A 2008 Royal Caribbean commercial dares the consumer to “cast off conventions of life on land and set sail, free to ask, ‘Why not?’ Why not ice skate on the equator? Sunbathe past glaciers? Climb mountains at sea? […] Or do nothing at all?” Royal Caribbean’s ships are like giant playgrounds at sea for adults and children alike. As the commercial proudly points out, many ships are equipped with ice skating rinks and rock climbing walls, so there is never an idle moment—unless it is precisely an idle moment a passenger is looking for, of course. Cruise companies market luxury, excess, and an escape from everyday life, which has paid off in a big way. In 2009, the international cruise industry will bring in an estimated $24.9 billion in revenue, serving approximately 16 million passengers worldwide. The number of passengers has grown an average of 7.4% each year since 1990, and this upward trend has shown no indication of subsiding. Though these figures represent the “global” cruise industry, an overwhelming majority of passengers come from the United States, Canada, or Western Europe. In fact, people from these areas generate 86% of the industry’s revenues (CruiseMarketWatch.com). But this does not mean that one cannot find plenty of people from poorer, developing countries on a ship. One would just have to look at the waiters in the restaurant or the workers below deck in the engine room to see a quite different demographic from the target passenger market.

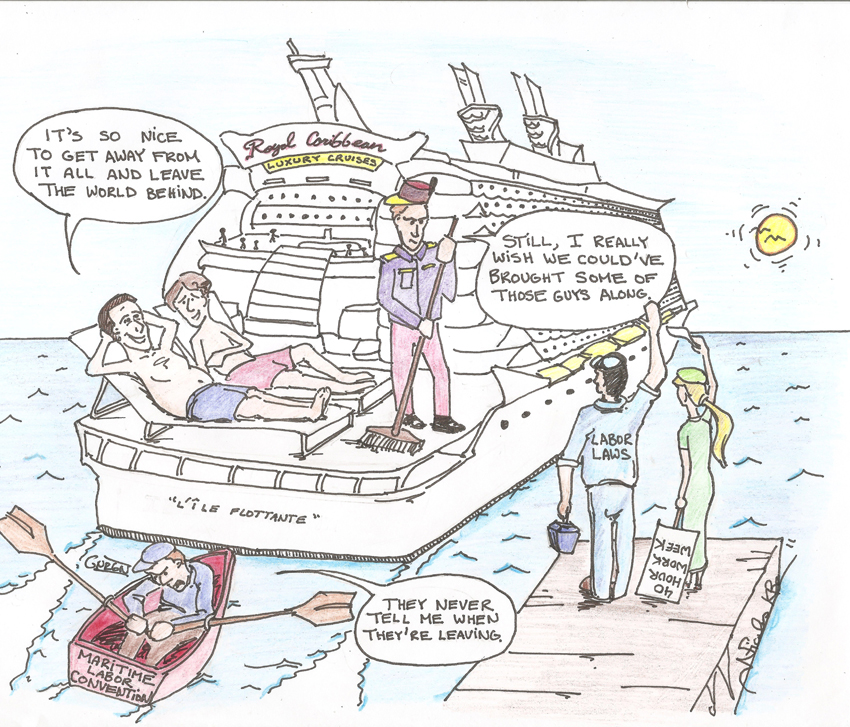

This dichotomy between the rich, Western customers and the workers from developing countries who serve them points to a facet of the cruise industry that Royal Caribbean would certainly not want to feature in its advertising campaigns. Since cruise ships operate in international waterways, outside the traditional boundaries of sovereign states, regulation is difficult and often poorly defined. The result is that, when ships are out at sea, they are basically responsible for policing themselves. Royal Caribbean even alludes to this feature of the industry in its commercial, asking passengers to “declare [their] independence. Become a citizen of our nation.” Though Royal Caribbean uses “our nation” as a tongue-in-cheek marketing ploy, it ironically highlights the very real lack of regulation and accountability in the cruise industry. Ships practically serve as their own sovereign nations when at sea. And, just as land-bound nations have been known to be corrupt and to abuse labor and human rights, cruise ships are prone to the same kinds of violations.

