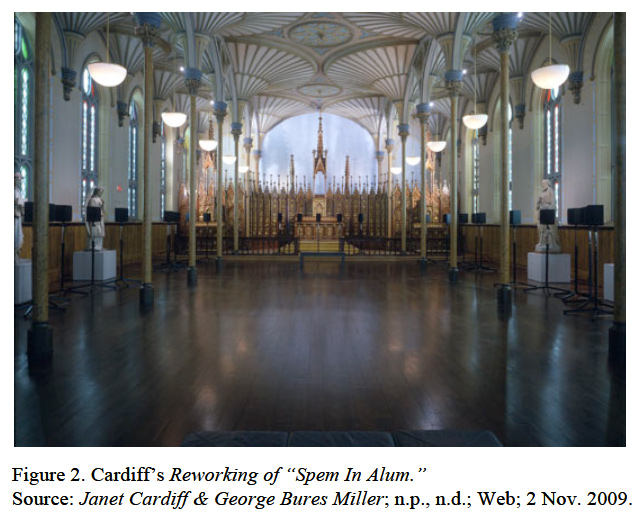

Wherever Janet Cardiff’s The Forty-Part Motet installation is presented, there is a unanimously positive reaction. Abounding reviews on its inherent majesty and tranquil power, its manifestation as “a landscape of sound [moving] like a wave of ever-shifting color, haunting and serene,” transmit the notion that it is something more than a contemporary work of art – it is bordering celestial (Ponnekanti 1). The full name of the project is Forty-Part Motet: A Reworking of “Spem In Alum” By Thomas Tallis. Motet is unique among artistic projects in its accomplishment of merging the complex fields of sound engineering and aesthetic presentation. It also tackles a progressive exploration of “spatialization, whereby perceptions of both aural and physical space are affected,” allowing for a seamless synthesis of mind and body response to an artificial event – what one hears and what one experiences (MacDonald 61).

As in contemporary cinema, Cardiff’s intent is to effectively fashion an acoustically

living environment via loudspeaker. By recording each individual chorus member onto his or her own track and then feeding that naked track out to its own individual speaker, Cardiff electronically replaces a standing robed soprano or tenor with a thin, black, rigid box: in effect, forty machines replace forty voices (see fig. 2).

Next, the speakers are placed exactly where the chorus stood at the time of the recording (i.e. in the configuration of Tallis’ original intent), in accordance with the location of the individual as well as the partitioned groups; thereby existing as a solid attempt to replicate, for a live audience, the occurrence of being encompassed by a group of live performers (MacDonald 61).

Utilizing the natural acoustics of the room in which she installs her work, Cardiff is attempting to merge reality with art, to blur the line between truth and its imagined interpretation. Her work is not merely a statement to be observed, but a subconscious encounter questioning what we perceive and the ways in which we interact, in company and in solitude. In the context of a museum, the Motet can dissolve the “formal experience – couples shuffling past great works, art students peering in to read wall labels … as visitors cluster in the center of [a] room, letting sound wash over them …, the sudden sound of forty singing voices arriving as an unusually potent balm” (Berwick 1). Listeners are left with an intensely strong perception that they have beheld a live chorus –that they have stood within it and were involved in a true performance. Such an intense reaction partially stems from the inclusion of spatial flexibility: standing ten feet from one’s original location, in any direction, will harbor a minutely (or in some instances, dramatically) altered sensation of sounds. The closer a particular loudspeaker is to a listener, the more a particular performer is detected. A low cough emitted from one source, a sharp exhale from another.

Such manipulation of the mind via auditory device, an “undermining [of] perceptual certainty,” is the elemental ingredient to Cardiff’s work (Lilienthal 101). Motet may be her first major installation of speakers, but the basic concept has resonated in a multitude of her earlier pieces. Her “audio walks,” for example, which require real-time interactions with particular environments, whether they be in museums or parks or underground tunnels, insist on influencing the listener. The sound of a location is recorded, and from there, an audience of one, traversing the very same ground and listening to the recording through a pair of headphones, is “encouraged to synchronize [his or her] footsteps and breathing with [a bodiless guide] as … attention to the landscape … confirm[s] the experience of the immediate surroundings,” flawlessly intermixing invention and reality (Gagnon 261). Along the way, the guide, with the supplement of various natural and recorded sounds, stimulates the imagination, puzzling together a loose narrative structure to the journey. With a deep fixation on film and story-telling, Cardiff regularly applies conventions of Hollywood, not as an ironic or deconstructive gesture, but in an effort to ease the process of “generating wide-awake illusion,” to transition the participant into a personally developed pseudo-reality (Lilienthal 102).

