David Chengazhacherril is a junior majoring in Economics and Mathematics with minors in Computer Programming and Business Finance. He is a member of various organizations here on campus including the Applied Statistic Club, Trojan Investing Society, and Corpus Callosum. He is planning on working at PayPal this summer as an intern. In addition to school, he likes to go to the beach and to read. He also enjoys outdoor activities such as swimming and hiking.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

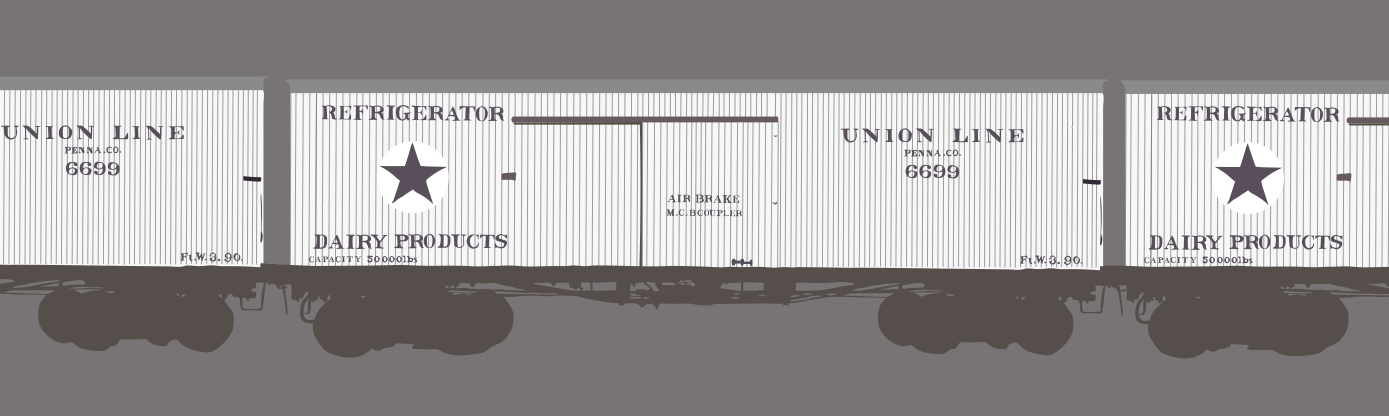

Big Ideas in Small Packaging: The Refrigerated Rail Car’s Redefinition of the Perishable Foods Industry

In the early eighteen-forties, the American meatpacking industry was nothing more than a string of individual butchers spread throughout the country. While the idea of going to a storefront and watching an animal get slaughtered to bring home seems both cruel and barbaric, it was customary in the lives of many citizens throughout the nation. This idea was redefined by railroads, specifically the refrigerated rail car, which nationalized the meatpacking industry and turned most local butchers into merchants of larger corporate meat schematics. The two enormous meatpacking conglomerates, Swift Company and Armour Company, turned the once popular individual butchers into pawns of a national meat producing industry. This led to larger social implications such as the rise of Chicago as a global commercial center and the refrigerator car as the predominating method of transporting perishable foods across the country. The revolution in the meat packing industry spurred by the refrigerated car demonstrates how corporate sponsorship can shape small ideas into long-term social change.

The refrigerated rail car was a highly innovative ‘small’ idea that had limitless potential to redefine the entire meatpacking industry. The traditional process of shipping livestock across the country was not only inefficient in space allocation, but also translated to injury and sickness in animals. Gustavus Swift, a meager butcher’s assistant in Chicago, redefined this entire process with the construction of the first workable refrigerated train car. Simply constructed by lining a standard freight car with ice from Lake Michigan, the makeshift train car was adopted quickly for transporting perishable foods across the country (Besanko 100). Although this idea did not appear to be a groundbreaking revelation, Gustavus Swift’s simple solution had the potential to solve most of the looming problems that existed in transportation of livestock for the meatpacking industry. By lining railcars with ice, Swift could transport carcasses without any undesirable cuts of meat in place of large animals. Soon this budding idea became a fully functioning product when Gustavus Swift hired engineers to fit ice blocks into train ceilings and created the first operational refrigerator car (Bonasia). However, it was not until major corporations took hold of this innovation that the true potential of the refrigerated rail car was realized.

The corporatization of the refrigerated rail car redefined many aspects of the social atmosphere of America. As Gustavus Swift’s invention of the refrigerated rail car grew, so did the Swift and Armour Company which both invested heavily into the refrigerated rail car and achieved new levels of profit (Goldfield 41). As the refrigerator car became the most viable method of transporting perishables across the country, more traditional institutions began to completely disappear from the social eye. While individual Americans were nostalgic to some of the traditional practices that once existed, corporations continued to push social change and turn these older businesses into memories of the past. The Los Angeles Times released an article describing the old milk train and its disappearance as a result of the refrigerated rail car saying, “Americans who want to catch one last glimpse of the vanishing institution are advised to act quickly before the milk train is completely superseded” (REFRIGERATED CARS REPLACE). The refrigerated rail car’s impact on the perishable foods market is only one example of how corporations continued to redefine societal norms in America. New manufactured ideas began to kill off almost all local competition and large companies gained more power in deciding the direction of American industry.

