ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

From Berkeley, CA, Sonya Egoian is a junior double-majoring in Political Science and Narrative with a minor in French.

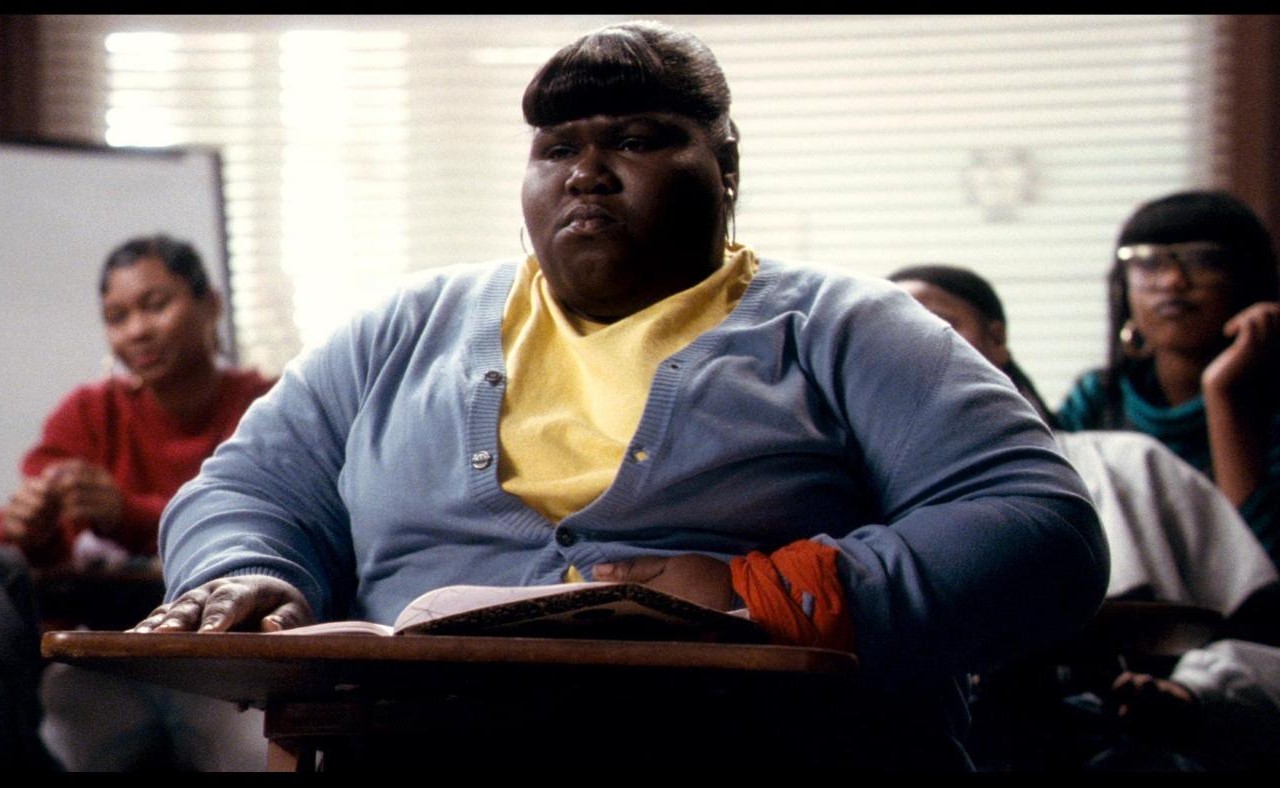

Illiterate, obese, and pregnant for the second time, sixteen-year-old Claireece ‘Precious’ Jones in Sapphire’s gritty novel Push embodies the shortcomings of her Harlem community. Precious lives in utter poverty, receives no support from her school or her home, and suffers harrowing sexual and psychological abuse at the hands of her parents, all of which have made her daily survival both a priority and a struggle. Perhaps most disheartening to Precious is that those around her see her as incapable and averse to learning. As a result, resignation and apathy saturate her classroom experience. Although Precious’ virtual invisibility presents a major obstacle, it does not ultimately imprison her. Precious’ pursuit of art and education serve as avenues of freedom. Push follows Precious as she enrolls in an alternative school, and her boundless creativity and gradually improving literacy release her from the constrictive cycle of poverty and violence.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Precious’ experience exemplifies the Hegelian interpretation that art and education are the saving graces from existence. Though far from the conventional Enlightenment subject, Precious undergoes a journey that explores her imagination and education, eventually liberating her from her reality. A paradigm of the Hegelian ideal of art and knowledge as vehicles of enlightenment, the power of literature that Precious uncovers frees her from her oppressive social conditions. Even though the conclusion of Push reveals that Precious will forever be grappling with the traumas of her childhood, at its core, Push contemporizes the classic philosophy of art as transcendence that empowers its young protagonist.