Though ships may act like independent, unregulated actors, they are at least nominally subject to state controls. Cruise ships fall under the jurisdiction of whatever state they are registered in and must obey that state’s laws. However, the problem lies in the fact that companies are allowed to register their ships in whatever country they choose. For this reason, though most cruise companies are American or European owned, the companies choose to register in countries other than the country of ownership. In the cruise industry, the most popular places to register ships are Liberia, the Bahamas, and Panama (International Transport Workers’ Federation, 2000, pg. 3). Thus, Royal Caribbean ships, which are mostly registered in the Bahamas, must only comply with Bahamian laws. They do this because the standards regarding labor are much less stringent in the Bahamas than they are in the United States or Western Europe. So Royal Caribbean uses the Bahamas as a so-called “flag of convenience” to avoid the accountability that registering in the United States, its home country, would bring. The International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) states that companies are motivated to register in places like the Bahamas because of the weak “ability and willingness of the flag state to enforce international minimum social standards on its vessels, including respect for basic human and trade union rights” (ITFglobal.org). In fact, Liberian International Ship and Corporate Registry (LISCR), an American corporation that oversees ship registration in Liberia, uses Liberia’s scanty labor protections as a selling point to encourage ships to register there. The corporation’s website claims that registering in countries other than Liberia that have stricter laws may lead to “higher wages, inflated labour costs and overheads, excessive bureaucracy, and the potential for interference from organized labour” (LISCR.com).

Hiding behind these flags of convenience makes regulation of cruise ships difficult. Regulating ships’ actions is already hard enough given that they operate at sea, far outside traditional law-enforcement jurisdictions. Yet, this problem is compounded by the fact that the states that have the most responsibility to hold ships accountable—their flag states—are purposely chosen to be states less likely to enforce existing conventions. And since Royal Caribbean is not a signatory of the UN Global Compact, while, at the same time, tending to hire its workers from developing countries, the threat of labor violations is high.

Labor Rights

Assessing labor rights on the high seas is difficult because no reporting mechanism exists. Cruise ships are only answerable to the labor laws of the country they are registered in, and these laws are often deficient. In addition, the enforcement of laws, collective bargaining agreements, and international resolutions, such as the 2006 Maritime Labor Convention, poses a practicality problem. As an industry that exists outside conventional state borders with individual units traversing the massive international waterways, it is difficult to police cruise ships. Furthermore, monitoring cruise ships is not typically priority, especially not in countries where most of the ships are registered. Thus, unfortunately, what is known about labor policies in cruise ships mainly comes from firsthand accounts from employees in the industry or from watchdog groups, such as the ITF, that have conducted independent investigations.

The main piece of international legislation outlining the rights of seafarers is the International Labor Organization’s Maritime Labor Convention (MLC). Since its creation in 2006, the three main ship registry countries, Liberia, the Bahamas, and Panama, have ratified the convention, ostensibly agreeing to enforce it. The MLC sets limits on the number of hours cruise ship employees can work: “maximum hours of work shall not exceed: (i) 14 hours in any 24-hour period; and (ii) 72 hours in any seven-day period” (Maritime Labor Convention). The convention further demands that “hours of rest may be divided into no more than two periods, one of which shall be at least six hours in length, and the interval between consecutive periods of rest shall not exceed 14 hours” (Maritime Labor Convention). These hour limits are significantly higher than limits in other industries. In the United States, for example, the workweek for employees covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act is capped at 40 hours. A worker is eligible to receive overtime pay for any hours worked beyond the allowed 40 (U.S. Department of Labor). In the MLC, not only is the hour limit 55% higher than in the United States, but there is no provision for overtime. Yet, even with these permissibly long hours, investigation into labor practices on cruise ships has revealed that the MLC guidelines are often violated.

Violations of the MLC are so widespread that they are often written into a worker’s contract itself. The ITF’s Standard Collective Agreement, which is used as a basis for most contracts in the industry, allows for a maximum workweek of 91 hours (ITF, 2008, pg. 5). This is 19 hours longer than the workweek stipulated by the MLC. A study of Royal Caribbean and Carnival ships by the ITF in 2001 revealed that “almost one-third of crew members indicated they worked 12 or more consecutive hours without a rest period. One-third reported having no rest period longer than six hours. […] Only 25 percent reported having ten hours of uninterrupted rest” (Klein 122). On top of these long hours, most cruise ship employees can expect to work seven days a week without a day off for the duration of their contracts, which can be as long as 10 months. The ITF reports that more than 95% of employees work seven days a week (War On Want and ITF 15). These hours certainly seem excessive by Western standards, but even compared to norms in developing countries where many of the workers are from, the cruise ship hours are still longer. For example, an audit of Nike factories in Vietnam during their sweatshop scandal of the 1990s found that employees worked an average of 10.5 hours a day, six days a week (Vogel 79). The labor practices in these Nike factories, pejoratively dubbed “sweatshops,” caused a public outcry and boycott of Nike products in Western countries. Yet, no such uprising has occurred against the cruise ship industry where the normal workweek is anywhere from seven to twenty-eight hours longer than the workweek in these recognized sweatshops.