As corporations in the meatpacking industry began to nationalize the market, criticism arose from local butchers who had huge social investments in learning the ‘craft’ that had been marginalized by the redefined atmosphere of the meatpacking industry. Local butchers with years of apprenticeship and home-raised livestock were slow to recognize the new direction of the meatpacking industry. Smaller scale butchers were forced to sell their storefronts because the Armour Company simply undercut most butchers that rebelled against the rail car (Goldfield 41). There was a time when consumers either had to pay the higher prices of local animals or for animals with minor injuries from rail transit; however, as larger corporations began selling cheaper quantities of meat, at similar quality, local butcher shops were unable to keep up. Local economies swapped individuals for corporate entities and large storefronts became the expectation in the everyday sale of meat (Besanko 100). As corporations extended the geographic boundaries of the meat industry far beyond the means of local butchers, nationalized demand for meat grew to oust any market power that local butchers once enjoyed in the meat industry.

Locally produced meats and local butchers were too late to adapt to the unifying powers of the refrigerated rail car and their efforts to acclimate to the new direction of the meat packing industry were hindered by a decreasing market for their product. Local butchers tried to make a selling point of the craftsmanship and quality of labor that went into their product; however, this allure was lost to most people who simply wanted efficient and cheap meats. In Upton Sinclair’s iconic novel, The Jungle, Sinclair gives a vivid description of the corrupt working space that meat was produced in and the complete corporate dominance that meat packing companies enjoyed over their workers lives (Sinclair). Consumers either did not know or did not care that their meat was produced under such radically different and disastrous working conditions. Consumers were only concerned with purchasing cheap and fresh meat which the new meatpacking industry could provide. While local butchers required a term of apprenticeship, the meatpacking industry became an efficient machine swapping in unskilled laborers and throwing them out just as quickly. In practice, most skilled butcheries had to accept the fact that at this period of time there was simply no market for their product. The refrigerated train car’s impact on the meat packing industry brought about Chicago’s transformation from a merchant based economy to a modern corporate industrial economy (Schneirov). The refrigerator car’s simple design and broad implications enhanced the powers of corporations that invested in it and this critical advantage redefined the market for meat production.

The domination of the meatpacking industry was created as a result of a new company developing an innovative technology and gaining a critical advantage over old producers. Although this dominating strategy, pushed social change in the early 19th century, the idea of overtaking old industry standards by harnessing new technologies has modern sensibilities as well. The development of a web-order movie delivery system does not seem like a huge revelation, but the rise to prominence of Netflix is largely a result of this innovation that had not yet been thought of. Blockbuster, a massive movie-supplying conglomerate, did not adapt quickly to the emergence of the web and its unwillingness to adapt to the new market of the Internet led to its ultimate downfall. Netflix used Blockbuster’s unwillingness to adapt to change in order to make their distribution system more efficient. They harnessed a completely innovative and new technology and were able to create a market for web movie rentals that inspired a complete redirection of societal norms.

The idea of effortless streaming, downloading, and receiving movies, was a complete redirection of the DVD-rental market that existed in the realms of Blockbuster’s dominion. It is currently regarded as nearly normal to lie in bed for hours ordering movies online and having them delivered or streamed onto a personal computer, but this idea was completely unheard of in the early 21st century. Corporations are able to shape the social norms that become homogenized in American culture by developing innovations into practical and marketable new technologies. By remaining transfixed on past success, older institutions are ultimately overrun by the new inventions that are constantly being developed. This unwillingness to adapt to new innovation is the ultimate downfall of many corporations. The refrigerator rail car, which set the precedent for new innovation in an entire industry, demonstrated that adapting to new technology is the only way to thrive in a continually changing economy. Corporations have the power to create long-lasting social change by investing in new ideas, but there is equal responsibility to adapt to new ideas and the continual ebb and flow with the innovations of the future.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Works Cited

Besanko, David, David Dranove, and Mark Shanley. Economics of Strategy. New York: Wiley, 2000. Print.

Bonasia, J. (2011, Apr 14). His refrigerated railcars brought home the bacon innovate: Gustavus swift’s cool idea iced a meat empire. Investor’s Business Daily. Print.

Goldfield, David R. Encyclopedia of American Urban History. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2007. Print.

REFRIGERATED CARS REPLACE MILK TRAINS. (1926, Mar 15). Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File). Print.

Sinclair, Upton. The Jungle. Cambridge, MA: R. Bentley, 1971. Print.

Schneirov, R. (1980, Spring). Chicago’s great upheaval of 1877. Chicago History, 9, 2-17. Print.

Leave a Reply