Precious’ experience exemplifies the Hegelian interpretation that art and education are the saving graces from existence.

Contextually, however, identifying a link between G.W.F. Hegel and Push raises valid concerns. Foremost, as an African-American female, Precious is hardly Hegel’s envisioned philosophical subject. Hegel’s conviction of African inferiority is quite explicit in The Philosophy of History, as Hegel writes that “the Negro [. . .] exhibits man in his completely wild and untamed state” and his characterization of Africa as “the Unhistorical, Undeveloped Spirit” is cringe-worthy at best (111, 117). Hegel viewed enlightenment as accessible exclusively to white, land-owning, and affluent males—those with the means and resources to cultivate an upper-class education. Not only is Precious exempt from all the above criteria, but also implicit in a Hegelian interpretation of Push is the notion that liberation from social oppression is contingent upon a cultured education and appreciation for art. Naturally, those on the periphery of society often face insurmountable odds preventing them from an adequate education. This is cyclically problematic, as the abject poor and uneducated require an education to escape from poverty, and yet their poverty is an obstacle to that objective. This depiction of liberation, then, appears elitist. Since Hegel’s spiritual transcendence is open only to those with the perceived capacity to achieve it, Precious should be barred from liberation given her race, class, and educational background.

Racial politics aside, Hegel’s views on art and education offer a unique insight into Push. By the novel’s conclusion, Precious’ newfound ability to read broadens her horizons and potential, bringing her out of her past and current existence. No longer barred from art by illiteracy, Precious can identify with literature and strive for the higher ideals they represent, an experience that Hegel would call the key to liberation from reality. After Precious is exposed to the works of Alice Walker and Langston Hughes, Precious recognizes art as transcendent to reality; she begins to model her own aspirations after the ideals that surface in her readings. Precious writes that The Color Purple “gives [her] so much strength” and the “fairy-tale ending” of the novel gives her the tools to envision a life outside of her own (Sapphire 82).

Precious recognizes abstract ideals and values, whereas previously she was buried in the material elements of reality. Icons like Hughes and Walker offer Precious “a palpable sense of identity,” as book reviewer Gayle Pemberton notes in her critique of Push (3). Pemberton explains that literacy grants Precious access to authors who understand and empower her. Precious’ empowerment is further emphasized in a moment of epiphany when she attaches meaning to her daily life: “I was born for a purpose [. . .] I know I got a purpose, a reason” (Sapphire 75). Here, the reader sees Precious parting from her previous toughened, cold view that she exists only to serve her mother or feed her child, both which are grounded in concrete acts. Instead, the education that Precious absorbs teaches her to value her life in a new, enlightened way. This aligns with Hegel’s description of the role of art and education in his lectures on aesthetics: “Art by means of its representations, while remaining within the sensuous sphere, liberates man at the same time from the power of sensuousness” (49). Hegel articulates that a true understanding of art frees the viewer or reader from physicality, composed of corporal desires and necessities.

“Art lifts him with gentle hands out of and above imprisonment in nature.”

Despite Hegel’s deplorable racial politics, Precious spiritually embodies his sentiment, as even her brief introduction to narrative art functions as an opportunity for conscious reflection. Unfortunately, Precious’ contraction of HIV at the end of Push prevents her from a wholly Hegelian liberation from reality. Her dire medical and economic conditions pose serious limitations on a full, unbridled freedom. Yet, art does prompt her to elevate herself, which is manifest in her determination to pursue higher education. Precious views art as the key to escaping poverty, akin to Hegel’s description of art as the savior of man: “Art lifts him with gentle hands out of and above imprisonment in nature” (Hegel 49). With her ongoing poetry and journal entries, Precious, too, creates art that both belongs to her world and “lifts” her out of it. She develops an inner, reflective life that frees her from her external reality.