The outcry against Nike not only took into account the long working hours, but also the extremely low wages paid to workers. Perhaps the lack of concern for labor rights on cruise ships stems from the fact that, although the employees work long hours, they are paid more than the $1.67 a day Nike’s Vietnamese employees received (Vogel 79). Wages on cruise ship vary based on the type of job. For non-tipping, unskilled positions, such as deckhand or hostess, workers are normally paid between $1000 and $2000 a month (CruiseLineJobs.com). This may seem like a marginally fair amount by comparison, but one has to consider that employees work seven days and up to 91 hours in one week, so the hourly wage is still incredibly low. For employees that are expected to receive tips from passengers, such as dining room waiters, wages are negligible. For example, on Celebrity Cruise Line, a subsidiary of Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd., waiters only receive $50 a month (Klein 130). By even the conservative estimate of a 30-day month made up of 10-hour workdays, this divides out to about 17 cents an hour. Celebrity Cruises says the wage is fair because the rest of the worker’s salary is comprised of passenger tips, which it recommends be $3.50 a day per passenger (CruiseCompare.com). If every passenger were to follow this guideline, a waiter could make around $2500 per month. This rate gives a more favorable hourly wage of $6 to $8, depending on the numbers of hours worked. Yet, if passengers do not tip appropriately, as the case may often be, waiter salaries will be significantly lower than this estimate. To make up for tipping discrepancies, Royal Caribbean claims to compensate waiters if they do not receive a certain base level of tips, but it does not disclose what this base level is (RoyalCaribbean.com). In fact, the only thing Royal Caribbean does disclose about its wages is that they are “competitive with the maritime industry and […] typically provide [employees] with greater financial opportunity than they would receive in their home countries” (Lee, 2006). This abstract statement is typical of Royal Caribbean’s close-lipped treatment of its labor policies.

While these wages are somewhat higher than the pittance paid in third world sweatshops, cruise employees must make sacrifices specific to the cruise ship industry, which may offset the benefits of the extra cash. First, there is the psychological cost of cruise ship employment. A ten-month contract without a day off followed by two months of vacation is the typical work pattern for semi-skilled and unskilled workers employed on ships. Being isolated from one’s family for such a long period of time can take an emotional toll on employees. In addition to these emotional costs, workers often have to pay a substantial amount of money out of pocket in order to procure employment on a cruise ship. An L.A. Times article revealed that “workers frequently have to pay for training, pre-employment physical exams, plane tickets to and from their ships, and recruiters’ fees” (Reynolds and Weikel) before they begin work on the ship. Until very recently, working through a recruiter to get a job on a cruise ship was a widespread practice. Recruiters would serve as a middleman between the corporation and the potential employee by setting up interviews, communicating job offers, and more—all for a price, of course. In one case heard in Miami, ten employees of an undisclosed cruise line swore in court to having paid up to $1300 in recruiters’ fees to secure employment on a ship. Shortly after beginning work, before they could recoup their sizeable investment, the employees were fired and had to take the recruiters’ fees as personal financial losses (Reynolds and Weikel). Though $1300 is a figure on the higher end of the spectrum, workers did commonly have to pay recruiters between $300 and $600, with no guarantee of employment attached. This practice is in direct violation of an ILO mandate, which prohibits agents from collecting money from workers and stipulates that any fees incurred are supposed to be paid by the employer (Klein 128). Thankfully, due to some high profile press and lawsuits, like the Miami case outlined above, the use of these exploitative recruiters has been mostly phased out in the cruise ship industry.

Though the removal of recruiters is a step in the right direction, employees still have to pay considerable sums before they ever set foot on a ship. It is a de facto industry standard to require workers to pay for their roundtrip airfare to and from the ship’s port of call. Since many of these workers are flying internationally—from developing countries in Latin America, Eastern Europe, and Asia—these flights can be very expensive (War on Want and ITF 16). In addition to paying for airfare, workers may also have to pay for their uniforms and other items they will use on the job. The ITF Standard Collective Agreement, as well as the ILO, technically bar these types of costs to employees, which can add up to thousands of dollars (ITF, 2008, pg. 11). Yet, so far there has been no notable change in the practice. This fee structure puts employees in debt before they even begin work, which effectively makes them indentured workers. Although cruise ship employees are not indebted to the companies themselves, like traditional indentured workers, the money they earn on the ship goes toward paying back debts they incurred to obtain the job in the first place. It may take an employee a few months of work to even break even from their original costs. Furthermore, since employees have to invest so much to get employment on a cruise ship and these investments are non-refundable, workers may be less likely to complain about poor working conditions. The fear of losing their job, and, thus, the ability to recoup their investment, keeps many workers silently compliant (Klein 129).

