When I was in third grade, my mother went on sabbatical. I was confused as to why, all of a sudden, she was home all the time instead of teaching classes at Davidson College like she normally did. She proceeded to explain to me that she was getting paid time off because she was a tenuredprofessor. With only eight years of life experience (and having been raised around heavy southern accents), I made the only logical assumption that a child hearing the word “ten-yur” for the first time could make: tenure means that you are guaranteed a job at a college for ten years.

I would later learn that this is not, in fact, the definition of the word tenure.

As explained by Patrick Keef, the former dean of faculty and current chair of the Mathematics Department at Whitman College, academic tenure is “a permanent commitment by a college, presuming that a faculty member meets the standards of excellence for the duration of a career.” However, like most millennials these days, it looks like colleges have developed a fear of commitment, because tenure rates have dropped drastically in past decades.

Tenure rates are decreasing?

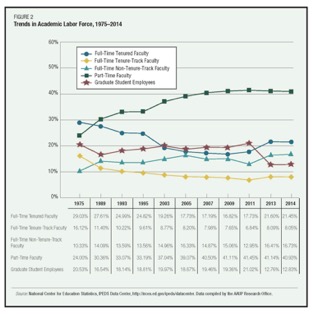

Yes, and at an astounding pace; in 1969, roughly 78 percent of college faculty were tenured or tenure-track, while less than one fourth were on a non-tenure track. By 2009, those percentages had nearly flipped, with only one third of faculty on tenure or tenure-track. In subsequent years, that number has only continued to decline.

Understandably, workforce composition changes with time, and the decrease in tenure-track positions, combined with the recent (and increasingly prevalent) “gig economy” phenomenon of short-term jobs, has expedited job redistribution in many fields. Individuals are less likely to stay with the same career over the course of their adult life, which has manifested itself in academia as the birth of a new class of instructor, including part-time lecturers, adjuncts, full-time lecturers, grad student teaching assistants, visiting professors—the list goes on. As seen in the table below, this collective class of non-tenure-track instructors has comprised the new faculty majority for some time now—In fact, tenure-track faculty haven’t constituted the majority of faculty in the US since the late 1970s—but in recent years, the discrepancy has become extreme.

Source: AAUP Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, 2015-16, Figure 2

What’s the problem?

With this workforce shift, major flaws in our system for higher education employment have become apparent. Of tenure positions that are left, even for schools with higher tenure rates, the positions being awarded do not adequately represent diversity in academia. Though the field has certainly seen diversification from what it used to be, underrepresented minorities and women are disproportionately represented in temporary or non-tenure-track positions; a recent studyfrom the TIAA Institute found that African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans held roughly 13 percent of faculty jobs in 2013, yet they still only hold 10 percent of tenured jobs. Additionally, women hold just 38 percent of tenured jobs despite the fact that they now constitute nearly half of total faculty positions nationwide, and their growth in tenured and tenure-track positions has slowed substantially. As of 2013, fewer than one in ten faculty women received a full professorship—a position that I thought, growing up, was normal for women to have. (It turns out my mother is the exception to the rule.)

Even at a research institution like USC, which has higher rates of tenure than many universities, there are major discrepancies in who is awarded tenure: according to the review of 106 tenure hearingsin USC’s Social Sciences and Humanities departments between 1998 and 2012, 92 percent of white male faculty were awarded tenure, while only 55 percent of female and minority faculty received the same honor. Additionally, in 2016, there were half as many full-time female tenured professorsat USC as there were male tenured professors. The system is majorly biased, and it needs to change.

Should we just get rid of it?

No, not while conditions for non-tenured faculty are so bad—reallybad, actually. According to a UCLA survey of higher education faculty in the 2010-11 school year, less than half of all part-time lecturers reported having access to a shared office space (much less a private one), telephone, or personal computer. Even if non-tenure-track jobs tend to showcase higher rates of faculty diversity than those of the tenured population, they still come with their own set of problems and can pose major difficulties in long-term planning.

With no formal criteria for non-tenure-track faculty recruitment and hiring processes, many colleges hire new faculty within days of the start of the semester. This rushed hiring often results in missed formal institution orientations and barely any prep time for classes. In many cases, non-tenure-track faculty may not receive important department communications or be included in faculty meetings, either. Consequently, they have few opportunities for input on curriculum design, can’t contribute effectively to academic planning, and may not be aware of policy changes affecting their work.

Non-tenure-track faculty can also have their contracts terminated on very short notice, giving them little time to apply elsewhere before the start of a new semester and eliminating the job security that originally made working in education so appealing. To add insult to injury, despite frequently being asked to complete the same tasks as tenured faculty, non-tenure-track faculty still receive substantially smaller paychecks and are usually ineligible for raises or promotions. As a result, between 20 and 30 percent of adjunct professors have to teach at multiple schools to make a living, and many of those who don’t take on additional work struggle to make ends meet: approximately 25 percent of part-time lecturers’ households rely on some form of public assistance from the federal government.

