Kurt Vonnegut seemed to like the story of Cinderella. He alluded to it often. I submit that he went so far as to write his own version. He called it Slaughterhouse-Five.

My claim may well be preposterous. Slaughterhouse-Five is not shiny or moralistic like fairy tales. It breaks most of the rules of narrative that fairy tales, particularly Cinderella, rigidly follow. Yet there it is, spelled out unequivocally: “Billy Pilgrim was Cinderella, and Cinderella was Billy Pilgrim” (145). Not much time has been spent properly unpacking that sentence, which to me is the most maddening of the whole book. In fact, it is often inappropriately trivialized, or simply avoided, in many critical circles. Is that sentence everything—the comprehension of which will suddenly prove the final puzzle piece in making sense of this most perplexing of books—or is it nothing? We like to skip over it because it makes no immediate sense and is not tangibly important to the plot. Except, it is important and must not be skipped over. So it is the purpose of the present paper to explain that sentence as best I can. If we expand Vonnegut’s equation of Billy Pilgrim and Cinderella, we may convincingly prove that Vonnegut, perhaps consciously, had Cinderella somewhere in mind when he conceived of Billy’s story. There is no single version of the story of Cinderella on which to base this comparison; our current bedtime version is surely a combination of several, primarily Charles Perrault’s centuries-old Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper (which is the one we know best, thanks to Walt Disney’s uncharacteristically faithful adaptation) and the Grimm brothers’ bleaker retelling.[1] Perhaps not surprisingly, similarities crop up everywhere, if only we take the time to look. Admittedly, this exercise may feel slightly mechanical, but I will make it a point to do more than merely compare. It is possible, for example, that the king’s ball, to which Cinderella is sent in a pumpkin-turned-carriage, is relocated to Tralfamadore in Slaughterhouse-Five—but what does that relocation mean? This is, in fact, not the only possible reading, or even the best. The ball could also be Dresden before the firestorm, or after. Each reading has its own merits and implications. Finally, it is necessary to speculate on Vonnegut’s reasons for invoking, somewhat paradoxically, a classic fairy tale—whose morality is crystal clear—in a seemingly moral-less wartime story. It has partly to do with the nature of fairy tales, which got their start in the oral tradition, and partly to do with the tragic failure of fairy tales to work their magic in certain circumstances. It is no accident that Vonnegut begins Billy’s story, which he repeatedly calls a “tale,” with the injunction to “listen.” This is not a story written for readers, but a tale told for listeners. Let us do some listening now. Vonnegut has a lot to say.

For Vonnegut, it seems the story of Cinderella is the essential fairy tale—“the most popular story ever told,” he says—whose mythic structure has informed a whole history of storytelling. Cinderella’s story is not particular, but universal, which gets us to Vonnegut’s most radical point: Slaughterhouse-Five is Billy’s story as much as it is Cinderella’s—which is why Vonnegut does not stop at saying “Billy Pilgrim was Cinderella.” He makes the converse also true: “and Cinderella was Billy Pilgrim.” This point is of paramount importance and should be restated: Billy and Cinderella are the same person—but, at the same time, neither of them are real people. They are essentializations, simplifications, prototypes, archetypes, common denominators, stories in their most basic form, residers of our collective consciousness. Slaughterhouse-Five is more than a simple retelling of Cinderella; it purports to be a retelling of story. Vonnegut is, as ever, subversive; he comes off, in the first chapter, as aloof, and unhappy with “this lousy little book” (2). He radically downplays its importance but later tries to elevate it to the level of myth—an almost undetectable maneuver. This is not pretension or self-aggrandizement; it is honesty. Any story worth telling is, in some sense, the same story. Cinderella, we might say, does not exist in one time or one space; she, like Billy, exists in the past, present, and future—incidentally (or not), in a very Tralfamadorian notion of time. In his foreword to Anne Sexton’s Translations, Vonnegut says, in that characteristic “for the heck of it” style, of Cinderella, that “She became infinitely happy forever—which includes now” (ix). Cinderella was always happy, will always be happy. I think it no accident, in light of this, that Tralfamadorians see time all at once. For them, Cinderella and Billy exist simultaneously. This is Vonnegut commenting on the timelessness of stories; they can be said to exist outside time, extra-temporally. That is why Billy Pilgrim is Cinderella and Cinderella is Billy Pilgrim, and that is why we can safely proceed with comparing their two stories. But make no mistake: although the story of Cinderella and Slaughterhouse-Five are similar, they are not the same. Vonnegut is merely alerting us to the root of storytelling, from which springs an infinite number of variations.