Efficiently constructing this pseudo-reality through sound in Cardiff’s work is facilitated via depth perspective; this is accomplished through a procedure referred to as binaural recording. Admittedly an old technique (it has been studied since 1881), it requires the usage of microphones resembling human ears and their application to a dummy head. The sounds recorded into the microphones are picked up in a fashion approximating the pickup pattern of real human ears; artificial pinnae first perceive the sounds and their spatial relationships to the dummy head, then send the information to be recorded. When relayed on headphones, the recording maintains the relationship of the hearer to the subject of the recording, in effect replicating the original psychoacoustic interaction.

While not a new discovery, binaural recording is certainly retaining popularity (search “Virtual Barber” on the web), and Janet Cardiff has successfully applied this older technology to her work by way of an innovative and intriguing approach. Ghost Machine, a particular example of an audio walk, is an interactive construction set in an empty pay theater. The participant, also equipped with a video camera, is ushered throughout the theater, sometimes by Cardiff herself as she directs him or her to “spot” certain images with the camera and even zoom in on items and people of singular interest. The first half of the walk is an exploration of a man dragging an unconscious woman into the darkness. Who he is is not explained, only questioned. Through these interactions, a visual and aural discussion of the thriller genre also comes into play, delving into the subject of what we as an audience hear and how we perceive it primarily due to our previous encounters with classic film conventions (Lilienthal 101). This is worth the effort, for the implementation of such conventions is allowing Cardiff to greatly reduce the bridge between two very disparate forms of art.

Certainly, the replacement of a conventional theater with an open-air walk through the woods, with the participant not only witnessing fictional events but partaking in them as well, sounds somewhat refreshing; and if the design were to be adapted even more towards traditional cinematic storytelling, there is a very strong chance it could dramatically heighten its popularity – not to mention the fact that it would replace hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of equipment with a common pair of headphones.

Though binaural recording or a forty-speaker installation (in another case, ninety-eight!) is not always practical or affordable, it is undeniably engaging. When such technology is utilized, the overall response is assuredly of a positive nature, but a necessary question to be raised is, “Is the story really becoming more effective?” An audience’s goal is to escape their lives, to free themselves from their own burdens and reach another environment, or another world. In order for this goal to reach fruition, there must be a solid and unbreakable bond to the story being told. As it so happens, by moving [well recorded] space around the listener, “live ambient sound [can] become virtually indistinguishable from [a] recorded soundtrack, producing a weirdly thrilling uncertainty concerning what is fiction and what is ‘recorded reality’” (Weber

53). The audience must be transfixed, and the most efficient means of accomplishing such a feat is to present an aural surrounding of massive detail and interest. The story in and of itself provides much of this; though, as has been discovered over the past century, the way the story is brought to an audience matters very much as well.

With this vital information in mind, techniques such as binaural recording and 10.2

Surround Sound begin to appear more than appropriate as tools to be utilized in transporting an audience member directly into the illusory world of cinematic make-believe. The intent of successfully offering a false reality as truth is a task requiring multiple elements, and in the advancement of sound as storytelling device, technological artists such as Tom Holman have mastered certain realms (such as resolution) while concurrently working on others (notably spatial differentiation); even as more “artistic” technological artists have been applying these advancements in separate yet distantly related fields, as has Janet Cardiff with her interior installations and binaural audio walks. The hope is to eventually forge a flawless recreation of what audiences deem reality (or at least what they can be convinced to believe to be reality), and it appears as though, through our advancing, there is more than one way to approach such an objective. Perhaps in the future, as developments continue to materialize, these distinct paths will more fully merge and work together, employing the benefits of each to the highest potential; or maybe an entirely new solution will be discovered. Regardless, taking into account what is known at this current moment, it must be agreed that man’s previous accomplishments with sound are more than impressive; their goals more than ambitious.

Works Cited

Berwick, Carly. “Forty Harmonious Voices Drown Out Your Woes: Cardiff at MoMA.”

Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.com. 10 Jan. 2006. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

.

DellaSala, Gene; “Introducting the 10/2 Surround Format;” Audioholics; Audioholics, 24

Sep. 2006; Web; 2 Nov. 2009. fig. 1. .

Gagnon, Monika Kin. “Janet Cardiff.” Senses & Society. 2.2 (2007) : 259-264. Print.

Holman, Tomlinson. Personal interview. 20 Oct. 2009.

Holman Tomlinson. Sound for Film and Television. Burlington: Focal Press, 1997. Print. Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller; n.p., n.d.; Web; 2 Nov. 2009. fig. 2.

.

Lilienthal, Matthias. “Playing Roulette with Reality.” The Secret Hotel. Schneider,

Eckhard. Berlin: Kunsthaus, 2005. 100-103. Print.

MacDonald, Corina. “Scoring the Work: Documenting Practice and Performance in

Variable Media Art.” LEONARDO. 42.1 (2007) : 59-64. Print.

Ponnekanti Rosemary. “Embedded in a 40-Voice Choir.” News Tribune 7 July 2008.

Print.

Weber. John S. “Janet Cardiff.” 01101. Coerver, Chad. Canada: San Francisco Museum of

Modern Art. 2001. 52-53. Print.

Leave a Reply