Precious’ escape into enlightenment is mirrored in the transition of her thought content from the material to the abstract. Despite the heavy presence of necessity in her life, Precious’ concerns at the end of the novel are no longer grounded in materiality. During Precious’ first days at her alternative school, she has difficulty accepting her instructor’s more philosophical, moralistic lessons because her thoughts are preoccupied by physical needs: “Miz Rain say values determine how we live much as money do. I say Miz Rain stupid there [. . .] Wait for check, check; cry when check late. Check important [. . .] Don’t tell me ‘bout check not important” (Sapphire 64). Finances are integral to Precious’ life, and her emphasis of the welfare check overshadows Ms. Rain’s attempts to impress a system of values and ethics upon her. Moreover, Precious is apathetic, even reluctant, to engage Ms. Rain in a dialogue about values and ideas. She fails to understand the relevance of values in her life. Toward the end of the novel, however, there is marked change in Precious’ thoughts, which turn primarily to love and the future: “Maybe I never find love [. . .] Wat it be like to bee in luv. I wondr” (Sapphire 95, 102). Words like “maybe” and “wonder” show that Precious begins to engage her curiosity and ask reflexive questions about her future.

Perhaps more importantly, she explores her identity and society’s perception of her: “I always thought I was someone different on the inside. I always thought I was just fat and black and ugly to people on the OUTSIDE. And if they could see inside me they would see something lovely” (Sapphire 125). Her later thoughts are deeper and multidimensional. Her ‘new’ thoughts distinguish her internal identity from the image she projects to others as she examines her relationship with society at large, evidenced through her pronounced use of “inside” and “outside.” Furthermore, she expresses distinct self-worth, a sentiment entirely absent from the first half of the novel. Precious’ heightened awareness again finds parallel with Hegel, as he believes man capable of “lift[ing] himself to eternal ideas, to a realm of thought and freedom [. . .] he strips the world of its enlivened and flowering reality and dissolves it into abstractions” (54). Here, Hegel clearly equates thought to freedom, treating the two ideals as flowing freely into one another. Hegel describes reality as “flowering” and overclouded with superfluities, preventing man from truly understanding ideas and expression.

Perhaps more importantly, she explores her identity and society’s perception of her: “I always thought I was someone different on the inside. I always thought I was just fat and black and ugly to people on the OUTSIDE. And if they could see inside me they would see something lovely” (Sapphire 125). Her later thoughts are deeper and multidimensional. Her ‘new’ thoughts distinguish her internal identity from the image she projects to others as she examines her relationship with society at large, evidenced through her pronounced use of “inside” and “outside.” Furthermore, she expresses distinct self-worth, a sentiment entirely absent from the first half of the novel. Precious’ heightened awareness again finds parallel with Hegel, as he believes man capable of “lift[ing] himself to eternal ideas, to a realm of thought and freedom [. . .] he strips the world of its enlivened and flowering reality and dissolves it into abstractions” (54). Here, Hegel clearly equates thought to freedom, treating the two ideals as flowing freely into one another. Hegel describes reality as “flowering” and overclouded with superfluities, preventing man from truly understanding ideas and expression.

A contemporary of Hegel, Friedrich Schiller more specifically addresses the issue of aesthetic education as revelatory: “Man, when he reflects, can conceive of Virtue, Truth, Happiness [ . .] those abstractions [. . .] that is the business of physical and moral education” (113). Schiller posits virtue, truth, and happiness as inaccessible to man without the aid of education, and in the rest of his letters on aesthetics he ascribes a uniting quality to education. Like Hegel, Schiller sees man as strapped to sensuality in spite of his efforts, and the purpose of education is to marry man’s sensuous and ideal-driven spheres: “When both these aptitudes are conjoined, man will combine the greatest fullness of existence with the highest autonomy and freedom” (Schiller 88). Schiller’s freedom is the harmony of physical learning and intense concentration on abstractions and feeling. The union of the individual with his state gives rise to freedom. This is uniquely manifest in Push, as Precious’ education liberates her from what Hegel calls the “bad, transitory world” while simultaneously creating a space for her in society (9). Pemberton concisely synthesizes this creation of Precious’ personal and societal identity: “Precious seeks to find herself through reading, and then she creates herself through language” (Pemberton 3). Pemberton aligns with Schiller, seeing knowledge as harmonizing an individual’s spirit with his role in society. Amidst the turmoil of her external reality, Precious finds an inner balance that helps her to emerge from her social conditions.