Vonnegut reimagines the story of Cinderella as postwar and postmodern (the implications of which will be examined later), but retains certain specific conventions and iconographies of the Cinderella story.[2] Well before Vonnegut bluntly states that Billy is Cinderella, he sneakily foreshadows it. From Perrault’s version, we know that Cinderella got her name from sleeping by the chimney corner, where she became covered in cinders. When Billy first enters the banquet hall where the British will perform a musical version of Cinderella for a pathetic, ragtag bunch of American soldiers, he “catches fire, having stood too close to the glowing stove. The hem of his little coat was burning” (96–97). Like Cinderella, his clothes are charred. Clothes are particularly important: both Billy and Cinderella wear outfits embarrassingly unfit for their positions. Billy is a soldier, but he is given a much-too-small fur coat and ridiculed; Cinderella is the beautiful daughter of an honorable man, but she is given rags to wear and also ridiculed. For both, clothes are external representations of their internal insecurity: neither is where he or she should be, and it plainly shows. At the same time, their clothes reinforce that demoralizing insecurity in a vicious cycle. Yet the bulk of the similarities are not with characterization (Cinderella has a much better work ethic than Billy) but with setup and plot.

We know that Cinderella has two evil stepsisters, hell-bent on perpetuating Cinderella’s misery. This is one of the easiest comparisons to make: Billy’s evil stepbrothers are Roland Weary and Paul Lazzaro. The comparison is even more valid when we notice Vonnegut’s repeated references to the failed brotherhood of the American soldiers. Cinderella’s relationship to her two stepsisters is clearly an example of failed sisterhood. For Vonnegut’s purposes, women become men, but family roles do not change. Weary and Lazzaro, who establish a brotherly alliance against Billy, are both puffed-up, rotten men; they feed off each other’s deluded self-importance. Neither shows kindness to Billy, whom they think pathetic and putrid. Like Cinderella’s sisters, they call him names, curse at him, and oppress him out of some sadistic sense of superiority. To extend the importance of clothes, particularly shoes, there is one incident in which Weary’s “hinged clogs were transforming his feet into blood puddings” (64). It recalls a well-known scene from the Grimm’s’ version of Cinderella where the stepsisters slice off chunks of their feet in order to fit into Cinderella’s slippers, bloodying the slippers and their stockings in the process. The similarity may be merely coincidental, but it illustrates nonetheless the psychosomatic dangers of ill-fitting clothing.

Other characters are harder to plot, but nonetheless cannot be overlooked. Billy’s fairy godmother could be Kilgore Trout, whose inspiration takes him to new, fantastical places. Trout never leaves Billy. If we take Billy’s abduction by the Tralfamadorians to be merely a projection of his insane mind,[3] Trout, who wrote an eerily similar book, can be said to have waved his wand and facilitated that projection. But who is Billy’s princess? Valencia Merble, Montana Wildhack, or something much darker than either of those two more literal readings? First, we must determine what event represents Billy’s coming-out party, the equivalent of the king’s ball in the Cinderella story. There are a few possibilities.