Given how difficult it is for employees to speak out against unfair treatment, it would seem logical that unions would step in to give workers the voices they lack. Yet, unionization has proved to be a particularly thorny issue in the cruise industry. The most famous case of cruise ship collective bargaining gone awry occurred on a Carnival ship. In 1981, 240 Carnival employees went on strike aboard a ship “to protest the firings of two coworkers. The striking ended quickly when Carnival called US Immigration, declared the strikers illegal immigrants, bused them to the airport, and flew them home” (Klein 123). This type of response to collective action is not an isolated incident; similar occurrences have been recorded throughout the cruise industry. Workers have little incentive to fight for their rights if they know they will just be fired for it and shipped home. It is especially easy to get rid of striking employees given that they are required to pre-purchase their own ticket home, as documented above. Thus, the cruise lines suffer no penalties from dealing with strikes in this unjust fashion. For them, it is a win-win situation: they get rid of the striking workers, which will probably save them money, and they do not have to pay anything to do so.

In addition to the threat of job loss, the very structure of the cruise ship work force discourages collective action. Royal Caribbean purposely tries to build crews made up of many nationalities. The company knows that workers from different countries who speak different languages are less likely to come together to try and form a union. Russell Nansen, a former Royal Caribbean training officer, was not shy about his company’s policy. In an ITF report, he stated, “‘If you had too many [workers] of any one nationality, you might have a problem with unions. A few years ago, all the Italian waiters walked off a ship in St. Thomas. The ship didn’t sail for a while’” (War on Want and ITF 13). This so-called “divide-and-rule” strategy seems to have worked for Royal Caribbean, as none of its ships are currently unionized.

Since collective action is difficult, at best, some former Royal Caribbean employees have turned to the United States’ courts for help. In 2000, a group of about 5000 Royal Caribbean employees attempted to sue the company for $55 million in unpaid overtime wages. According to their contracts, employees were only supposed to work 70 hours a week. If employees worked more than the 70-hour limit—which, as previously documented, was the norm rather than the exception—Royal Caribbean was required by contract to pay them higher, overtime wages for the excess hours. And yet, although “evidence showed that these seamen typically worked well over ten hours per day, seven days a week, therefore qualifying most workers to receive special overtime compensation […Royal Caribbean] allegedly failed to pay as promised” (Lee, 2006). The employees also argued that Royal Caribbean officials would often falsify timesheets to make it look like they did not qualify for overtime. In the end, the case came down to a game of “he said/she said” because there was no way to prove what actually occurred on the ship. Yet again, the cruise corporations came out on top because of a lack of external monitoring of ship labor practices. Royal Caribbean ended up settling the case outside of court for $5.3 million, significantly less than what was allegedly owed (Lee, 2006).

Conclusion

Unfortunately, besides this compensatory settlement in 2000, the vague and contradictory conventions governing ship labor practices have rarely been brought to bear in a court of law. The result has been a lack of public awareness and concern for the labor violations in the industry, and accordingly, Royal Caribbean has done little to improve its labor practices. However, precisely because it is clear that Royal Caribbean will only voluntarily improve its practices when the risk of public protest is high, it should be equally clear that voluntary regulation alone is not sufficient to adequately police the cruise industry. If the international history of labor rights abuses provides any sort of testament, it should provides us with evidence that when corporate social responsibility is left to self-regulation, there is much less that the international community can do to monitor and prevent sweatshop conditions.

And yet, it remains that the primary reason that regulation of cruise ships consists of self-regulation comes down to the use of flags of convenience for ship registry. Companies purposely choose to register in countries that less stringently enforce existing laws. Therefore, in the few instances that ships have actually been caught and held accountable, it has usually been because these infractions were committed in another country’s waterway – this was the case when Royal Caribbean was caught polluting U.S. waters in 1999. The problem is that while water owned by a specific country only extends a few miles offshore, most of the world is covered by international water. So, to increase enforcement, it is necessary that, when in international waterways, any signatory country should be allowed to prosecute the ship for violating international conventions.

Such a change would greatly increase the reach and effectiveness of the treaties currently governing the industry. Subjecting ships to the stipulations of international conventions would allow existing laws to be more effectively enforced and it would make it much easier to prevent or at the very least amend many of the labor rights problems outlined in this paper. Even Royal Caribbean would finally be forced to take the initiative to improve its practices. Then, when Royal Caribbean announces in its commercial to be the nation of “why not?”, the international community would be able to respond with something more concrete and forceful than its usual, ineffective response: “because we said so.”