“Man, when he reflects, can conceive of Virtue, Truth, Happiness [ . .] those abstractions [. . .] that is the business of physical and moral education.”

The transition in the fabric of Precious’ thoughts is also paired with a progression in her narrative structure that exhibits a nuanced understanding of literature and the discovery of liberation through art. In Precious’ early journal entries, her writing is fragmented and minimal, understandably so because writing is unfamiliar and somewhat demoralizing for her. Moreover, the quality of her earliest entries is limited in scope to factual and superficial elements: I gt babe agn Babe bi my favr (I got baby again Babe by my father) (Sapphire 69). Her writing reflects her existence: restricted and anchored to reality. However, as Push nears its conclusion, Precious develops her own narrative style and a penchant for poetry. Furthermore, her poems probe deeply into her emotional and psychological condition and they become more philosophical in nature. The first stanza of the poem that Precious writes after learning she has contracted HIV from her father is particularly emblematic of the artistic expression she has cultivated:

For

A monf it bin like this. I feel daze.

Ms Rain see it

say you not same girl I know.

is tru. I am a difrent

persn

anybuddy wood be don’t u think?

dont

u

think. (Sapphire 99)

Precious harnesses poetry to grapple with her life-altering diagnosis, as her poems allow her to articulate her thoughts and vent her emotions. Her unusual poetic structure exhibits a confidence and trust in her writing that was absent in her prior entries. Although her tone seems sad and confused in the first half of the stanza, it becomes accusatory toward the end as she nearly challenges the audience to disagree that anyone would be irrevocably changed in her situation. As vulnerability gradually replaces her hardened exterior, the artistic expression that emerges in Precious’ later writings affords her a near therapeutic freedom to articulate and cope with her emotions through poetry.

The vulnerability gives way to confidence as Precious becomes self-empowered through literacy. She reinvents her identity, represented by her critical decision to steal and read her administrative file. As Precious seizes control over her literacy, she can read her file with minimal assistance, yet she is dismayed to find that her history of abuse has been included and that her counselor suggests she become a home attendant. These facts, and the file in general, symbolize the way that others in society have viewed Precious throughout her life, and she describes her file as a dark, enigmatic presence that administrators spoke of but that she had never understood. Quite literally, Precious’ decision to read her file is akin to Precious ‘reading’ herself for the first time. Precious’ ability not only to “read the whole thing by [her] self” but also to critique it demonstrates the agency and enfranchisement she discovers (Sapphire 123). She rejects the identity that her turbulent past has sculpted, as well as the various labels society has confined her to in her file, like “disappointing” and “abused” (Sapphire 118, 120). While Precious is upset at the file’s categorization of her past, she displays an unparalleled anger at its seeming predetermination of her future, further demonstrating her growing confidence. The file states that Precious “seems to envision social services, AFDC, as taking care of her forever,” and yet Precious screams back at the inanimate file “No way!. . .I’m getting my G.E.D., a job, a place for me and Abdul, then I go to college” (Sapphire 120).

The vulnerability gives way to confidence as Precious becomes self-empowered through literacy. She reinvents her identity, represented by her critical decision to steal and read her administrative file. As Precious seizes control over her literacy, she can read her file with minimal assistance, yet she is dismayed to find that her history of abuse has been included and that her counselor suggests she become a home attendant. These facts, and the file in general, symbolize the way that others in society have viewed Precious throughout her life, and she describes her file as a dark, enigmatic presence that administrators spoke of but that she had never understood. Quite literally, Precious’ decision to read her file is akin to Precious ‘reading’ herself for the first time. Precious’ ability not only to “read the whole thing by [her] self” but also to critique it demonstrates the agency and enfranchisement she discovers (Sapphire 123). She rejects the identity that her turbulent past has sculpted, as well as the various labels society has confined her to in her file, like “disappointing” and “abused” (Sapphire 118, 120). While Precious is upset at the file’s categorization of her past, she displays an unparalleled anger at its seeming predetermination of her future, further demonstrating her growing confidence. The file states that Precious “seems to envision social services, AFDC, as taking care of her forever,” and yet Precious screams back at the inanimate file “No way!. . .I’m getting my G.E.D., a job, a place for me and Abdul, then I go to college” (Sapphire 120).