First, and perhaps most obviously, is the possibility that Billy Pilgrim’s stay at the zoo on Tralfamadore is akin to the king’s ball, at which he meets his one and only soul mate. In nearly every version of Cinderella, all are taken aback by Cinderella’s matchless beauty: “Everyone stopped dancing, and the violins ceased to play, so entranced was everyone with the singular beauties of the unknown newcomer” (Perrault). It is her moment. She is the star. On Tralfamadore, Billy is likewise the star. The Tralfamadorians think him beautiful: “Most Tralfamadorians had no way of knowing Billy’s body and face were not beautiful. They supposed that he was a splendid specimen. This had a pleasant effect on Billy, who began to enjoy his body for the first time” (113). Both Billy and Cinderella can finally appreciate their own beauty. They have arrived, as it were. If we concede that Tralfamadore is the ball, then we must say Montana Wildhack is Billy’s princess, and there is evidence for that. He seems to care for her, enjoys sleeping with her, and has a child by her—but is she his soul mate, his Princess Charming? As with every relationship in Billy’s life, there is a lack of deep connection, a sense of detachment. When Montana asks for a story, Billy’s responses are monosyllabic and unexciting. But if Montana is not Billy’s princess, certainly it cannot be Valencia, whom he simply tolerates and thinks their relationship only bearable. That is not the language of love.Valencia does bring Billy great wealth, as a princess might, but still we are unsatisfied.

The problem is in the relocation of the ball: might it actually not be Tralfamadore, per se, but rather its earthly counterpart, Dresden? That, in my view, is the stronger reading. It is no accident that Billy’s spaceship ride to Tralfamadore parallels his train ride to the POW camp from which he is sent to Dresden. Dresden is even more of a coming-out party for Billy than Tralfamadore. Consider his arrival: “So out of the gate of the railroad yard and into the streets of Dresden marched the light opera. Billy Pilgrim was the star. He led the parade. Thousands of people were on the sidewalks, going home from work” (150). For the first time, Billy is a leader of men (even if those men are “ridiculous creatures”), and he is “enchanted” by what he sees before him (150). Dresden, like the king’s ballroom, is ornate and beautiful: “The skyline was intricate and voluptuous and enchanted and absurd. It looked like a Sunday school picture of Heaven to Billy Pilgrim” (148). Once again, the word “enchanted” is used. Vonnegut, never a redundant wordsmith, is enshrouding Dresden in fairy-tale wonder, much as he did earlier with the room in which the British perform Cinderella (with words like “witches’ cauldron” and “majesty” [96]). Billy and the men “pranced, staggered and reeled to the gate of the Dresden slaughterhouse” (152). They are dancing, like the king’s guests in Cinderella’s story. Dresden is their ballroom floor, and everyone is watching Billy, but not because he is the most beautiful. In his hilarious getup, Billy is the most absurd: “He had silver boots now, and a muff, and a piece of azure curtain which he wore like a toga” (147). Those silver boots, of course, were Cinderella’s glass slippers in the British soldiers’ play, and they fit Billy perfectly. Unlike on Tralfamadore, where Billy is naked (surely Billy’s subconscious rejection of the oppressive evils of clothing), in Dresden, Billy has been made over, much as Cinderella is made over for the ball. Note Vonnegut’s explanation of Billy’s outfit: “It was Fate, of course, which had costumed him—Fate, and a feeble will to survive” (151). Cinderella, it might be said, is also costumed by Fate, who in her story is personified by a fairy godmother. She, like Billy, strides into a beautiful new place in new shoes, magically bestowed upon her bare feet, and everyone stares. We cannot miss the parallel. Of course, this is only her first arrival at the ball and Billy’s first arrival at Dresden. Both take two trips. Cinderella’s second trip, like Billy’s, is the more substantial; the prince decides then that he must marry her. That is the height of her happiness. Billy’s second trip, after the first storm, and, not surprisingly, in a horse-drawn wagon (except these horses are hurt, and the wagon looks like a coffin, not a pumpkin) is similarly happy. For the first and only time in his life, Billy finds happiness—but in a beloved person? Who is his princess in Dresden? We should rephrase the question: Whom has Billy been courting this whole book? I think the answer is Death (hence the subtitle, A Duty-Dance with Death, again invoking dancing), but then, it is not so much her he wants, but what she offers: escape. He finds that at Dresden. Sun-bathing in the wagon, “He was happy. He was warm” (194). It is the happiest moment of his life.