Where is the future of higher education headed?

The trade-off in pursuing a career in education used to be that, even though professorship wasn’t necessarily the most lucrative field, the promise of tenure at least made it a secure one, with enough compensation to get by. However, as colleges and universities are becoming increasingly reliant on non-tenure-track positions to comprise general faculty populations, those old security and monetary incentives are disappearing. These changes are discouraging many people from entering the field in the first place, resulting in the loss of an entire population of individuals with untapped teaching potential.

Aside from the disadvantages that temporary and adjunct positions place on faculty, the increase in dependence upon these positions by universities to make up a majority of faculty has been shown to have a negative effect on students; empirical research from several studiessuggests that colleges’ increased reliance on non-tenure-track faculty has negatively impacted student retention and graduation rates. In fact, a 2009 study found that graduation rates actually declined as proportions of non-tenure-track faculty increased.

It’s no wonder that student learning is negatively impacted when the majority of professors are non-tenure-track. If these professors are constantly being hired within days of the start of the semester and left out of department communications, how could they have adequate time or resources to prepare for their courses? Additionally, part-time faculty are often less accessible to students, which leads to fewer regular faculty members for students to build relationships and interact with. This limited interaction not only restricts the potential scope of understanding and discussion of class material, but can also affect letters of recommendation.

Generally, the blame for these shortcomings in students’ educational experiences is placed on individual faculty members rather than the conditions that they’re constrained to work under. Consider, though, a newly hired adjunct professor not making use of effective new teaching practices. Are we really to believe that they’re purposefullyproviding a subpar education? Or is it more likely that, because they are not receiving regular department communications, they are unaware of new teaching strategies? Or maybe, because their paycheck is so low, they have had to take on second and third jobs that have ended up detracting from their preparation time for classes? Or perhaps their contract is up for review at the end of the semester and they are scared that experimenting with new strategies might negatively affect their teaching evaluations (which, for an adjunct, may make the difference between another year with the university or a letter of termination).

The quality of student learning is suffering, but it isn’t the adjunct’s fault. The culprit here is much larger than any one individual. The culprit here is the system—and we need a system overhaul.

What do we do?

Ideally, universities and institutions would make changes to the tenure system in order to create more accessible and stable career paths for instructors, while incorporating diversity measures in the process. Obviously, this is much easier said than done.

However, vast changes can still be accomplished within our system of higher education employment if we work to ameliorate non-tenure-track faculty conditions—and USC professor Adrianna Kezar is pioneering the way. Kezar is the director of the Rossier School’s Delphi Projectat USC, which tracks faculty hiring changes nationwide and studies contributing factors to national professoriate demographics, with the goals of developing new models of faculty hiring and improving non-tenure-track positions. While shedding light on the negative consequences following the shift away from the tenured faculty workforce, Kezar also remains open to new or alternative workforce models, and reminds us that “one under-discussed reason for the shift away from tenure in the first place was a desire for faculty focused exclusively on teaching, rather than splitting time with research.” Kezar believes that tenure should be re-designed with teachingas the main goal, not research. And in the meantime?

Boards. Institutional boards can mitigate many of the problems with non-tenure-track faculty designs by setting priorities and ensuring that leaders at the institutions address these discrepancies. Boards can raise questions about faculty composition through the commissioning of reports and faculty climate surveys. They can ask administrators to look at budgets and ensure faculty planning follows institutional mission statements (including what type of faculty—i.e., full-time, tenured—best embody those mission statements). They can ask administrators for staffing plan reports and hold them accountable for hiring procedures. And they can support efforts like the Delphi Project that pave the way for reform.

Although utilizing institutional boards is only a small step, it’s somewhere to start. Ultimately, we as a society are as smart as the children we teach and as successful the young minds we shape and prepare for the real world. By creating thriving workplace dynamics and desirable job benefits, we can attract the brightest minds to higher education employment, and, in turn, create the brightest minds through successful course instruction. But if we want to do this, we need to change the path we are on. We need to get educated on our professorial employment system, and give it the remodeling it deserves. We owe it to students and teachers alike to raise our standards for higher education.

—

Via Savage is a senior studying psychology and songwriting at USC. Originally from North Carolina, she grew up with a music professor and an art professor for parents, who instilled in her from a young age a simultaneous passion for education and the arts. Via loves yoga, hiking, and discovering new music, and she plans to pursue a career in the music industry upon graduation.

Leave a Reply