Clearly, education has allowed Precious to aspire for goals beyond those listed in her file, and she desires to free herself from living with the bare minimum. The author herself states during an interview that, while Precious was “enslaved by her ignorance,” she “finds a way out” through the “acquisition of literacy” (Hoover 1). Sapphire comments that, while she could have written a sudden windfall of money or an upper-class romance into the story line that would also have functioned as escapes from Precious’ reality, “reading and writing. . .put her in control of her own life, as opposed to looking outside of herself to heal her, transform her, accept her, or to love her” (Hoover 1). The author’s statements suggest that it was imperative for Precious to muster an internal strength, independently of other forces. Precious’ choice to read her file, coupled with Sapphire’s interview, reveal that education organically allowed Precious recreate herself.

Precious’ improving literacy certainly helps her to redefine her identity and her future, but the confidence that accompanies it filters into other, more tangible areas of her life. The barriers against vulnerability and dependency begin to crumble. At first reluctant to even pen her feelings in her journal, Precious gradually learns the advantages of seeking support and guidance. Eventually, the journal as an emotional vent escalates to her attendance at an incest support group and her move into a halfway house. These decisions illustrate Precious’ desire to minimize the presence of material dependency in her life, as she is no longer preoccupied with finding food and shelter for her and her child. This graduates to a crowning realization of inner freedom:

Precious’ improving literacy certainly helps her to redefine her identity and her future, but the confidence that accompanies it filters into other, more tangible areas of her life. The barriers against vulnerability and dependency begin to crumble. At first reluctant to even pen her feelings in her journal, Precious gradually learns the advantages of seeking support and guidance. Eventually, the journal as an emotional vent escalates to her attendance at an incest support group and her move into a halfway house. These decisions illustrate Precious’ desire to minimize the presence of material dependency in her life, as she is no longer preoccupied with finding food and shelter for her and her child. This graduates to a crowning realization of inner freedom:

Everything is floating around me now. Like geese from the lake. I see the wings beating beating hear geeses. It’s more birds than geeses. Where so many birds come from. I see flying. Feel flying. Am flying. Far up, but my body down in circle. Precious is bird. (Sapphire 129)

Precious articulates this feeling while hearing another incest victim share her story at the support meeting. She experiences a spiritual liberation, via a revelation of the collective bonds that linked her with a, sadly, large group of women. This is arguably the culminating moment in the novel, as she truly experiences a transcendent moment through her identification with the soaring birds in the sky, an image that captures the essence of freedom.

Precious’ determination to conquer her illiteracy causes social and psychological breakthroughs in her life. She no longer feels chained to her poverty and her personal growth is exponential as she fights back against her oppressors. Certainly, literacy opens a world of knowledge to Precious, but it also allows her to understand self-love, a previously foreign concept to her. Her freedom is a release from material existence, but also the establishment of a connection to the spirituality within herself. Precious’ undeniable realization of the value of art and education, despite the barriers constructed by modern poverty and Hegel’s own biases, lends even more credence to the universal power of education, a power that spans history and culture. In twentieth-century urban Harlem, Precious unearths the seeds of Hegelian thought to achieve the liberation that neither she, nor Hegel, thought possible.

Sources

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. The Philosophy of History. Ontario: Batoche Books, 2001.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art. Oxford: Clarendon, 1998. Print.

Pemberton, Gayle. “A Hunger for Language: Push by Sapphire.” The Women’s Review of Books, Vol. 14, No. 2. (1996): 1-3. Old City Publishing, Inc. Print.

Sapphire. Push: A Novel. New York: Vintage Contemporaries/Vintage, 1997. Print

Sapphire. “Sapphire on Precious’ Emancipation.” Sampsonia Way. By Elizabeth Hoover. Pittsburgh: City of Asylum, 2010. Print.

Schiller, Friedrich. On the Aesthetic Education of Man. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1982. Print.

Leave a Reply