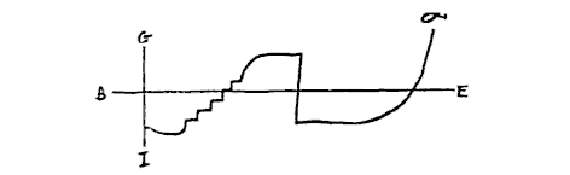

Of course, not all is rosy, as Billy soon discovers when he observes the horses’ bleeding mouths and broken hooves: this is not Cinderella’s happily-ever-after. As said earlier, Slaughterhouse-Five is Cinderella recast in postwar and postmodern colors. We might call it a pessimistic re-mythologization of the Cinderella story. Birds have the last words in both Vonnegut’s story and in the Grimm’s’ version, but whereas Vonnegut’s birds cannot be comprehended, the Grimm’s’ pigeons call out optimistically. However, there should be no expectation of a tonal shift toward optimism in Vonnegut. His experimental narrative is not based on rising and falling action; it is remarkably flat. Take a look at how Vonnegut famously diagrammed Cinderella’s story, which he drew for Sexton (Translations viii):

He writes: “‘G’ was good fortune. ‘I’ was ill fortune. ‘B’ was beginning. ‘E’ was end” (ix). But if he were to diagram Billy’s story, it would mostly be a flat line. Vonnegut rejects the ups and downs of classic narratives; that is the core of his reimaging of Cinderella, a very postmodern strategy, and surely a response to the war, which seemed to suck the extremes out of life. Billy rarely feels. On Tralfamadore, Billy asks the Tralfamadorians “if there wasn’t, please, some other reading matter around” other than “the same ups and downs over and over again” (88). He cannot take extremes, as he learns when he must suffer through the quartet’s songs at his party and breaks down. Billy’s story is still Cinderella’s, but stripped of extremes, a flattening out of emotion. It is sad, but wholly appropriate. There are no princesses in wars. Vonnegut is almost literal here: the German dog employed during the post-battle mop-up, scared and shivering on the battlefield, is named Princess.

The flattening out of narrative structures and de-emotionalization leads inevitably to a purposeful blurring of conventional fairy tale morality, to the point where it becomes inefficacious. As mentioned earlier, fairy tales originated in oral folklore, which Vonnegut invokes by asking us to listen to Billy’s tale. It is a tale Vonnegut has “survived to tell” (my emphasis). Except, he strips it of a clear morality, which is at the core of fairy tales like Cinderella. Perrault even spells out both morals explicitly at the end of his short story. Vonnegut does nothing of the sort. He is reinterpreting a moral story within an amoral setting. Slaughterhouse-Five is an anti-war book; morality cannot possibly exist there. War is not, contrary to certain of his critics, rendered immoral. Rather, it is rendered amoral, which is far worse. At least with immorality, there is morality, for we have the wisdom to tell the difference. With amorality, there is nothing. It reduces men and women to empty shells. More than that, it reduces fairy tales to empty shells. Here is the book’s most frightening implication: war has the power to block even fairy tales from working their magic of optimism. They cannot work; stories, the bedrock of culture, cannot work. War obliterates culture. Poo-tee-weet, Vonnegut’s last word on the subject, means nothing; it implies a complete failure of language. Right when the morality of a fairy tale should crystallize in the end, it collapses into tragic nothingness. Everywhere else the fairy tale story is there: Billy has two evil stepbrothers, both of whom he overshadows at the ball; he is aided by preternatural help, in the form both of Kilgore Trout and of the creatures Trout’s imagination creates in Billy’s mind; Billy courts Princess Death, and wins her peace, if only for a time; and Billy’s feet fit the slippers perfectly. Still, none of it feels like a fairy tale, because stripped of extremes, it cannot. Vonnegut sets it up as a piece of oral folklore from the first word; he wants it to be mythical, to be imbued with that sense of timelessness inherent in the best of fairy tales. But despite his efforts, despite even the blatant equation of Billy Pilgrim and Cinderella, so that there can be no mistaking Vonnegut’s mythological substructure, the fairy tale, mightiest and oldest of stories, cannot hold up against the catastrophic force of war.