Works Cited

“Celebrity Cruises Information.” CruiseCompare.com. 14 Nov. 2009

<http://www.cruisecompare.com/cruise-information/celebrity-cruises-information.htm>.

“Cruise Job Descriptions.” Cruise Ship Jobs. 2000-2009. 14 Nov. 2009

<http://www.cruiselinesjobs.com/eng/cruise-ship-job-descriptions/>.

CruiseMarketWatch.com. Ed. Ryan Wahlstrom. 2009. 14 Nov. 2009

<http://www.cruisemarketwatch.com/blog1/>.

Fishman, Charles. “One Big Problem- ‘Save the Waves.’” Fast Company Feb. 2000. 7 Nov.

2009 <http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/32/waves.html>.

“Flags of Convenience Campaign.” International Transport Workers’ Federation. 6 Nov. 2009

<http://www.itfglobal.org/flags-convenience/sub-page.cfm>.

International Maritime Organization. International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution

from Ships. London, 1973. 30 Oct. 2009 <http://www.imo.org/Conventions/contents.asp?doc_id=678&topic_id=258#1>.

International Transport Workers’ Federation. The Cruise Industry. Report for The

International Commission on Shipping, Sept. 2000.

—. ITF Standard Collective Agreement. 1 Jan. 2008.

International Labor Organization. Maritime Labor Convention. Geneva, 2006. 6 Nov. 2009

<http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C186>.

Klein, Ross. Cruise Ship Blues: The Underside of the Cruise Industry. Gabriola Island, Canada:

New Society Publishers, 2002.

—. “Pollution and Environmental Violations and Fines, 1992 – 2009.” CruiseJunkie.com.

2009. 7 Nov. 2009 <http://www.cruisejunkie.com/envirofines.html>.

Kulkarni, Neesha and Marcie Keever. “Congress Begins Push to Stop Cruise Industry from

Dumping Sewage.” Friends of the Earth. 21 Oct. 2009. 30 Oct. 2009

<http://www.foe.org/congress-begins-push-stop-cruise-industry-dumping-sewage>.

Lee, Susan. “Cruise Industry Liens Against the U.S. Wage Penalty Act.” Tulane Maritime Law

Journal 31.1 (2006): 141-160.

“The Nation of Why Not.” Youtube.com. 15 Nov. 2008. Royal Caribbean Cruises, Ltd.

14 Nov. 2009 <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22IVCxqsoEU&feature=player_embedded>.

“Points to Compare.” Liberian Registry. 2009. Liberian International Ship and Corporate

Registry. 30 Oct. 2009 <http://www.liscr.com/liscr/AboutUs/AboutLiberianRegistry/

PointstoCompare/tabid/214/Default.aspx>.

Reynolds, Christopher and Dan Weikel. “For Cruise Ship Workers, Voyages Are no Vacations.”

Los Angeles Times 30 May 2000. Reprint in Global Policy Forum. 2009. 14 Nov. 2009 <http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/219/46725.html>.

Rothenberg, Eric and Robert Nickson. “Latest Developments in International Maritime

Environmental Regulation.” Tulane Maritime Law Journal 33.1 (2008): 137-164.

Royal Caribbean. 2008 Stewardship Report. Miami: Royal Caribbean, 2008.

RoyalCaribbean.com. 2009. Royal Caribbean International. 30 Oct. 2009

<http://www.royalcaribbean.com/>.

Skrzycki, Cindy. “Tide Surges Against Cruise Industry’s Wastewater Disposal.” Washington

Post 2 Aug. 2005. 30 Oct. 2009 <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/

2005/08/02/AR2005080200637.html>.

United States. Environmental Protection Agency. “Department of Justice announced that Royal

Caribbean Cruises Ltd. has agreed to pay a $18 million criminal fine.” EPA News Release. 21 July 1999. EPA. 7 Nov. 2009 <http://yosemite.epa.gov/opa/admpress.nsf/

b1ab9f485b098972852562e7004dc686/d4cf84427956628e852567b50070ccaf?OpenDocument>.

Vogel, David. The Market of Virtue: The Potential and Limits of Corporate Social

Responsibility. Washington: Brookings Press, 2005

“Wage and Hour Division.” United States Department of Labor. 14 Nov. 2009

<http://www.dol.gov/whd/flsa/index.htm>.

War on Want and International Transport Workers’ Federation. Sweatships. London: War on

Want, 2001. Downloaded 6 Nov. 2009 <http://www.waronwant.org/sweatships>.

Leave a Reply