Kurt Vonnegut would probably object to the present exercise, maybe even to our conclusion. He thought it “criminal to explain works of art,” which was why he quit teaching (Transformations x). Certainly, it is with a certain pretension that one hazards an explanation of a work of art, however modest his intentions for doing so. Who are we to say what the artist is “really doing”? Did Vonnegut set out to write an anti-war book that implies the very worst: that even our stories, and, by extension, the cultures on which those stories are built, have not the slightest power to stand up against all-numbing war? Did he mean to suggest that the amorality of war, much worse than the immorality of war, is colossally dehumanizing? Did he intend even to write a story structurally similar to the story of Cinderella, or was his invocation of the fairy tale merely comical, some characteristic clownery to diffuse a momentarily overwhelming sense of world-weariness? We obviously will never know what Vonnegut intended, but that is beside the point. I am putting forth merely a possibility that I find provocative. How could I not when he writes sentences like “Billy Pilgrim was Cinderella and Cinderella was Billy Pilgrim”? That by itself—maddening in its elegant symmetry—piques curiosity and invites extensive interpretation. It would be criminal not to explain it. Billy Pilgrim is figuratively rechristened Cinderella; Cinderella is rechristened Billy Pilgrim. It is the center of the novel, but it is not a moment of optimism. It is the saddest conclusion of the whole book. If Billy Pilgrim truly is Cinderella, what a colossal failure for fairy tales! But then, Vonnegut knows we cannot write intelligibly of massacres, because there is nothing to say. Not even fairy tales can penetrate the lunar emptiness.

Works Cited

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. Cinderella. Trans. D. L. Ashliman. Berlin, 1812. Cinderella. 7 Dec.

2009 <http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0510a.html#perrault>.

Perrault, Charles. Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper. Trans. Andrew Lang. Longmans:

London, 1889. Cinderella.7 Dec. 2009

<http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/type0510a.html#perrault>.

Vonnegut, Kurt. Foreword. Transformations. By Anne Sexton.New York: Houghton Mifflin,

1999.

—. Slaughterhouse-Five.New York: Random House, 1969.

[1] Neither Perrault nor the Brothers Grimm wrote in English (Perrault was French, and they German). I have chosen two translations that are both in the public domain—they can both be accessed online without the anachronistic swipe of a library card.

[2] My focus here, however, is not to prove how Billy is one of the thousand faces of the archetypal hero—others are no doubt more adept at deconstructing mythic structures, and it is my insight merely to say that Vonnegut thinks Billy’s story exemplifies those structures—but rather to map Cinderella’s story onto Billy’s (and vice versa). It should suffice to point out, vaguely, that these are classic fish-out-of-water protagonists who undertake some heroic journey, during which they confront their worst fears, enter into metaphorical caves wherein they battle metaphorical monsters, conquer those fears (invariably with help from otherworldly sources, whether Blue Fairy Godmothers or Tralfamadorians), and emerge fundamentally changed. This is the classic story, of which Cinderella and Slaughterhouse-Five are variations. As I said, further study of their classic mythic structures is not relevant here, for I am concerned primarily with how these two stories complement and speak to one another. How else is Billy Pilgrim Cinderella, and what do those similarities imply? Now begins a few minutes of point-by-point comparison.

[3] A view I share, for reasons well-documented and psychoanalytically persuasive.

Leave a Reply